The Teamwork Imperative

Teamwork is a (if not the) quintessential and critical element of organizational life.

Over 90 percent of what we do in our work lives happens through collaborative effort. That makes teams and teamwork the most important means of output and productivity in the organization. I think most organizations and people would agree with this statement.

Yet, most organizations treat teamwork as if it happens by magic. They label a group of people at work “a team,” and assume they will derive all the associated benefits. They assume everyone knows how to work in a team, that the only time a team needs development or formal intervention is when it is overtly in trouble. They see no need for organizational strategy for teaming, acting as if all teams are basically the same and can be managed and led in the same way. They see no real difference between the traditional team, the project team, the virtual team, or the teaming work group. If an ideal is required for motivation, they pick a favored sports team and hold them up as the shining example and do what they do. They squash conflict because good teams don’t “do” conflict. They believe that teams should have fun! Your organization’s leaders have told you they believe in teams, that they are even a core cultural value, so get on with it, they trust you—just not with budget, and please make sure that you do not make any decisions without getting approval. But, you are empowered as a team. Oh, and most importantly, senior managers and executives will as it suits them, countermand your leaders’ decisions and you should not be surprised or upset, because they know how to do your job better than you do.

Recognise any of the above?

When one considers the vast majority of organizations, the sentiments above seem to predominate. You would think that organizations would treat team performance as a strategic imperative, but most do not, preferring to muddle on with poorly performing teams and accepting mediocrity. There needs to be a big attitude change, and it needs to happen now.

Only 10% of teams are high performing, a frightening 40% are dysfunctional and detrimental to members experiences and lives, leaving 50% which are performing at best with small incremental results. This is what most organizations accept. I consider it unacceptable, particularly when delivering high performing teams is not rocket science. It does however, take effort, it does take strategy, it does take time, it does take budget, and critically it takes persistence and commitment from the organization, leaders, and team members.

So, what do you have to do to create a real teaming environment where high performing teams are the rule and not the exception?

To begin with, you have to get some facts straight and drop much of the nonsense that surrounds the concept of teams in the workplace.

1. Team Development and Teamwork are Fun

No, they are not. Work is work and fun is fun. Fun is defined in the Oxford English dictionary as “behaviour or an activity that is intended purely for amusement and should not be interpreted as having any serious or malicious purpose.” Now tell me what that has to do with the world of work? The fact that it can be an enjoyable experience to work in an effective team should not be confused with it being fun. If the team wants fun, absolutely go out for an evening of bowling, five-a-side football, or a good meal. These are good things to do, and they can be fun, but do not confuse them with the hard work required to develop and maintain an effective team. Real team development does not happen up the side of a mountain, putting life and limb at risk once a year or completing exercises with no connection to the reality of the workplace. Real team development that delivers sustainable development and effectiveness happens in the work place day-to-day. Give time to tackling real issues for the team—not worrying about how to build a house of straws, build a raft, or build trust by falling backwords into someone’s arms. I come to work to work and I would much prefer to give of my time with my colleagues dealing with and finding solutions to real work challenges. Team members are much more likely to be engaged, committed, and enthusiastic if they are dealing in reality where their opinions and ideas and inputs to real challenges of the team are welcome and actually considered. In other words, doing the work they are employed to do. Enjoying your work is important, having fulfilling work is motivational, being challenged is good (most of the time), but do not confuse this with fun. Work is serious. Please knock this fun nonsense on the head and do what needs to be done.

