It's Your Turn: Make Something That Matters

Two people are on an escalator.

We know they are executives because, in addition to being well dressed, they appear stressed and in a hurry. Suddenly, with a lurch, the escalator comes to a stop. Both executives are now trapped on a broken escalator, apparently unable to get to safety. The first executive sighs in frustration, while the second starts calling for help. Here are important people, executives, unable to get to where they need to go because the escalator has broken and there is no one to fix it or rescue them.

In 2006, Tim Piper turned this modern parable into a commercial for a company called Becel. The virality of the video is a testament to the absurd truth of Piper’s vision. Too many of us are unable to see that all we have to do is walk right off the escalator. The stairs are there, they’re part of it. They’re not as automatic or as convenient as a functioning escalator, but they beat being stuck.

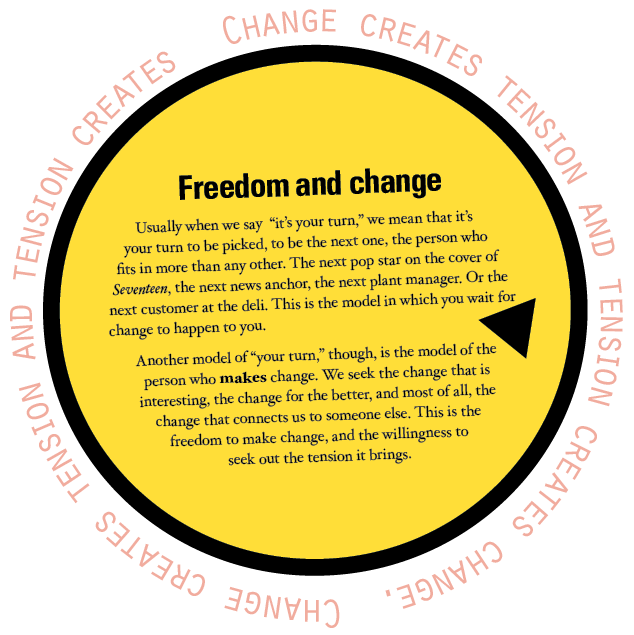

It’s about realizing that it’s your turn, always your turn, and understanding that once you see the opportunity, it’s yours. Most of all, it’s about freedom and our almost automatic insistence on avoiding it at all costs.

The opportunity is freedom

The freedom to connect, to reach out to just about anyone in the world.

The freedom to create, to sing and write and invent and share widely.

The freedom to lead, to stand up and say, “follow me.”

The freedom to learn, to take almost any course on any topic and to put that learning to work.

The freedom to choose your next project, the information you consume, and the people you associate with.

We live in a world that’s still filled with barriers and limits, a culture where too often people are judged, stripped of their dignity, and denied true freedoms. But at the same time, the economic and technological shifts around us have created an entirely new class of ruckus makers and have given people the freedom to stand up and acknowledge that it’s their turn.

Now, more than ever, more of us have the freedom to care, the freedom to connect, the freedom to choose, the freedom to initiate, the freedom to do what matters.

If we choose.

The problem is freedom

Not that we don’t have enough freedom but that we can’t handle the freedom we have. Or more accurately, we believe we can’t handle it.

Freedom brings the appearance of risk, freedom brings responsibility, freedom means we must make a choice.

"Man’s brain lives in the 20th century; the heart of most men lives still in the Stone Age. The majority of men have not yet acquired the maturity to be independent, to be rational, to be objective. They need myths and idols to endure the fact that man is all by himself, that there is no authority which gives meaning to life except man himself. … modern man still is anxious and tempted to surrender his freedom to dictators of all kinds, or to lose it by transforming himself into a small cog in the machine, well fed, and well clothed, yet not a free man but an automaton." —Erich Fromm

The fear of stupidity

Stupid is not uncommon. Stupid is the way we feel when working on a difficult problem. Stupid is the emotion associated with learning—we are stupid and then we are not. The pre-learning state is stupidity.

A scientist might work ten years on solving a problem of math or logic or biology. Or a lifetime. And until the problem is solved, she’s stupid. And then she isn’t.

