The Bootstrapper's Bible

SECTION 1 | This manifesto is based on The Bootstrapper’s Bible, a book I wrote a few years ago. What I’ve done is divided it into short sections, so you can find the little kernel of insight you need, when you need it. (I hope!)

The Joy of Small

What’s a Bootstrapper?

Well, since you bought this manifesto, chances are that you qualify! For me, a bootstrapper isnʼt a particular demographic or even a certain financial situation. Instead, itʼs a state of mind.

Bootstrappers run billion-dollar companies, nonprofit organizations, and start-ups in their basements. A bootstrapper is determined to build a business that pays for itself every day. In many ways, itʼs easiest to define a bootstrapper by what she isnʼt: a money-raising bureaucrat who specializes in using other peopleʼs money to take big risks in growing a business. Not that thereʼs anything wrong with that…

You can use the information in this manifesto to make any company more focused, more efficient, and more grassroots. Throughout this manifesto, though, Iʼll be primarily addressing the classic bootstrapper: entrepreneurs who are working their butts off to start a great business from scratch with no (or almost no) money.

At last count, there were several million bootstrappers in this country, with another few million wannabes, just waiting for the opportunity. My goal is to give you enough insight and confidence that youʼll get off the bench and make it happen.

The Bootstrapper’s Manifesto

TAPE THIS TO YOUR BATHROOM MIRROR AND READ IT OUT LOUD EVERY NIGHT BEFORE YOU GO TO BED:

am a bootstrapper. I have initiative and insight and guts, but not much money. I will succeed because my efforts and my focus will defeat bigger and better-funded competitors. I am fearless. I keep my focus on growing the business—not on politics, career advancement, or other wasteful distractions.

I will leverage my skills to become the key to every department of my company, yet realize that hiring experts can be the secret to my success. I will be a fervent and intelligent user of technology, to conserve my two most precious assets: time and money.

My secret weapon is knowing how to cut through bureaucracy. My size makes me faster and more nimble than any company could ever be.

I am a laser beam. Opportunities will try to cloud my focus, but I will not waver from my stated goal and plan—until I change it. And I know that plans were made to be changed.

I’m in it for the long haul. Building a business that will last separates me from the opportunist, and is an investment in my brand and my future. Surviving is succeeding, and each day that goes by makes it easier still for me to reach my goals.

I pledge to know more about my field than anyone else. I will read and learn and teach. My greatest asset is the value I can add to my clients through my efforts.

I realize that treating people well on the way up will make it nicer for me on the way back down. I will be scrupulously honest and overt in my dealings, and won’t use my position as a fearless bootstrapper to gain unfair advantage. My reputation will follow me wherever I go, and I will invest in it daily and protect it fiercely.

I am the underdog. I realize that others are rooting for me to succeed, and I will gratefully accept their help when offered. I also understand the power of favors, and will offer them and grant them whenever I can.

I have less to lose than most -- a fact I can turn into a significant competitive advantage.

I am a salesperson. Sooner or later, my income will depend on sales, and those sales can be made only by me, not by an emissary, not by a rep. I will sell by helping others get what they want, by identifying needs and filling them.

I am a guerrilla. I will be persistent, consistent, and willing to invest in the marketing of myself and my business.

I will measure what I do, and won’t lie about it to myself or my spouse. I will set strict financial goals and honestly evaluate my performance. I’ll set limits on time and money and won’t exceed either.

Most of all, I’ll remember that the journey is the reward. I will learn and grow and enjoy every single day.

TRUE STORY 1:

I AM A LASER BEAM

The big call came just a few months after Michael Joaquin Grey and Matthew Brown had started up their toy company. Would the two San Francisco bootstrappers like their product included in the movie marketing blitz for The Lost World? Nope, said Grey and Brown, who preferred to stick with their vision of gradually building a market for Zoob, their plastic DNAlike building toy.

What the bootstrappers feared was a loss of identity. If they hooked up with the celluloid dinosaurs, theyʼd be seen as just another Jurassic spinoff. On their own, they could create a separate brand and not only avoid extinction but create their own world. Eventually, the two even hope to have their own Zoob movies.

TRUE STORY 2:

THE BOOTSTRAPPER IS HERE FOR THE LONG HAUL

Jheri Redding started not one, but four companies. And when the renowned bootstrapper died at 91 in 1998, all four—including the first, Jheri Redding Products, begun in 1956—were still in operation. Howʼd he do it?

Redding created lasting businesses through the combination of a gift for spotting long-term opportunity and his relentless drive to create significant competitive advantages in product features and distribution clout. The Illinois farm boy became a cosmetologist during the Great Depression because he saw hairdressers prospering and farmers failing. He soon began experimenting with shampoo formulas and showed remarkable flair for innovation.

Redding was the first to add vitamins and minerals to shampoos, the first to balance the acidity of the formulas, and the first to urge hairdressers to supplement their haircutting income by selling his products on the slow days of Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. The first? Yes, and also the last. There arenʼt many like Jheri Redding, who also founded Redken (1960), Jhirmack (1976), and Nexxus Products (1979).

TRUE STORY 3:

I WILL KNOW MORE ABOUT MY FIELD THAN ANYONE ELSE

When Yves Chouinard starting scaling mountains, rock climbers used soft cast-iron pitons that had to be discarded after a single use. Chouinard, who was as passionate about climbing peaks as he was about his work as a blacksmith, designed a new piton of aircraft-quality chrome-molybdenum steel. The tougher, reusable piton met climbersʼ needs much better and became an instant success.

As piton sales climbed, Chouinard himself kept climbing too, as much or more than ever. He recalls, “Every time I returned from the mountains, my head was spinning with ideas for improving the carabiners, crampons, ice axes, and other tools of climbing.”

Itʼs been 40 years since the blacksmith-climber hammered out his first steel piton. Since then, it and his many other designs have become the foundation for Patagonia Inc., a $100 million outdoor apparel company based in Ventura, California. Although heʼs now a highly successful businessman, Chouinard still climbs regularly, testing his companyʼs new products while honing its most important tool: his own matchless knowledge of climbersʼ needs.

TRUE STORY 4:

I AM A SALESPERSON

Shereé Thomas had a personal question in mind when she called the customer service line of the company that makes Breathe Right nasal strips. But when she found herself talking to the companyʼs medical director, she went beyond her question and revved up a sales pitch for a liquid she had invented that neutralizes the smell of cigarette smoke on clothes and hair.

A couple of switchboard clicks later, Thomas was on the line with the companyʼs president. And three weeks after that, the company had signed a licensing agreement to invest $4 million to manufacture, market, and distribute Banish, the product Thomas mixed up in her chemist-grandfatherʼs garage. Through the licensing deal, this Cedar Park, Texas, bootstrapper will rack up around six figures in annual royalty payments. Her investment in the sale: a phone call to the companyʼs toll-free line—and a personal commitment never to stop selling.

TRUE STORY 5:

THE JOURNEY IS THE REWARD

Charles Foley was 18 when he told his mother he expected to invent things that would be used everywhere. At 67, the inventor has 130 patents to his credit, including one for the venerable party game Twister, which he invented in the 1960s and still sells today.

But Foley, of Charlotte, North Carolina, is still at the inventing game. He recently revived a discovery of his from the 1960s, an adhesive-removing liquid, and sold the rights to make and market it to a company headed by his son. Heʼs also working on new designs for fishing floats and a home security system.

Driven to search for success? Hardly. Foleyʼs just following his bootstrapping nature on a journey thatʼs lasted a lifetime. “I was born with a gift,” he shrugs. “Ideas pop into my head.”

WHAT’S A BIG COMPANY GOT THAT YOU HAVEN’T GOT?

Most of the companies you deal with every day, read about in the media, or learn about in school are companies with hundreds or thousands of employees. They have an ongoing cash flow and a proven business model. (Iʼll explain what that is in the next chapter.)

Because this is the way youʼve always seen business done, itʼs easy to imagine that the only way to run a business is with secretaries and annual reports and lawyers and fancy offices. Of course, this isnʼt true, but itʼs worth taking a look at the important distinctions between what they do and what you do.

Just as playing table tennis is very different from playing Wimbledon tennis, bootstrapping your own business is a world apart from running IBM. You need to understand the differences, and you need to understand how you can use your size to your advantage.

Traditional companies succeed for a number of reasons, but there are five key leverage points that many of them capitalize on.

