One Room, One Team, Different Purposes

It was early days in my time as an internal team effectiveness consultant at Mars, Inc.

It was early days in my time as an internal team effectiveness consultant at Mars, Inc.

We were in one of the more peculiar hotel conference rooms I had ever worked in: long and narrow with a low drop-panel ceiling and smoked-glass mirrors along its two long walls. On the floor was a threadbare, reddish carpet, with a royal crest sort of pattern, that smelled of cleaning chemicals and stale cigarette smoke. It looked and felt like a cheap, cramped New Jersey interpretation of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. I was there working with a cross-functional brand team on their team effectiveness and we had reached an impasse.

Things had gone uncomfortably quiet in our mirrored cave. Finally, I broke the silence with a flurry of questions that arose out of my frustration, my sense of impending failure, but also from a genuine need to know: “What is it exactly that you’re supposed to be doing as a team? I mean, why do you come together? For what purpose?” I wondered how they were supposed to achieve any kind of high performance when they didn’t even know why they existed as a collaborative unit, as a team. The silence that followed my questions was telling.

Weeks earlier I had been asked by the team leader to sit in on a few of his regular team meetings in preparation for the workshop at the Hall of Smoke-and-Mirrors just described.

The typical meeting consisted of about a dozen associates in a non-descript conference room with overhead lights switched off; horizontal blinds lowered and closed. The only light came from the spreadsheet projected onto a large screen at one end of the room. A few associates would be working their Blackberries just below the level of the tabletop, like secretive virtuosos of the digital thumb piano. Alongside the low hum of the projector, three of the team members would be in a heated argument about the rows and columns of tiny, barely visible numbers on the big screen. Every so often, a head would pop up from one of the computer screens or Blackberries and this person would jump into the spreadsheet debate. Then just as quickly, once her point was made, she would return to the email or PowerPoint that was otherwise consuming her attention. It was impressive in a way, that ability to jump in and out of the conversation. But it was clear that none of them were giving their full attention and therefore the full value of their presence to any of what they were doing.

A question occurred to me: What if each of these people had a number scrawled across their foreheads, a dollar amount that represented their salary, wages and benefits on an hourly basis? What if our general manager suddenly walked into this room, and quickly calculated the cost to the company of this day-long meeting? I wondered if he would conclude, as I had, that most of these people would be vastly more productive and generate greater value for the business if they were at their desks, or in the factory doing what they were primarily hired to do, instead of sitting in this dimly glowing chamber trying to empty their crammed inboxes or get presentations written while being repeatedly distracted by a debate that didn’t involve them?

I have been in some pretty awful meetings in my career, and this one was no worse than others. It occurred to me that the meetings themselves weren’t the problem. New products had to be conceived of, planned for, costed out, tested, and launched into the market. Cross-functional collaboration—or at least cross-functional involvement—was and is essential to this complex, multidisciplinary process. As a collaborative effort the meeting was lousy, but work was getting done, albeit much of it unrelated to the topic of the meeting.

The people weren’t really the problem, either. Every one of them was a solid associate. They were there because good team players show up at meetings. Moment by moment as the meeting unfolded, each of them was doing what they thought was most important and valuable to do, whether that was working through their emails, building presentations or debating the projected spreadsheet.

The attitudes towards this meeting, and behaviors in it, and in so many others I have observed, were symptoms of overworked individuals thrown together in a badly conceived meeting. Something else, though, was going on. It struck me that this team didn’t know, or had forgotten, why they were all in there, together. Beyond their assumptions about the goodness of teamwork, the need for collaboration in a process such as the one at the heart of their meetings was unclear. Each one of them was probably very clear about how they, as individuals, were supposed to contribute. But they didn’t, as individuals or as a collective, behave as if they understood how their being together was intended to add value over and above their individual contributions. In fact, their enforced togetherness was getting in the way of individual work, work that was probably just as important as anything they might pay partial attention to in their meetings.

They knew their individual jobs and their individual value but were completely unclear about the job and the value of the team as a team.

Flash forward a few weeks to our faux-Versailles, where I eventually asked the leader and his team questions that had begun to take shape weeks earlier:

- What is it exactly that you are supposed to be doing as a team?

- Why, for what purpose, do you come together?

The answer I got didn’t surprise me: “We haven’t really thought about it. We’re all supporting this brand and we all just assume that we need to be here for these meetings. Besides, you never know, something may come up that needs input from one of us so we figure we need to be present. Just in case.”

OK, a reasonable rationale. But not compelling enough for this group to be able to create any real value through their collaboration. What’s more, I knew that it wasn’t just this team that was struggling. Other teams in other functions and in other companies where I had worked and consulted over the years were having similar experiences. Taken in total, what were teams who were operating in this way costing organizations in terms of wasted time and the negative impact on employee morale and engagement? How much money was being ill-spent between these frustratingly unproductive meetings on relatively ineffective team- and trust-building exercises that were meant to somehow correct for all this wasted time and effort? What would it be worth to us to turn this situation around, and what would it take?

These were questions I couldn’t answer, at least not without digging deeper. Quantifying the costs of the wasted time and effort was beyond my skills. But common sense suggested that the opportunity was big. Once I did the research, the answer to the “What-would-it-taketo-turn-it-around” question was both stunningly obvious and, so far as I could tell, almost completely overlooked.