Which is all fine, actually.

The problem comes with the emotion that we’re supposed to feel when we feel stupid: Fear.

We are supposed to be afraid of stupid, to get stupid over with as soon as we can.

Change, of course, makes everyone feel stupid, because change breaks all the old rules, inventing new ones, rules we don’t know (yet).

And so the equation is obvious: Change —> Stupid —> Afraid.

One way to avoid this is to avoid change.

One way to avoid this is to avoid freedom.

The best way to avoid this is to embrace stupid and skip the last part.

There’s nothing to be afraid of. Nothing except avoiding the feeling of stupid.

And stupid is a good thing.

Making everything okay

There are three problems with freedom:

Things often don’t turn out precisely the way we hope.

Resolution takes too long.

And we might fail.

And so, when it’s our turn, we take a pass. It’s far more reliable to stay where we are than it is to leap, to jump to a new place different from the one we’re in.

But there’s an alternative. The alternative is to assume yes [and] no. To bet on failure [and] not failure. To realize that there’s a third state, the state of not knowing, of not landing, of not yet.

Not everything has to be okay.

Perhaps it might be better for everything to be moving.

Moving forward, with generosity. Moving forward, with a willingness to live with the tension. Moving forward, learning as you go.

The person who fails the most, wins.

The cost of a broken promise

You’ve almost certainly heard of the marshmallow test, research done by Walter Mischel over more than forty years at Stanford University. The short version: Small kids (three to five years old) are put in a library and offered a deal:Here’s a marshmallow. If you eat it now, we’re done, but if you wait fifteen minutes and the marshmallow is still here when we come back to you, you get two marshmallows.

It turns out that this single indicator of self-control and the ability to resist resolution is incredibly accurate. Twenty years later, the kids who showed they could wait ended up being happier, wealthier, on a better path forward.

New research makes something very clear, though: Kids who didn’t think the promise of two-for-one would be kept ate the marshmallow right away. Of course they would, wouldn’t you? The home you grow up in and the culture you live in matters more than we can imagine.If you are raised in a chaotic environment filled with broken promises, it’s incredibly difficult to bet on the future.

Industrialists made all of us promises as we grew up. Promises about the rewards of doing well in school or being obedient. Promises about good jobs waiting for us, about upward mobility, about fairness. As the industrial era fades, those promises are being broken for too many.

The opportunity that the connection economy brings with it offers a different set of promises, promises about freedom and taking your turn and doing work that matters. And it’s not at all surprising that so many are hesitant to take action... we eat the marshmallow instead because, hey, we’re used to our system breaking its promises.

Of course we’re wary of a glistening new offer, especially when it involves so much fear and requires us to trust others (and ourselves).

Pythagoras and the fifth hammer

Pythagoras, the guy who invented the hypotenuse, led a cult of brilliant but sometimes confused mathematicians. They believed that harmonics held the key to understanding how things functioned. At the heart of their work was the study of ratios, of dividing things into their basic components in search of the harmony of the universe.

According to the myth, Pythagoras was stuck on a theory, and he went for a walk to clear his head. He passed a blacksmith’s shop and heard five workers inside, all using hammers to bend iron. As their hammers struck in unison, the clang organized into a beautiful sound, with all the hammers singing out in harmony at once.

He walked into the blacksmith’s shop and, with a bluster that would have been fun to watch, took all five hammers away with him. He wanted to study what made their harmony so beautiful... it might unlock the secret he was seeking.

Over the following weeks, Pythagoras weighed and measured each hammer. He wanted to understand why they didn’t sound identical and, more important, why they sounded so good when they all clanged in unison.

His work helped us discover a physical connection between math and the world.

It turns out that the ratios in the weights of the first four hammers led to their ringing inharmony—each had a weight that was a multiple of the other. More fascinating to me, though, was that the fifth hammer didn’t follow any of the rules. The fifth hammer was spurious, data that didn’t fit, something to be ignored.