1 DISTRIBUTION. How is it that Random House publishes so many best-selling books, or Warner Music so many hit records? Distribution is at the heart of how most businesses that sell to consumers succeed. In a nutshell, if you canʼt get it in the store, it wonʼt sell.

Companies with a lot of different products can afford to hire a lot of salespeople. They can spread their advertising across numerous products and they can offer retailers an efficient way to fill their stores with goods.

Traditional retailers want the companies that sell them products to take risks. They want guarantees that the products will sell. They want national advertising to drive consumers into the store. They insist on co-op money, in which the manufacturer pays them to advertise the product locally.

Thatʼs why Kelloggʼs cereals are consistently at the top of the market share list. Lots of smaller companies can make a better cereal, and they can certainly sell it for less. But Kelloggʼs is willing to pay a bribe (called a “shelving allowance”) to get plenty of space at the supermarket. Kelloggʼs airs commercials during Saturday morning TV shows. And Kelloggʼs has hundreds of sales reps wandering the aisles of grocery stores around the country.

Kelloggʼs wins the market share battle in mass-market cereals because it succeeds at the last and most important step: getting the product in front of the consumer.

2 ACCESS TO CAPITAL. The big guys can borrow money. Lots of it. Itʼs no big deal for a car company to raise $200 million to pay for a new line of cars. In industries where the expenses for machinery, tooling, research and development, and marketing are high, big companies with cheap money often prevail.

Microsoft, for example, took six or more years to turn Windows from a lame excuse of a product into the market-busting operating system it is now. Year after year after year, it lost money marketing lousy versions of Windows. How could it afford to do this? By raising money from the stock market at very low cost and hanging in.

Big companies have access to capital that a little guy canʼt hope to match. A hot company like Yahoo! is able to raise money from the stock market with no personal guarantees, no interest payments, no downside risk. And it can raise a lot. More established companies can issue bonds or get lines of credit for billions of dollars. The banks and investors that back these companies arenʼt looking for a monthly or even a yearly return on their investment. Instead, theyʼre focusing on building profits a decade from now. A bootstrapper could never afford to compete with this approach.

If a market can be bought with cash, a big company will do it.

3 BRAND EQUITY. Why would you be more likely to try a new line of clothes from Nike than from Joeʼs Sporting Goods Store? Because Nike has invested billions of dollars in building a brand name, and youʼve learned to trust that name. Nike can leverage its name when introducing new products.

Donʼt underestimate the power of the brand! Financial World magazine estimates that the Marlboro name and logo are worth more than $2 billion. Any tobacco manufacturer can make a similar cigarette. But only Phillip Morris gets to extract the profit that comes from having more than 50 percent market share.

If the consumer of the product is likely to buy from an established brand name, the big company has a huge advantage.

4 CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIPS. Especially for companies that sell in the business-to-business world, access to customers is a tremendous advantage. Time Warner collects nearly one-third of all the advertising dollars spent on magazines in this country every year.

When Time launches a new magazine, it has a tremendous advantage in selling the ad space. A fledgling competitor, on the other hand, has to start from scratch.

Last year, Costco sold more than $30 million worth of shrimp in its giant warehouse stores. The company can choose from hundreds of different shrimp suppliers (it all comes from the same ocean!), but it deals with only three firms. Why? Because the shrimp buyer at Costco doesnʼt have time to sift through every possible supplier every time she makes a new purchase. So she works with companies she trusts, companies sheʼs worked with before.

In established markets, customer relationships are a huge advantage.

5 GREAT EMPLOYEES. Big companies are filled with turkeys, lifers, incompetents, and political operators. But there, among the bureaucrats, are some exceptional people. Great inventors, designers, marketers, salespeople, customer service wizards, and manufacturers. These great people are drawn to a company that has a great reputation, offers stability, and pays well. Smart companies like Disney leverage these people to the hilt.

During a meeting with someone at Disney, I saw a stack of paper on the corner of his desk. “Whatʼs that?” I asked. He replied that they were resumes. More than 200 of them, all from extraordinarily qualified people, one with a gorgeous watercolor on it. All of them had come from one tiny classified ad in the LA paper. Big companies attract powerfully talented people.

Whatʼs a bootstrapper to do? Big companies have better distribution, access to money whenever itʼs needed, a brand that customers trust, access to the people who buy, and great employees. Theyʼve got lots of competition, big and small, and theyʼve sharpened their axes for battle.

Do you have a chance to succeed?

No.

Not if you try to compete head to head in these five areas. Not if you try to be just like a big company, but smaller. If you try to steal the giantʼs lunch, the giant is likely to eat you for lunch.

Inventing a new computer game and trying to sell it in retail outlets would be crazy— Electronic Arts and Brøderbund will cream you. Introducing a new line of sneakers to compete head to head with Nike at the core of its market would be suicidal.

You have to go where the other guys canʼt. Take advantage of what you have so that you can beat the competition with what they donʼt.

Many bootstrappers miss this lesson. They believe that great ideas and lots of energy will always triumph, so they waste countless dollars and years fighting the bad guys on their own turf.

Thatʼs why the gourmet food business bugs me so much. Every year, another 2,000 gourmet items—jams, jellies, nuts, spreads, chips—are introduced. And every year, 1,900 of them fail. Why? Because the bootstrappers behind them are in love with an idea, not a business. Successful bootstrappers know that just because they can make a product doesnʼt mean they should. Making kettle-fried potato chips from your grandmotherʼs recipe may sound appealing, but that doesnʼt mean that you can grow the idea into a real business.

Given the choice between building a thriving, profitable business with a niche and a really boring product and putting your life savings into an intensely competitive business where youʼre likely to fail but the product is cool, the experienced bootstrapper will pick the former every time. If you find an industry filled with wannabe entrepreneurs with a dollar and a dream, run away and look for something else!

Now letʼs take a look at the good news. You have plenty of things that the big guys donʼt, things that can give you tremendous advantages in launching a new business.

1 NOTHING TO LOSE. This is huge. Your biggest advantage. Big, established companies are in love with old, established ways. They have employees with a huge stake in maintaining the status quo. How many of the great railroad companies got into the airline business? Zero. Even though they could have completely owned this new mode of transport, they were too busy protecting their old turf to grab new turf.

Whenever a market or a technology changes, thereʼs a huge opportunity for new businesses. The number-one Web site on the Internet isnʼt run by Ziff Davis or Microsoft. Itʼs run by an upstart bootstrapper named Jerry Yang (Yahoo!).

Fifteen years ago, I met with Jim Levy. At the time, he was running the fastest-growing company in the history of the world. Activision had exploded on the scene, introducing one videogame after another, capturing a huge share of the Atari 2600 marketplace. After just one year, the company had transformed itself from bootstrapper to fat, happy bureaucracy.

As a freshly minted, slightly arrogant MBA, I decided it was my job to tell him what to do next. So I handed him an article from the Harvard Business Review and explained that he ought to start using some of the huge profits that Activision was earning to take over the brand-new software market. By making software for IBM PC and Apple Macintosh, he could leverage his early lead and his cash and own even more markets.

But Jim had something to lose. His investors and his employees wanted more years like the one theyʼd just finished. They didnʼt want to hear about investing in new markets. They wanted to hear about profits. So Activision did more of the same.

A few years later, they were bought for, like, $4.34.

2 HAPPY WITH SMALL FISH. In the ocean, the first animals to die are the big fish. Thatʼs because they need to eat a lot to be happy. The small guys, the plankton, can make do with crumbs. Same is true with you. Disney canʼt be happy with a movie that earns less than $40 million at the box office. Compare this to the entrepreneur in Vermont who made a kidsʼ video in 1990 called Road Construction Ahead. He was just delighted when he made more than $100,000.

Think about the orders of magnitude at work here: $40 million at the box office is 400 times $100,000. Just imagine all the room there is for a small business that operates under the radar of the giant.

Find a niche, not a nation.

3 PRESEDENTIAL INPUT. In many companies, the president has no trouble getting things done. When Jack Welch at General Electric wanted the ice maker on the new fridge to be quieter, you can bet people in the engineering department paid attention. And when Jack wants to have a meeting with some key customers in Detroit, odds are that theyʼll make time for him—hey, heʼs the president of the whole company.

But in big companies, the president is far removed from the action. GE has tens of thousands of employees and only one Jack Welch. Heʼs surrounded by people with their own agendas. He rarely gets to change the whole company.

The other day, one of my employees flew to Detroit. He had a special fare ticket and knew that his travel options might be restricted, but he got to the airport four hours early for his flight back. Another flight, virtually empty, was leaving in 15 minutes.