Just as I was arriving at these unsettling notions about how teams were working, or trying to work, my one-man internal consulting practice embedded at Mars, Inc. was taking off. I was quickly becoming involved with teams at all levels and in countries around the world involved in all of Mars’ business lines including pet food, candy, and veterinary services. They were exciting times, but I couldn’t help but think I was plying my trade with an inadequate toolkit and flawed assumptions about what makes collaboration really work. Only later would I discover that I was experiencing first-hand the cost of the tension between individual effort and teamwork.

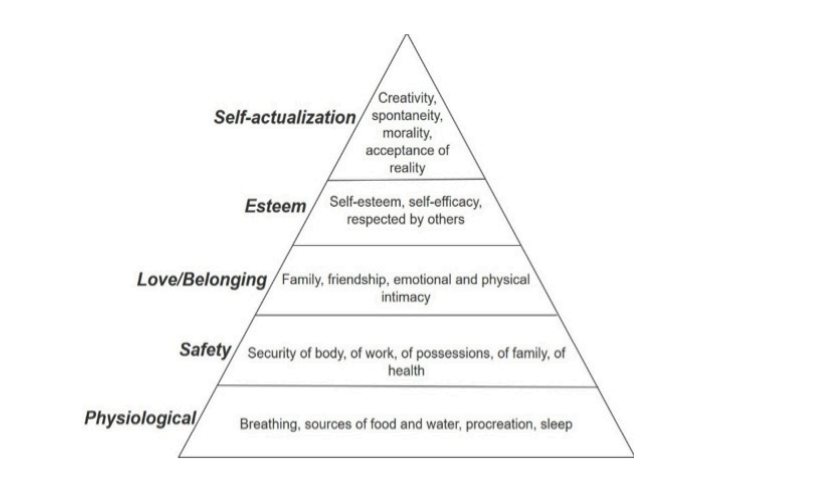

This tension crystallized after over 20 years of experience and research, learning about what real collaboration is and what drives that collaboration. So why is collaboration so hard to get right? While humans are great cooperators, it might surprise you that we aren’t coded to collaborate. All you need to do is refer to that handy pyramid otherwise known as Maslow’s Needs Hierarchy.

Our most fundamental needs, those towards the bottom of the hierarchy, deal with physiology and safety and are self-oriented: things like breathing, eating, mating and staying alive. Even though food and sex are usually better when someone else is with us, it’s generally true that when things get tough or scary the first thing I’m going to think is, “How am I going to deal with this problem and save my butt and the butts of my progeny?”, not “How am I going to work with you to deal with this?” Which isn’t to suggest that we’re never there for each other.

What about altruism? There’s a lot to be said for altruism and the potentially powerful drive to sacrifice oneself for the benefit of others. We hear with regularity about people putting themselves at risk to save others, in war in particular. From my interviews with veterans and members of the military about their combat training, being there for your comrades, having one another’s backs, is literally drilled into recruits for months. This kind of intensive conditioning, though, isn’t seen in large, non-military institutions like for-profit corporations.

Then, there is this question: Are altruism and collaboration the same? Is helping others coming from the same mental/ emotional place as working with others? I don’t think so. Altruism by definition expects no tangible reward or quid pro quo. Collaboration, on the other hand, is all about shared outcomes and mutual expectations. What is more, in studies of charitable giving, altruism has been shown to be driven in large part by what it provides to the giver, the self. “Warm-glow giving,” as it has been called, describes that feeling that the giver gets from his or her act of generosity. Other self-oriented feelings like guilt, social pressure and even social status have also been found to drive altruistic behavior. In other words, altruism isn’t about us, It’s about me.

In the modern, Western world, most of our enterprises are designed to take advantage of our more common, or at least more easily accessed, self-first orientation. For example, the most common organizational structures, also called hierarchies, play strongly to the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid, to our instincts to take care of and work for ourselves first.

In a traditional large organization, you will find hundreds, thousands, or hundreds of thousands of generally decent, me-centered people laboring away in an environment optimized to take advantage of this perfectly natural human tendency. Things like performance management, pay, recognition and rewards are all typically geared to individuals and they play on this individual survival mechanism. Therein lies the biggest problem with teams and collaboration at work. We preach collaboration, and talk about teamwork, but all the while organizations are optimized to manage, foster, and reward individual effort.

Collaboration is important, and there are ways to improve it even in large multinational corporations, but one way is to know when not to require it—when attempting to get more people together actually undermines people’s ability to accomplish their everyday goals and collaborate in more meaningful ways.

Here’s a simple rule of thumb: Have a team meeting only if every member of your group or team has something at stake when attending. If your meeting doesn’t feel to every person invited like it’s creating value for them, like it’s worth their limited time, skip it. Find another avenue for getting done what you need done. Most of the collaborating in a team is done by sub-groups of two or three people. Much of the rest of the work is handled by individuals. These two types of work most often do not require team meetings. Subgroups meet whenever they need to, to advance the work they share. I don’t think of these as meetings, though. I consider them working sessions. Even working sessions aren’t always necessary; For small groups, a lot of collaboration can happen without them. They can (and sometimes must) do this by working asynchronously.

Meet only when and if your meeting aligns with the team’s shared purpose. This ensures that what happen at your meetings will feel important to every attendee. If the work doesn’t meet these criteria, find other ways to get it done.

This is how you’ll ensure that when you do get together, team members will feel the meeting has worth and you’ll get the best from everyone. You will have provided them with an experience that feeds and satisfies their individual need to achieve and, therefore, achieves what you intend for the entire group.