Like many researchers throughout time, he threw out the fifth hammer (and the pesky mismatch) and published his work only about the first four. But it turns out that the misfit, the fifth hammer was the secret to the entire sound. It worked precisely because it wasn’t perfect, precisely because it added grit and resonance to a system that would have been flaccid without it.

The harmonies of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young worked best because of Neil Young. Because his voice wasn’t quite right. Because he’s a loose cannon. His sound is not quite right, so it works.

During their breakthrough tour in 1974, the core trio traveled together, often by private jet, from gig to gig. Young refused to fly with them, instead leaving immediately after each concert and driving with his son to the next gig in an old mobile home.

He was their friction, the wild card, the fifth hammer. The fifth hammer is the one that’s not proven, obvious or beyond discussion.

The fifth hammer is you, when you take your turn.

What happened at Solvay?

In 1927, the Solvay Congress in Brussels assembled 29 physicists. This photo captures the all-star line-up, titans including Heisenberg, Einstein, Curie and Bohr. Seventeen people in this photo won the Nobel Prize in Physics.

The extraordinary thing: Many of these people won the Nobel Prize after the conference was held.

They didn’t get invited because they had won the Nobel Prize. They won the Nobel Prize because they got invited. People like us do things like this.

Yertle.

In New York, it’s the top of the real estate market that keeps booming. Specifically, penthouses, the very top floor, with the high ceilings and great views.

I watched as a building was going up the other day, and wasn’t surprised to see that the top floor was significantly taller than the floors below. Penthouses have bigger windows, too.

Here’s the thing: When you’re in the penthouse, enjoying the windows and the view and the high ceilings, you have no idea whether there’s an apartment above yours. In fact, it probably shouldn’t matter, should it?

But it does.

Like Yertle the Turtle, who not only needed to be high up but also needed to be on top of everyone, the penthouse dweller is paying for supremacy, for being the unqualified winner on top.

The need to be recognized as the winner destroys your ability to take your turn, because taking your turn requires you to be willing to not win.

My argument is the only long-term way to make it as an artist is to do it from a position of generosity, of seeking to connect and change people for the better. But generosity, while it sometimes leads to it-feels-like-winning can never be based on winning, because winning requires other people to lose.

Yertle-style.

Program or be programmed

I know the words to the theme of The Dick Van Dyke Show. I also know that the music was written by the same guy who wrote the theme to Perry Mason. I have seen every episode of The Prisoner and just about all of Seinfeld

as well. Which is why I’m particularly qualified to talk about not watching television or, more specifically, making the choice to be a programmer, instead of being the programmed.

Television demands passivity. It entrains us with the masses, all mesmerized by a glowing electronic hearth, all in sync, all in the service of what the media company wants to sell us.

Teams of people are working hard to get you hooked and keep you hooked, so they can profit. Twenty or more hours not spent reading, not teaching, not connecting, not experimenting, not failing, not growing, and generally not making a ruckus. For many people, it’s more than fifty hours a week of not making a difference.

It’s a trap that allows us to exchange our time for a place to hide out from the challenge of learning to program.

Program a computer. Program a conference. Program a blog or a book or a movie you contribute to. Make it, don’t watch it.

Either you’re the creator or you’re the audience. Either you’re waiting your turn or you’re taking it.

On the hook.

Some people hate this.

If it’s actually up to you, if your turn is just waiting to be taken, if the microphone is right here—then who’s responsible when you back away?

If acquired traits like resilience and persistence and generosity are more important than genes and talent, then who can we possibly point to when things don’t go well?

It’s the other people, it’s the bureaucracy, it’s the unfair system. Blaming anyone but us is soothing and comforting.

The alternative is to be on the hook, to see the opportunity that comes with freedom, the choice to make a difference and to matter.

Being on the hook is a privilege. It means the people around us are trusting us to contribute, counting on us to deliver.

It’s not something to be avoided.