Jerry asked if he could fly standby. After all, the plane was flying back to New York anyway, it was empty, and it would cost the airline exactly zero to fly him back now, instead of four hours from now.

The gate agent said no. Do you think the president of the airline would have made the same decision? Do you think he would have wanted a valuable customer to spend four hours seething about the airline when he could have walked right onto a plane? Do you think the president would have wanted to see his valuable brand equity wasted in such a stupid way? I doubt it. But the president wasnʼt there. A gate agent having a bad day was there instead.

You, on the other hand, are the president of your company, and you have a lot of interaction with your customers. You make policy, so youʼll never lose someone over a stupid rule. You can use this power and flexibility to make yourself irresistible to demanding customers.

4 RAPID R&D. They say you canʼt hire nine women to work really hard as a team and produce one baby in one month. Teamwork doesnʼt always make things faster—it can even slow them down.

Engineering studies have shown time and time again that small, focused teams are always faster than big, bureaucratic ones. Obviously, itʼs harder to pick a team of four great people than it is to assign two dozen randomly selected people to a project. And itʼs riskier too. So most companies donʼt do very well when it comes to inventing breakthrough products.

When theyʼve got a problem at IBM, they assign a squadron to it. A squadron that sometimes creates bad ideas, like the PCjr. Barnes & Noble didnʼt invent Amazon.com. One smart guy named Jeff Bezos did. Microsoft and IBM didnʼt invent the supercool Palm Pilot. A much smaller company called US Robotics bought an even smaller company that developed it. Motorola and GE didnʼt invent the modern radar detector. Cincinnati Microwave did.

Big companies will almost always try to reduce invention risk by assigning a bureaucracy. You, on the other hand, can do it yourself. Or hire one person to do it. Thatʼs why you so often see great new ideas come out of tiny companies. Theyʼre faster and more focused.

5 THE UNDERDOG. When Viacom or Microsoft or General Motors comes knocking, lots of smaller companies smell money. They know that the person theyʼre meeting with doesnʼt own the company (that employee might be five or ten levels away from anyone with total profit responsibility) so theyʼre inclined to charge more. After all, they can afford it!

In addition to charging big companies full retail prices, smaller businesses are used to the hassles that big companies present. Purchase orders and layers of bureaucracy. Lawyers and insurance policies and more. So in order to deal with the big guysʼ inherent inefficiencies, they have to plan ahead and build the related costs into their prices when dealing with the Viacoms, Microsofts, and GMs.

Big companies donʼt treat people very well sometimes, and people respond in kind. You, on the other hand, run a small company. So you can acquire the distribution rights to a video series for no money down. Or convince Mel Gibson to appear in your documentary for union scale. Or get your lawyer to work for nothing, for a while, just because youʼre doing good things.

6 LOW OVERHEAD. You work out of your house, with a simple phone system, no business affairs department, very little insurance, no company car, and volunteer labor. If you canʼt make it much more cheaply than the big guys, youʼve either picked the wrong product (hey, donʼt go into the computer chip business!) Or youʼre going about it the wrong way.

Even though big companies are big in scale, they still have to turn a profit on each and every product they sell or pay the consequences sooner or later. The guy whoʼs losing money on every order shipped and trying to make it up in volume is in for a rude awakening.

By leveraging your smallness, you can often undercut bigger competitors, especially if the product or service you create doesnʼt require a lot of fancy machinery.

7 TIME. The big companies donʼt have a lot of freedom in the way they deal with time. When you have to pay off the bankers every month, please the stock market, and grow according to schedule, there isnʼt always the flexibility to do things on the right schedule. Sometimes theyʼve got to rush things, and other times they hold things back.

You, on the other hand, are a stealth marketer. No one is watching you. Sometimes, when it counts, youʼll be ten times faster than the big guys. But when you can make a difference by taking your time, you will—and itʼll show.

A REAL-LIFE EXAMPLE OF TAKING ADVANTAGE OF YOUR SIZE

(Or, how id software completely redefined the computer game market and made millions.)

The software company that calls itself id is a classic bootstrapper. It makes violent computer games that run on home computers. Its software is usually developed by a group of 2 to 10 people, then published by a big company like Electronic Arts. It costs a huge amount to make a new product (sometimes more than a million dollars) but amazingly little to make one more copy (as low as 50 cents).

So the idea in computer game software has always been to spend whatever it takes to make a great game, then spend whatever it takes to get shelf space in the software stores, then hope and pray that you sell a lot of copies. One hit like Myst can pay all of a companyʼs bills for years to come.

Id became famous for a game called Castle Wolfenstein. As an encore, the four guys who founded id decided to follow their own rules in playing against the big companies. They did it with a game called Doom.

They brazenly broke the first rule of software marketing—they gave Doom away to anyone who wanted to download it. Free. Millions of people did. It quickly became the most popular computer game of the year. It didnʼt cost id very much to allow someone to download the game, but the company wasnʼt receiving any income at all.

In stage two, id offered a deluxe version of Doom with more levels, more monsters, more everything. Partnering with a big guy (GT Interactive), it got the software into stores around the country. And sold it directly by mail order.

With a user base of millions of people, id got to call the shots. Instead of being at the mercy of the gatekeepers of distribution, it was courted by distributors and retailers. By inventing a completely different business model, a model in which it had nothing to lose, id redefined a business and won.

Take a look at all the attributes listed in this chapter. Id took advantage of the seven that help the bootstrapper and steadfastly avoided the five that help the big company. By redefining the game and playing on its home field, it trounced companies valued at more than half a billion dollars.

Hereʼs how id used the seven bootstrapper tools:

1 NOTHING TO LOSE. The method used by id threatened to destroy software distribution as we know it. Which was fine with id, but not so fine with the guys at the big software companies. Thereʼs no way in the world they would have had the guts to do this themselves.

2 HAPPY WITH SMALL FISH. Because id didnʼt spend any money on advertising, and because it had developed the game itself, it didnʼt need Doom to be the best-selling computer game of the year to be happy. Even 30,000 sales would have been enough to make the venture successful.

3 PRESIDENTIAL INPUT. Id had total consistency. The game was designed, marketed, licensed, and managed by the same four people. No miscommunication here.

4 RAPID R&D. There were no budget committees, no marketing schedules, no organizational charts to get in the way. (Itʼs interesting to note that it took three times as long for id to create Doomʼs sequel. The gameʼs makers had apparently forgotten what they had learned about rapid R&D.)

5 THE UNDERDOG. Consumers love to root for the hippies at id. It makes them more likely to spread the word and to buy (not copy) the final game.

6 LOW OVERHEAD. Thereʼs no question that high overhead costs would have wiped these guys out.

7 TIME. They knew they could ship when they needed to, instead of when shareholders demanded a new influx of sales. Because they controlled time, they could use it to their advantage.

The flip side of these seven attributes, of course, is what id didn’t do. Here are some ways you can redefine the big guys out of the way on these five attributes:

1 DISTRIBUTION. Never start by selling your product in major stores. Instead, use mail order. Or sell directly to just a few customers for lots of money per sale. Or use the Internet. The last step in your chain is traditional distribution.

2 ACCESS TO CAPITAL. Be cheap. In everything. Donʼt pick a business in which access to money is an important element. That means that building a cable service, a worldwide cellular phone system, or a chemical refinery probably wouldnʼt be on your list. When you do need capital, donʼt pay retail. Borrow from customers or suppliers. Find an equity angel. But donʼt borrow at 18 percent! And donʼt use your personal credit cards.

3 BRAND EQUITY. Position yourself against the brand leader. Be “cheaper than Fritoʼs” or “faster than Federal Express” or “cooler than Leviʼs.” The more the other guyʼs brand gets publicized, the more your positioning statement increases in value. Be brazen in the way you compare yourself to the market leader. Your story should be short, solid, and memorable.

Youʼve probably already seen the Internet analogy. Almost every single dot com failure is due to studied ignorance of the points that lie above. Well-funded Net start-up companies didnʼt act like id. They figured that they had enough money to act like a big company. They were wrong.

4 CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIPS. You donʼt have much of a chance of grabbing a big piece of an established companyʼs business away from one of its good customers right away. Itʼs just too easy for the company to defend against you. Instead, you can try one of these strategies:

• THE INCHWORM. Get a little piece of business as a test. Then, with great service and great products, slowly but surely steal more and more of the big guyʼs business. Focus on one client at a time. By the time the other guy catches on, itʼll be too late.

• SELL TO SOMEONE ELSE. Either to companies that donʼt already have a relationship with your target customer or to someone in a different department at your target customerʼs company— someone who doesnʼt know sheʼs supposed to buy from any particular vendor. This strategy works at home too. For example, Saturn found that by marketing its cars to women, it could grab market share that might have automatically gone to Ford if the car-buying decision for couples had been up to the man.

5 GREAT EMPLOYEES. Not every employee is searching for great reputation, stability, and high pay. Amazingly enough, there are lots of people who would prefer a great adventure, stock options, flextime, a caring boss, a convenient location, or a chance to grow without bureaucracy. By focusing on what you offer that the big guys donʼt, you can capture your own share of greatness.

This manifesto, like most business books, may seem a little intimidating. Itʼs filled with countless things you must do right and countless things that can go wrong.

In fact, you may feel like giving up.

And I can guarantee that if you donʼt feel like giving up today, there will definitely be days when you do feel like giving up. Which brings me to the most important, most concrete, most useful piece of advice in the whole manifesto. Simple, but indispensable: Donʼt give up. Surviving is succeeding. Youʼre smarter than most people who have started their own businesses, and smarter still than those who have succeeded. Itʼs not about what you know or even, in the end, about what you do. Success is persistence. Set realistic expectations. Donʼt give up.

YOU CAN’T WIN IF YOU’RE NOT IN THE GAME.

A lot of this manifesto is about survival. A true bootstrapper worries about survival all the time. Why? Because if you fail, itʼs back to company cubicles, to work you do for someone else until you can get enough scratched together to try again.

Bootstrapping isnʼt always rational. For some of us (like me), itʼs almost an addiction. The excitement and sheer thrill of building something overwhelms the desire to play it safe. This is an manifesto about how to make the odds work in your favor, how to keep playing until you win.

SECTION 2 | A great idea can wipe you out

I started thinking about this manifesto when I heard a public radio report about an American entrepreneur who was busy installing a string of pay phones in Somalia. His biggest expense, the announcer explained, was armed guards to protect the phones. I shook my head. Perhaps the only thing sillier would have been setting up a Pizza Hut franchise in the war zone.

There are enough obstacles to success in choosing your business. Overcoming a flawed business model shouldnʼt be one of them.

You need to start before you start. Figuring out which business to be in is one of the most important things you can do to ensure the success of your new venture, yet itʼs often one of the most poorly thought out decisions bootstrappers make.

Donʼt rush it. Donʼt just pick what you know, or what you used to do, or even what you dreamed of doing when you were a teenager. Itʼs way more fun to run a successful vegetable stand than to be a bankrupt comedy club owner.

The first law of bootstrapping: Great ideas are not required. In fact, a great idea can wipe you out.

Whatʼs a great idea? Something thatʼs never been done before. Something that takes your breath away. Something so bold, so daring, so right, that youʼre certain itʼs worth a bazillion dollars. An idea you need to keep secret.

Great ideas will kill you.

Coming up with a brilliant idea for a business is not nearly as important as finding a business model that works. Whatʼs a business model? This classic MBA phrase describes how you set up a business so you can get money out of it. Below are some sample business models. See if you can guess which company each comes from:

1 HIRE THE WORLD’S BEST ATHLETES AS SPOKESPEOPLE. Buy an enormous amount of advertising. Use the advertising to get every sporting goods store to carry your products. Make your product overseas for very little money. Charge very high prices.

2 FIND LOCAL BUSINESSES THAT CARE ABOUT THEIR EMPLOYEES. Offer them a free water cooler if they allow you to refill it. Earn money by making deliveries on a regular basis.

3 CREATE THE OPERATING SYSTEM that runs every personal computer in the world. Then use the power you gain from knowing that system, which controls the computers, to create software, Web sites, online services, even travel agencies.

Right. These are the business models of Nike, Poland Spring, and Microsoft. What makes these descriptions business models? They are formulas that take the assets of a company and turn them into cash. Without a business model, a company can get publicity, hire employees, and spend money—but it wonʼt make a profit.

In a free society, the government doesnʼt control who gets the right to start a business. Anyone can do it—in most cases without a license, a permit, or a training course. This has one chilling implication: as soon as a business starts to make money, other people will notice, and theyʼll start a business just like it. This is called competition, and it usually keeps people from retiring at the age of 28.

A business model is a machine, a method, a plan for extracting money from a system. Hereʼs another, simpler one: Buy ice cream sandwiches from a wholesaler. Put them in a refrigerated truck, drive them to the nearest beach, and sell them at retail. You make money on every ice cream sandwich you sell! (I did this in high school, by the way. I didnʼt make much money, but I did gain ten pounds.)

At first, this isnʼt such a profitable venture. But then add another layer: Buy cases and cases of ice cream sandwiches from a distributor, put them into 20 trucks, hire high school kids to sell them, and keep half the money. Suddenly, youʼre making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

Go one step further: Buy directly from the manufacturer, at an even lower price. Put your own label on the sandwiches. Then load up 200 trucks. Youʼll need a fleet administrator, insurance policies, and a thousand other things. But youʼve built a business.

At every step along the way, our fictional ice cream magnate made choices. He chose to bypass the supermarket. He chose not to advertise. He chose not to be the cheapest. He chose not to open an international branch. His path shows us all the key elements of a business model:

DISTRIBUTION. Where is it sold to the ultimate consumer? What middlemen are involved?

SALES. Who is selling it for you and how are will they be compensated?

PRICING. What do wholesalers and retailers and consumers pay?

PRODUCTION. How do you make it?

RAW MATERIALS. Where do you get what you sell?

POSITIONING. How do the ultimate users position the product in their minds?

MARKETING. How do consumers find out about it?

BARRIER TO ENTRY. How will you survive when competitors arrive?

SCALABILITY. How do you make it bigger?

GET OFF ON THE RIGHT FOOT BY STARTING THE RIGHT BUSINESS

Understanding the mechanics of a business model is essential before you start your business. Business models should have the following five attributes:

1 THEY SHOULD BE PROFITABLE. Youʼd be surprised at how often people start businesses that lose money on every product and then try to make it up in volume! That lemonade stand you ran when you were seven was a great lesson—you need to make money to stay in business. The only thing is that when youʼre seven, your mom gives you the lemons for free.

Almost no business is profitable on the very first day. The baker has to buy ovens, pay the rent, and purchase ingredients. The consultant needs business cards and brochures. The question is: How long before profitability? Write down a target date. If you go way past it, figure out how to fix the problem or quit. Staying in a losing business because youʼve already lost a lot of money is a bad business strategy. Learn how to detect the factors that change a business from profitable to unprofitable. If youʼre contracted to deliver goods at a fixed rate but your suppliers can raise their prices on you, youʼve just become a very risk-taking middleman.

Thereʼs a great cartoon of a mathematician doing a complicated proof on the blackboard. The board is covered with all sorts of squiggles and symbols and then, at the bottom, it says, “And then a miracle happens,” followed by the end of the proof. Business models canʼt depend on miracles any more than mathematics can. Every once in a while a business comes along that creates its own model. I can tell you that itʼs infinitely better to have one before you start.

Using my favorite ice cream example, the business just doesnʼt work if implicit in the business model is the fact that youʼre going to lose money on every ice cream sandwich and make it up by selling more. This sort of wacked-out thinking only works on the Internet, and even there it wonʼt work for long.

2 THEY SHOULD BE PROTECTIBLE. A profitable business, as mentioned earlier, is going to attract competitors. What are you going to do when they show up? If youʼre accustomed to making $1 on every ice cream sandwich you sell and suddenly thereʼs a price war, you may make only a nickel. Thatʼs not good. Itʼs called a barrier to entry or competitive insulation. Barriers can include patents (which donʼt work as well as most people think), brand names, exclusive distribution deals, trade secrets (like the recipe for Coke), and something called the first mover advantage.

Blockbuster Video, for example, created a huge barrier to entry when it opened thousands of video stores around the country. By the time the competition showed up, all the best spots were taken. As you can guess, this is a pretty expensive barrier to erect.

First mover advantage is the fond hope that the first person into a business, the one who turns it into something that works, has an advantage over the next one. For example, if you start mowing lawns in your exclusive subdivision, the second person doesnʼt get a chance to solve someoneʼs lawn problem—youʼve already done that. Instead, the second guy has to hope that he can undercharge or overdeliver enough to dislodge you from your spot.