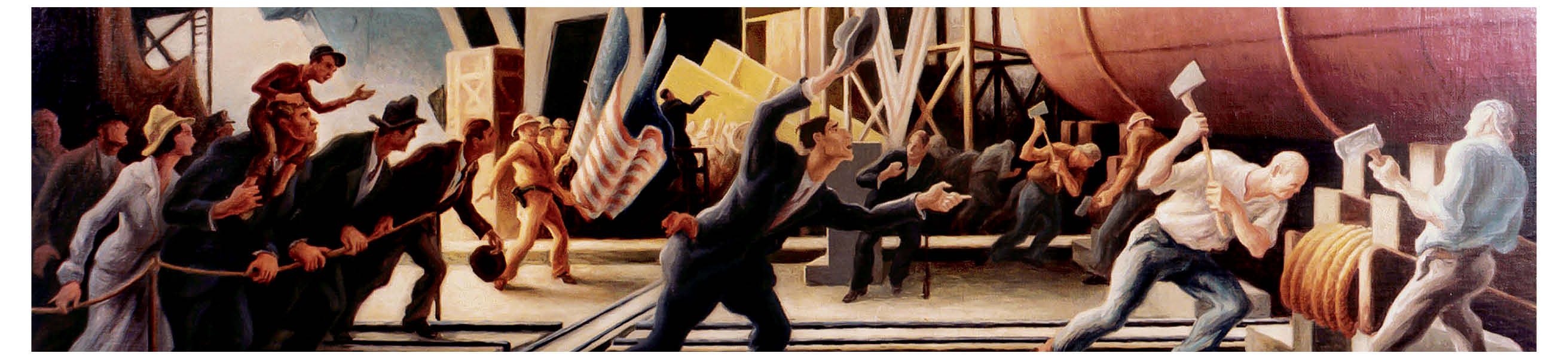

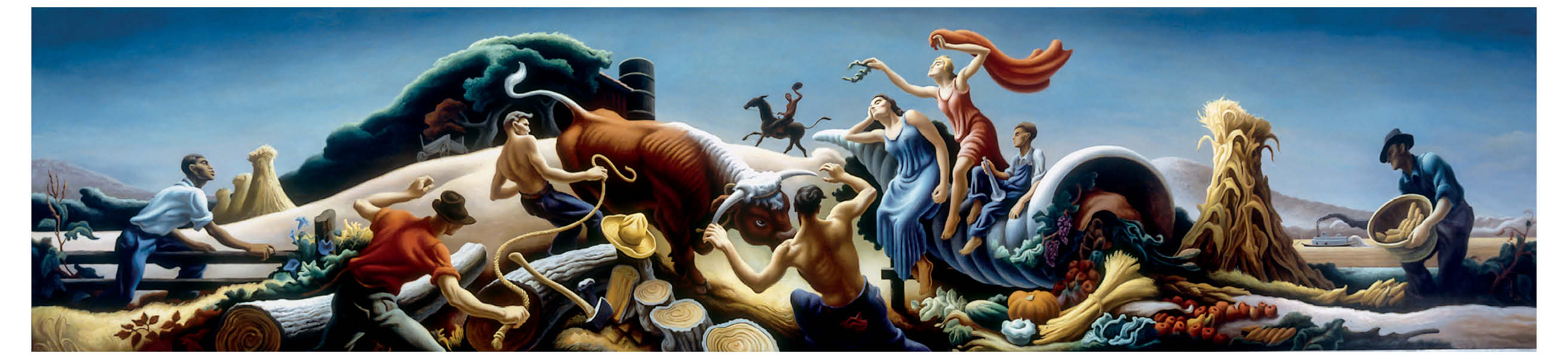

Charles Pollock was a painter

His brother Jackson, was an artist.

The reason that you’ve never heard of Charles is simple: He painted just like his teacher, Thomas Hart Benton did.

Benton’s murals and heroic imagery represented an important turning point in American figurative art. And Jackson Pollock blew most of it up when he created action painting.

Brother Charles, though, didn’t cause change, didn’t take his turn, didn’t choose to be on a vanguard.

Instead, he painted the way he had been taught to paint.

By a master, certainly, but still a copy.

To be an artist

Is to be on the hook

To take your turn

To do things that might not work

To seek connection

To embrace generosity first

To take responsibility

To change someone

To be human