3 THEY SHOULD BE SELF-PRIMING. One of the giant traps bootstrappers fall into is inventing business models that donʼt prime themselves. If you want to sell razor blades, for example, youʼve got to get a whole bunch of people to buy them. Without a lot of razors out there that can use your blade, you lose. Is it possible to build a paradigm-shifting business with just a little money? Sure. Itʼs been done before. But nine times out of ten, youʼll fail. Why? Because youʼre gonna run out of money before you change the world.

Don Katz started a business called Audible that allows you to download books on tape from the Internet. So you can find a novel youʼve always wanted to hear, type in your credit card number, and listen to it. The challenge Don faces, though, is that you need to buy a $150 Audible player to hear it. Without the player, it doesnʼt work.

So, in order to sell the books on tape (which is how he makes money), he first has to sell the player (on which he loses money). This is a business model for brave people!

Our friendly ice cream vendor has a self-priming business. Sure, he has to lay out some cash for that first truck and for the first batch of ice cream sandwiches, but after that it ought to pay for its own growth. Sell $100 worth of ice cream for $200, and you have enough money to buy yourself two cases of ice cream.

4 THEY SHOULD BE ADJUSTABLE. Remember how excited everyone got about the missiles the U.S. used during the Gulf War? Here was a weapon you could aim after you launched it. You could adjust the flight along the way. You need a business model like that if youʼre hoping to maximize your chances of success. If youʼve got to lock it, load it, and launch it, youʼre going to be doing more praying than you need to.

A business model that relies on a huge number of customers or partners is far less flexible than one you can adjust as you go. Subway sandwich shops, for example, have more than 13,000 locations, each individually operated. If Subway decided that the future lay in barbecued beef, it would take a lot of persuasion to get each of these entrepreneurs to go out and buy the necessary equipment. Theyʼre pretty much stuck with what theyʼve got.

Compare this to a local restaurant with one or two locations. If everyone suddenly wants fresh oat bran muffins, theyʼll appear on the menu in a day or two.

The ice cream business, which youʼre by now no doubt bored with, is totally adjustable. In the winter you can switch to hot chocolate. If business heats up, (sorry for the pun) buy more trucks…

5 THERE SHOULD BE AN EXIT STRATEGY (OPTIONAL). If you can build a business and then sell it, you get to extract the equity you built. If you canʼt sell it, all you get is the annual profit. There can be a big difference. About eight months after going public, Yahoo!, for example, had equity worth about a billion dollars, but it made only $2 in profit last year. That 500,000,000-to-1 ratio is huge, and itʼs unusual, and it doesnʼt last forever, but if your goal is a retirement villa in Cancun, the exit strategy it allows is very nice indeed.

Selling ice cream sandwiches offers no exit strategy at all until you reach a certain scale. When youʼre small, the business is just you. A competitor can buy trucks more cheaply than buying your business. But once you hire employees and build a brand and create trade secrets and systems, then youʼve built a business.

One of my favorite bootstrap businesses is the Stereo Advantage in Buffalo, New York. I was one of its first customers as a teenager in the 1970s, and since then Iʼve seen it grow from a tiny one-room shop to a business with hundreds of employees, more than 4,000 commercial accounts, a service business, a catalog business, and a huge share of the stereo, home the ater, cellular phone, and even casual clothing business in the markets in which it operates. Letʼs look closely at how the Advantage fares on the five rules of business models.

FIRST OF ALL, IT’S PROFITABLE. By relying on significant relationships with suppliers, it can buy cheap and sell sort of cheap. The profit on each sale isnʼt huge but the volume is, so thereʼs plenty of money left over at the end of the day.

IT’S PRETTY PROTECTIBLE. In the beginning, of course, the Stereo Advantage had nothing that couldnʼt be easily copied. But back then, no one wanted to copy it. Now, twenty years later, the store has built a significant brand, a huge array of loyal customers, a talented staff, ongoing service contracts, and deep, mutually beneficial relationships with suppliers. Many, many companies have tried to go after it, but all have failed.

IT’S SOMEWHAT SELF-PRIMING. The beginning was a very risk-filled time for the store. The owner had to buy inventory, take a lease, and hire staff without any guarantee that people like me would walk in and buy something on opening day. As it grew, though, each step has been self-priming. He brought in two televisions. When they sold, he brought in eight more. Now there are hundreds on display, without the risk that would have been incurred if he had filled the store with televisions before ever selling one.

IT’S ADJUSTABLE. If the core of the Advantageʼs business is that it combines a solid reputation with a good location and trustworthy suppliers, then the business can be adjusted a great deal within those parameters. When portable telephones got hot, for instance, it was easy for Stereo Advantageʼs owner to talk to Sony and other suppliers and get some in the stores quickly. Same thing with home theater.

Itʼs unlikely that the store could sell cars, or even profitably move into high-end stereos. But, within the constraints of its business model, it enjoys a great deal of flexibility.

Which leads to the exit strategy. Itʼs terrific. Any number of national retail chains could buy the Stereo Advantage and use it as a template for rolling out a national chain. The owner has managed to create a management team that doesnʼt require his personal involvement in every decision. In many ways, itʼs the ideal business to sell: too small to go public, but permanent enough to last beyond its founder.

Ray Kroc, one of the greatest bootstrappers ever, took a completely different tack. McDonaldʼs (which he didnʼt invent, by the way) was built with the intent to “scale” it—to make it bigger.

Ray found a restaurant in California, run by two brothers. They had a system. They knew how to make a great hamburger, super fries, and a wonderful milkshake. They had a look and feel that was easy to communicate. And a way to cook.

Ray decided that growing the business was the key to competitive insulation and profits. If he was the biggest, first, he would win. So he started franchising. He let others buy the right to build their own McDonaldʼs. The franchise deal was simple: a little money up front along with a share of the profits forever in exchange for the brand name, a rulebook, advertising, and unique products.

Letʼs take a look at the McDonaldʼs business model as Ray saw it in 1965 with regard to the five principles:

IT’S A VERY PROFITABLE BUSINESS. The cost of making the products is low, and a newly prosperous American public, fueled by a baby boom, is happy to pay for them.

IT’S VERY PROTECTIBLE. The brand name is powerful, and becomes more so every time any McDonaldʼs on earth runs an ad. And by being first in the market, it gets the best locations, which are worth almost as much as the brand. (Did you know that in 1997, on any given day, one out of seven Americans ate a meal at McDonaldʼs?)

IT’S COMPLETELY SELF-PRIMING. The brilliance of Ray Kroc was that he had other people fund his growth by paying up front for a franchise. The more he grew, the more funding he got. This is a much harder trick to pull off today, but itʼs not impossible.

IT’S NOT ADJUSTABLE. The giant risk Kroc took was that once people bought into his franchise, they didnʼt want it to change. So as long as it was working for everyone, everyone was happy. But what do you do with a location that just doesnʼt click? How do you introduce new products when competition comes along? And what happens when you open franchises in different countries? Perhaps the biggest hassle in the franchisorʼs life is maintaining flexibility when you have thousands of licensees around the world.

A recent episode is a perfect example of this lack of adjustability. Burger King, seemingly stranded in second place, reformulated its way of making french fries. With a huge national campaign, it attacked one of McDonaldʼs core products. But McDonaldʼs couldnʼt possibly respond with a new recipe quickly—the logistics are too cumbersome.

The exit strategy was terrific. Ray Kroc took the company public and became a very, very rich man.

Inventing a new business model is a very scary thing. The Internet is the home of scary business models, a place where new businesses open every day, many by people with no idea how theyʼre going to make a living.

Yahoo, Yoyodyne, HeadSpace, iVillage—each of these Internet marketing companies came at the marketing equation from a different angle. Each looks for a scalable, protectible model that will allow it to extract excess profits. But many Net businesses (and businesses in the real world) ignore this critical rule: Just because itʼs cheap to start doesnʼt make it a good business.

This is a big danger for the bootstrapper. You donʼt have anyone telling you you canʼt start a business. And if youʼre investing your time and just a little of your money, thereʼs not much to stop you from giving it a try. You donʼt need anyoneʼs approval!

JUST BECAUSE IT’S CHEAP TO START DOESN’T MAKE IT A GOOD BUSINESS

Soon after Staples started opening office supply superstores, an acquaintance of mine decided that heʼd start his own business. The idea was simple: He would go to larger companies and offer to sell them office supplies at a low price. Heʼd make the purchases at Staples and mark up the prices for his customers.

At the beginning, there was enough difference between what these organizations were used to paying for office supplies from their dealers and what Staples was charging that he could make a small profit on every sale. But my friendʼs idea fails most of the business model tests. The biggest problem is that once he took the time to teach these customers that price is the most important thing to look for when buying office supplies, theyʼd find out about Staples and switch.

This was a cheap business. He could start it for free. But it was a bad business, a business not worth the enormous investment of time and thought it takes to get started.

Donʼt fall into the trap of doing the easy business, or the fun business, or the sexy business. In the long run, any failed business, regardless of how cool it seems, is no fun.

The Inc. 500 is a list of the fastest-growing small companies in the country—and almost all of them are bootstrapped. Whatʼs interesting is how varied the businesses are, and how boring many of them are. Yet the people who are running them are having the time of their lives.

The #1 company on the list makes toothbrushes. Among other companies in the top 25, there is a company that markets clip art, another that performs custodial services for corporations, and a third that markets and distributes vegetables.

DO YOU WANT TO BE A FREELANCER OR AN ENTREPRENEUR?

As you consider different business models, you need to ask yourself the critical question above. This is a moment of truth, and being honest now will save you a lot of heartache later.

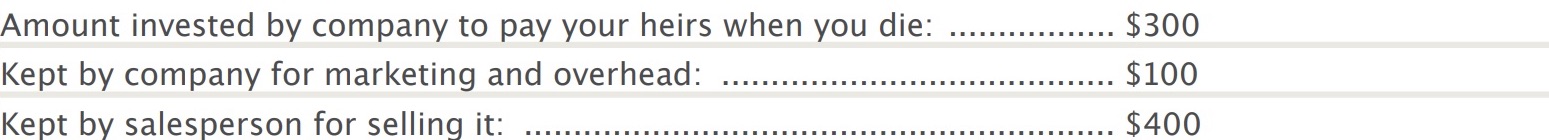

The difference? A freelancer sells her talents. While she may have a few employees, basically sheʼs doing a job without a boss, not running a business. Layout artists, writers, consultants, film editors, landscapers, architects, translators, and musicians are all freelancers. There is no exit strategy. There is no huge pot of gold. Just the pleasure and satisfaction of making your own hours and being your own boss.

An entrepreneur is trying to build something bigger than herself. She takes calculated risks and focuses on growth. An entrepreneur is willing to receive little pay, work long hours, and take on great risk in exchange for the freedom to make something big, something that has real market value.

If you buy a Subway franchise hoping to work just a little and get very rich, youʼre in for a big disappointment. The numbers of the business model donʼt support absentee management of most Subways. You, the franchisee, need to be the manager too.

Contrast this with the entrepreneur who invents a new kind of photo booth, then mortgages everything he owns and borrows the rest to build a company with 60 employees in less than a year. If it works, heʼs hit a home run and influenced the lives of a lot of people. If it fails, heʼs out of the game for an inning or two and then, like all good entrepreneurs, heʼll be back.

Both situations offer tremendous opportunity to the right person, and millions of people are delighted that they left their jobs to become a freelancer or an entrepreneur. But for you, only one of them will do. And you must figure out which one.

The entrepreneur is comfortable raising money, hiring and firing, renting more office space than she needs right now. The entrepreneur must dream big and persuade others to share her dream. The freelancer, on the other hand, can focus on craft. She can most easily build her business by doing great work, consistently.

This manifesto is focused on freelancers and early-stage entrepreneurs. Itʼs designed to show you how to thrive and survive before raising money. Because if you bootstrap successfully, youʼll find that bankers, angels, and investors are far more likely to give you the money you need to grow.

The most successful bootstrappers donʼt invent a business model. They trade on the success of a proven one. There are countless advantages to doing this. Here are a few:

1. YOU CAN BE CERTAIN THAT IT CAN BE DONE. If one or more people are making a living with this business model, odds are you can too.

2. YOU CAN LEARN FROM THEIR MISTAKES. If the guy down the street overexpands, you can learn from that.

3. YOU CAN FIND A MENTOR. Somewhere, thereʼs someone with this same model whoʼs probably willing to teach you what he knows.

4. YOU’RE NOT ALONE. The horrible uncertainty of staring down a bottomless pit doesnʼt afflict the bootstrapper who is brave enough to steal a business model.

Donʼt get me wrong! Iʼm not proposing you do nothing but copy some poor schmo, word for word, step by step. Instead, copy his business model. If thereʼs someone making a good living selling ice cream sandwiches from a truck, maybe you could sell papayas the same way. The business model is the same—same distribution, same competitive pressures, and so on. Thereʼs plenty of room for creativity when you bootstrap, but why not take advantage of the knowledge thatʼs there for you?

FOLLOW THE MONEY

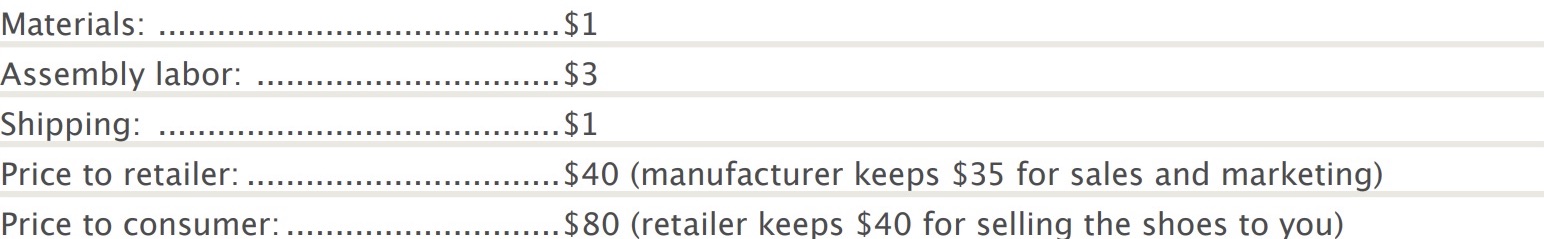

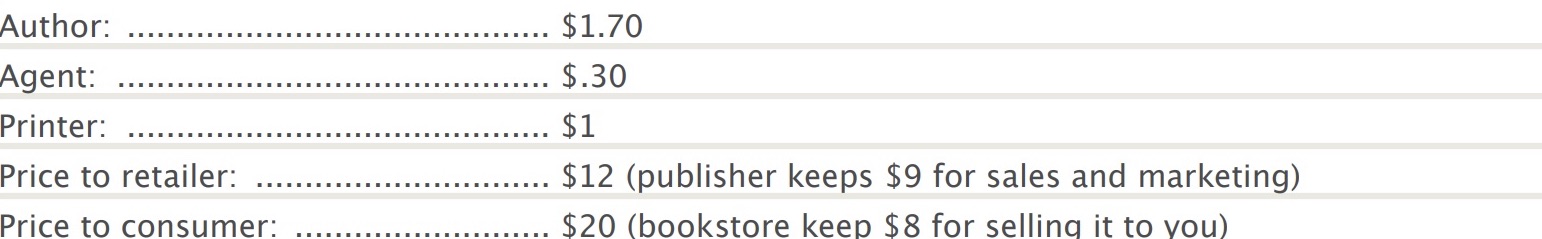

Understanding the value chain of your business is a great first step in getting to the core of how youʼre going to succeed. A value chain is the process that a product goes through before it reaches a consumer. Starbucks, for example, starts with a coffee bean in Colombia that is so cheap itʼs almost free. Then they roast it and transport it and brand it and make it convenient and brew it and sell it. At each step along the way, Starbucks is adding value—making the bean worth more to its ultimate consumer. The more value you add, the more money you make.

When looking at a business model and the value chain it creates, I like to start from the last step:

1. Whoʼs going to buy your product or service (called product for brevity from here on in)?

2. How much are they going to pay for it?

3. Where will they find it?

4. Whatʼs the cost of making one sale?

These four questions go to the critical issue of distribution and sales. The Pet Rock was probably the worst thing that ever happened to bootstrappers, because it led people to believe that they could turn a neat idea into nationwide distribution without too much trouble.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Getting nationwide retail distribution without money to spend on TV ads, a sales force or rep firm, and massive inventory investment is essentially impossible.

When you sell through existing retailers, they add a lot of the value that the consumer receives. They stock it. They make it convenient. They offer the reliability that their brand name connotes (itʼs guaranteed). And because they add so much value, they get to keep a lot of the profit. Look at it from their point of view. Macyʼs, for example, knows its going to sell 10,000 jackets this year. They can come from firm x or firm y. The Macyʼs purchasing agent is going to squeeze x and y as hard as she can to extract as much profit for Macyʼs as she can.

If youʼre selling a custom service or a high-priced good, consider selling it directly. That cuts out lots of middlemen, and leaves it in your hands. If you can make this self-priming, youʼve gone a long way toward making your company successful.

In most products, the single largest step in the value chain is the last one—those four items in that list. If you and your company handle that last step, youʼve earned the right to the profit that comes with it.

For example, an architect who brings in a contractor can expect to extract more profit (or savings for his customer) than the contractor who got the job and then brought in the architect.

Obviously, some service businesses lend themselves to direct sales more than consumer products do. What if youʼve got your heart set on bringing a fantastic board game to market? Are you doomed to be at the mercy of mass marketers and nationwide toy chains? Not at all. There are lots of places that sell board games that arenʼt Toys R Us. Catalogs, for example, can help you reach large numbers of consumers without taking personal risk.

So, to recap, letʼs restate each of the four questions that relate to the value chain:

1. WHO’S GOING TO BUY YOUR PRODUCT OR SERVICE? Define the audience.

2. HOW MUCH ARE THEY GOING TO PAY FOR IT? Do a value analysis to figure out what itʼs worth compared to alternatives.

3. WHERE WILL THEY FIND IT? Determine how much of the distribution of the product you control, and what value is added by the retailers or reps you use.

4. WHAT’S THE COST OF MAKING ONE SALE? Divide the cost of sales by the number of products youʼre going to make. Youʼve just figured out whether theyʼre worth selling.

The ice cream example is fascinatingly simple when it comes to these four questions.

1. WHO’S GOING TO BUY YOUR PRODUCT OR SERVICE? Hot kids on the beach!

2. HOW MUCH ARE THEY GOING TO PAY FOR IT? Buck each!

3. WHERE WILL THEY FIND IT? Truck comes to them—we find the best locations.

4. WHAT’S THE COST OF MAKING ONE SALE? Itʼs the cost of the driver and fuel divided by the number sold each hour.

This leads us to Question 5:

5. WHAT DOES IT COST TO MAKE, PACKAGE, SHIP, AND INVENTORY THE ITEM YOU JUST SOLD? If you know this, you can figure out:

6. WHAT’S YOUR PROFIT ON ONE SALE? And then you can guess:

7. HOW MANY SALES CAN YOU MAKE A MONTH? If we add in the cost of advertising, training, overhead, and the rest, youʼve just mastered the value chain. And youʼve discovered how you can make your business profitable.

For example, letʼs say it costs you $5,000 a month in overhead to run the machine that makes your products. The price of each product is $2 and the cost of each is just $1. If you can figure out how to boost your sales from 5,500 units a month to 6,000 units a month (an 11 percent increase), youʼve just doubled your profits.

Business model jocks call this “sensitivity analysis.” Itʼs a way of looking at the pressure points of your business. If you know these before you even open the doors, youʼll have a much better understanding of what to focus on.

Hereʼs another example. My father makes hospital cribs. Heʼs got a big factory filled with punch presses and painting bays and other awesome equipment. The plant is old, but itʼs paid for. A sensitivity analysis on his business shows that keeping the factory filled isnʼt the smartest thing to do. Thatʼs because labor and inventory and cost of capital are far more expensive to him than the carrying costs on his plant. The way he can maximize his profits is by making sure that every dollar he spends on personnel turns into the maximum amount of profit. In other words, he has to either raise prices or increase productivity to make more money.

Youʼre going to be running this business a long time. Spend an extra month to figure out what your business model feels like and save yourself some headaches later.

EVERYONE IS NOT LIKE YOU

Novelists are encouraged to “write what you know.” And the business you run should reflect what you know and love and are great at.

But donʼt fall into the trap of assuming that everyone needs what you need, wants what you want, buys what you buy. New Yorkers run around believing that everyone has a Starbucks on every corner, while entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley are certain that everyone uses a laptop all the time.

Itʼs so easy to extrapolate from our own experience and multiply it by 250,000,000. Donʼt.

When I interview people for jobs, I always ask, “How many gas stations do you think there are in the United States?” Not because I care how many gas stations there are, but because it gives me an insight into how people solve problems.

The vast majority of people who answer this question (Iʼve asked it more than 1,000 times over the years) start their answer with, “Letʼs see...there are 50 states.” They then go on to analyze their town, figure out how many gas stations there are, and multiply from there.

While this is better than some approaches, it is a ridiculous way to answer the question or to plan a business. North Dakota is not like Michigan! And your life, your neighborhood, your friends, and your needs are not like everyone elseʼs. The best way to answer the question is to start with a scalable metric—either cars (how many cars lead to how many stations) or, surprisingly, how many big gas companies there are. Either one will get you to a quick and defensible analysis.

Instead of starting the business that makes stuff for people just like you, do some real research. Go to the library. Donʼt invent something that requires you to have a handle on the purchasing habits, the psychographics, and the changing demographics of the whole country. Instead, find a thriving industry and emulate and improve on the market leader. Sheʼs already done your homework for you.

DON’T START A BUSINESS WHILE SHAVING! (A CAUTIONARY TALE IN SEVERAL ACTS)

Staring into the mirror this morning, using my brand-spanking-new Norelco razor, it occurred to me how easy it would be to start down the road to ruin while in the bathroom.

Imagine that our young hero is shaving and notices that the blades on his lift-and-cut razor arenʼt as sharp as they used to be. His best friend, he remembers, is a metallurgist, and maybe there would be a neat, inexpensive way to sharpen the blades in an electric razor.

A day of research in the drugstore and on the Web confirms what he already knows—there are a couple of razor-sharpening devices on the market, but they are hard to find, expensive, and not very good.

The entrepreneur arranges a business lunch with his friend. He extracts a promise to keep the big idea a secret, then describes his great insight: a low-cost razor-sharpening device that would work well.

Heʼs got a business plan. With projections, ad slogans, a corporate mission statement, a rollout schedule, the whole thing.

“Look,” he says, “there are more than five million electric razors out there. If we can sell to just ten percent of them, thatʼs five hundred thousand units! Figure a profit of four dollars a unit and weʼre rolling in dough.”

Following the instructions in the business books and magazines he reads, heʼs figured out an exit strategy and already has some angels in mind to finance the business. Right there, on a handshake, they agree to a partnership. The metallurgist will invent the device and own half the company. The entrepreneur will take it from there.

One month later, armed with plans, the entrepreneur heads for the best patent attorney he can find. He pays a $5,000 retainer and starts the process.

Then itʼs off to find a manufacturer. Intending to be conservative, he decides to build only 10,000 devices, noting, though, that the manufacturer needs to be able to ramp up on a momentʼs notice when this thing takes off like the Chicago fire.

I know what youʼre thinking. Wait, it gets worse.

Doing some math, our hero realizes that he needs $40,000 to pay the manufacturer. Also, heʼll need to hire some sales reps to carry his item. And he figures that a TV commercial (which will run just once, because heʼs on a budget) will help jump-start the distribution.

Suddenly, he needs $400,000. And heʼs doomed.

Actually, he was doomed that first day in the bathroom.

The cost of sale is enormous. Getting the first person to buy the first sharpener is unbelievably expensive. Itʼs a retail item, sold in a high-volume location (the drugstore). People donʼt know it exists and theyʼre not sure they want it. So you have to pay a bunch of money to let people know they need one, and then you have to share a lot of the profit with the retailer.

Consumer products are almost impossible to bootstrap. Especially consumer products that need to be sold in thousands of drugstores in order to be profitable. Take a look at your local CVS—the number of bootstrapped products there is small indeed.

It gets worse.

In order to sell a product like this, itʼs got to be in stock when the customer gets to the store. So youʼll need to make far more than you expect to sell in the next month or so, just to fill store shelves. But of course, retailers are not going to pay you in advance just to fill their shelves.

The biggest insult to the bootstrapper ethic is the fact that every customer needs only one for the rest of his life. Thatʼs right, after going to all the trouble of selling this item, our razor entrepreneur will never ever sell a replacement. The cost of sale is not leveraged across many sales. Hey, he wonʼt even get the benefit of word of mouth—would you tell a friend about an invention like this?

Unfortunately, the belief that the successful entrepreneur must have in himself is a doubleedged sword. Belief in a dumb business model can force you down a road that will eat away your time and your money. All the trappings of a successful business—business plan, marketing plan, finance plan, PR agency, patent lawyer, and articles of incorporation—can hide the real flaws behind a business.

And what about our hero? He gave away half the company to someone who didnʼt do much work and who was easily replaceable. Left with 98 percent of the work but just 50 percent of the company, heʼs never going to be able to raise enough money to launch this business. Lucky for him he doesnʼt have the cash in his retirement account—he might have been foolish enough to take the money out.

Successful bootstrappers know this: Your business is about the process. Itʼs not about the product. If you structure a business model that doesnʼt reward you as you proceed, it doesnʼt matter how much you love the product. Pretty soon there wonʼt be any product to love.

The bootstrapper is focused on finding a market that will sustain the process. A platform that responds to the work you do. With a business model that works, the deal is simple. You invest time, effort, and money. In return, your market responds with sales, cash flow, and profits.

But, you might be thinking, donʼt some entrepreneurs turn big ideas into big companies? What about Steve Jobs or Bill Gates or Phil Knight or Ted Turner?

What about them? They picked giant business models and got lucky. Someone had to. The market was ready, and they won. But their success is the exception that proves the rule. For every Bill Gates there is a David Seuss, a Phillipe Kahn, and 100 other super-talented, hardworking visionaries weʼve never heard of.

You can pick any business in the universe to bootstrap. I recommend picking one thatʼs friendly to bootstrappers, that wants you to succeed, that will likely give back what you put in. Itʼs easier to tell you what to avoid than to point you in the right direction. Businesses that are also hobbies usually cause bootstrappers the most trouble: restaurants, toy design and invention, creating gourmet foods.

On the other hand, mail order, consulting, acting as a sales rep or other sort of middleman, all work great. So does focusing like a laser on a very obscure market that is growing fast.

Maybe it wonʼt make you as famous as Spike Lee or Marc Andreesen. Thatʼs okay. It will make you happy.

HOW TO BOOTSTRAP A BUSINESS THE SMART WAY

I have a friend who can do miraculous things with fabric. Iʼve seen her turn leftover clumps of velvet into a show-stopping shawl. And she adores kids.

She decided to break into the toy business. For four years she tried to sell a better diaper bag to Fisher-Price or a new kind of catch toy to Mattel. She went to the right trade shows, got the right meetings, was careful about whom she associated with, how she positioned herself, and how she pitched her goods. She watched her expenses like a hawk. And she kept 100 percent of the equity.

There were some close calls. Fisher-Price starting going to contract on the diaper bag. Mattel asked for more details. But each time, at the last minute, the company turned her down.

My friend eventually realized that she was competing in a world where she wasnʼt wanted. Toy companies work hard to keep inventors away, because theyʼre scared of lawsuits and the hassles of dealing with outsiders. Theyʼre not overflowing with happy, Tom Hanks–like luminaries, looking for the next Big Idea. The toy industry is a business, and a cutthroat one.

She had made a mistake. She built a business without a business model. She tried to invent a process that could turn into a living, to become a freelancer with a royalty stream in an industry where there were very, very few role models. She could still design her clothes and bags as a hobby, but she knew it wouldnʼt give her enough income to make a living. She had to find another way.

She took a look around and realized that the book business publishes 50,000 new ideas every year, relies 100 percent on outsiders, and hires editors who look for ideas from the outside.

Armed with this knowledge, she spent some time getting to know her customer base. Here were thirty major publishers, all with money, all eager to buy something, all willing to pay money in advance.

Here was a totally different industry in which the process she had worked on for four years would work. The system of meeting people, inventing products, licensing them, and earning a profit—the system she had tried to build in the toy business—was working every day in the book business. Different products, same job.

After six months of hard work, she was able to get meetings with three publishers who shared her vision of the market. She listened hard. She worked to understand what they wanted, what their customers wanted, how the industry worked.

Without spending any money, Lynn was able to understand the market. She was able to invent some concepts for books that she thought might sell. And then she was ready to get serious. So she found illustrators and researchers who could capture the messages she was trying to communicate. And she didnʼt give them equity—instead, she paid them a share of the front money.

One publisher decided that her concept for a calendar was worth a shot. They paid her a small advance and published it. Two years later, My friendʼs company has more than 2,000,000 copies of their work in print. Her calendars are often at the cash register at Barnes & Noble. Sheʼs been hired as a spokesperson by a nationally marketed brand, she makes products she loves, she gets fan letters from people all over the country, and sheʼs having fun.

Did she succeed because the her calendar idea was the most unique, original idea in the history of publishing? Or because she was a skilled novelist? Not at all. She succeeded because she understood what her market wanted and because she persevered for years and years to build her reputation. She was careful with expenses, didnʼt waste her equity, and set herself up for success while protecting against failure.

All without a bank loan. All without a patent lawyer. All because she picked the right business model, selling a product in a way that made sense to people who wanted to buy it.

THE SHEER JOY OF GETTING IT RIGHT

As Lynn's story illustrates, when youʼre in the right place at the right time with the right product, you can make it work. A lot of what Iʼm talking about in this manifesto might dissuade you from taking the bootstrapper journey. So many opportunities to fail, so few to succeed, it seems. But when it clicks, the magic that takes over is intoxicating. Your work, embraced by a stranger. Itʼs a rush.

Back in 1986, when I was first starting out, I sent a direct mail letter (by Federal Express) to forty different companies. Each firm was offered the chance to buy advertising in a book I was doing—for $1,000 a page, two pages minimum. I had figured in a huge profit margin, so all I needed were a few positive responses to make it worth the effort.

Within 48 hours, the phone started ringing. Within thirty days, I had sold more than $60,000 in advertising. Itʼs the thrill that comes from this kind of success that keeps you going. Iʼm not sure that the idea behind the advertising book was the most insightful or profitable Iʼd ever had. But by persevering, by putting concepts in front of people in a solid, benefits-oriented way, I had succeeded.

Another time, I had the idea to create SAT prep books. The proposal went to about a dozen publishers. Most of them were a bit interested, some called for face-to-face meetings, and one or two seemed on the verge of making an offer.

We proposed to the publishers that we would auction off the right to publish these books, a common practice in the publishing world. The publisher who paid the most money at the auction would get the right to be our partner in bringing the books to market. Then an editor from Doubleday called. “Cancel the auction,” she said. “What will it take to buy it right now?”

She made us an offer of about $150,000. I said it wasnʼt nearly enough. I was bluffing. She doubled her offer. “Nope,” I said, sweating now. After two long days of her bidding and my saying no, we ended up at just over $600,000.

Youʼll have days like this. Youʼll fail and be rejected and struggle, and then youʼll have days like this. Because youʼre a determined, focused, cheap bootstrapper intent on creating firstrate products. When they come, savor them!

ONE GOOD REASON NOT TO PLAN SO MUCH

Remember when I said I like to ask people how many gas stations they think there are in the United States? Well, the worst answer (and the main reason I ask) is, “I donʼt know.”

My response is, “I know you donʼt know. I want you to make a smart guess.”

Nine times out of ten, people refuse, in one way or another, to guess. They donʼt want to be wrong.

Most people hate to be wrong. They hate to make a statement (or, even worse, to write something down) and then be proved wrong. They donʼt like to buy the wrong car, vote for the wrong candidate, wear the wrong shoes.

Starting a business is the most public, most expensive, riskiest way of all to be wrong.

Faced with all the sensitivity analysis and business model mumbo-jumbo I talk about in this section, you might find it easy just to give up. “Iʼm never gonna be as smart as Bill Gates, so I give up!” Yeah, well, Bill Gates isnʼt so smart. Bill Gates thought the Internet was a fad. Bill Gates launched three database systems, all of which failed.

Thereʼs never been an entrepreneur with a crystal ball. Thereʼs no way to know for sure whether your business is going to work, whether your targeted customers will buy, whether your choice of technology is a good one. Youʼre going to be wrong. Get used to it!

In the face of this uncertainty, it seems to me that the very worst thing you can do is fail to try. I went to business school at Stanford, which prides itself on being very entrepreneurial. Of the 300 people in my class, at least half publicly proclaimed that they were going to start their own businesses sooner or later.

Now, twenty years later, only about 30 of us have actually done it. The rest are still waiting for the right time or the right idea or the right backing. Theyʼre waiting for an engraved invitation and some guarantee of success.