2. Using Sports Analogies

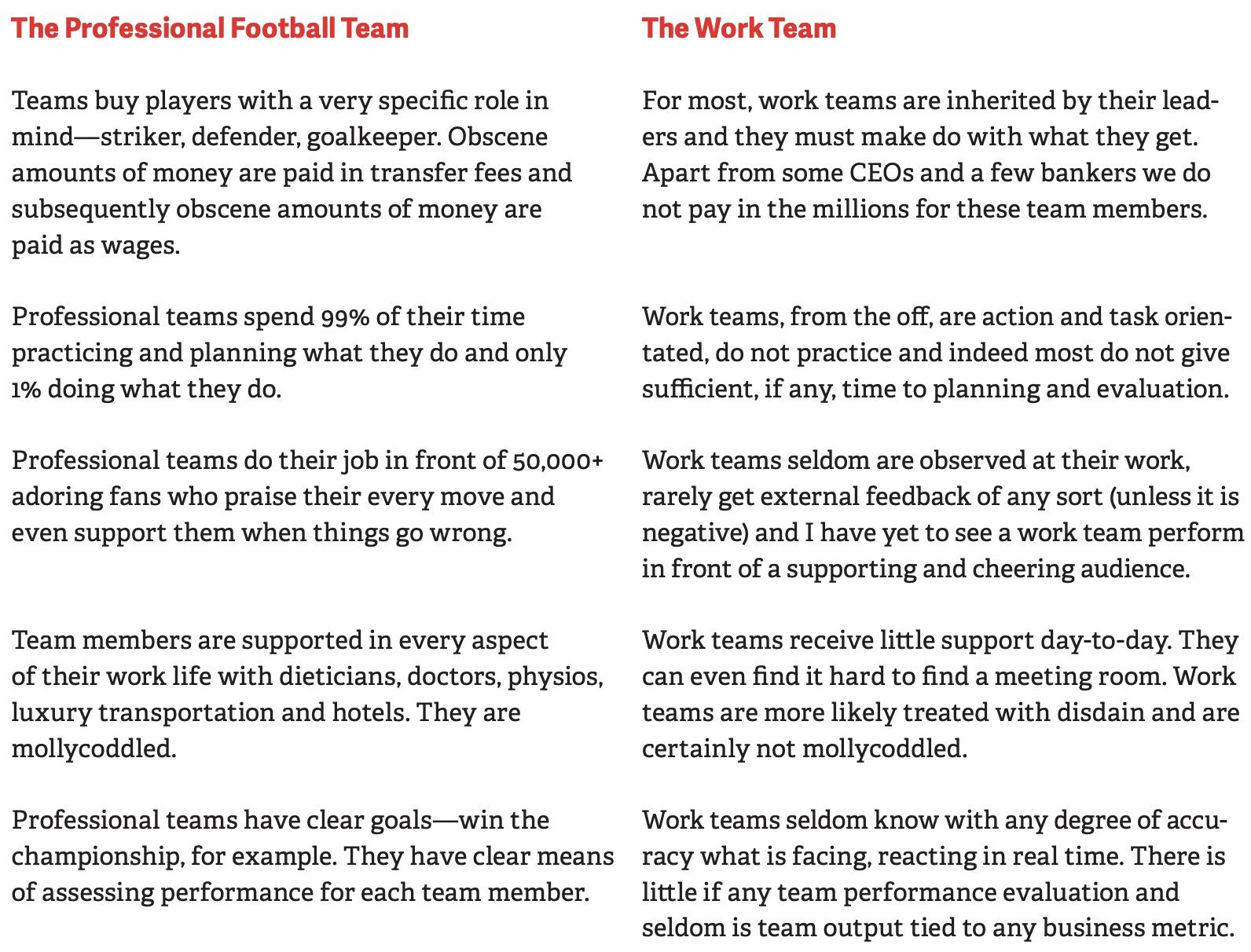

There is no comparison to be made between a professional sports team and a work team. They exist in two entirely different realms. Just consider the difference between a professional football team and a work team.

If you want to persist in making comparisons between work teams and sports teams I recommend that you go to your local park on a Saturday morning and observe the ‘under nines’ football team in action. The chaos, the disorganisation and the sight of 20 players chasing the ball at the same time in one corner of the field is far more representative of a work team than any professional team comparison. Stop using sports analogies. They make no sense.

3. Team Development Is Only for Problem Teams

No, it is not. Every team regardless of level, composition, and seniority (yes even the CEO and their team) can be better than they are today. Every team has room for improvement, but they must give time for reflection away from the day-to-day on a regular basis to think about “how” they do “what” they do. This is one big attitude change required in all organizations. There must be scheduled and structured time to think about these issues. How else can a team be expected to improve effectiveness—anything else is just hit and miss and a wing and a prayer! The organization has to make this an imperative, a must do, and not allow it to be optional or accept the age-old excuse of “not enough time.” The team that reflects and gives quality time to this practice will be far more efficient and effective, will indeed save time compared to the team that does not or will not.

Team development is perceived as something that one does for the failing team, the team in trouble. The smart organization will recognise that all teams need to commit time to their own development. Failure to recognise this is a failure of strategy and ultimately a failure of leadership. It is time to re-think the attitude to teams.

4. Harmony Is Essential—Conflict Is Anathema

Conflict is not the issue, it is how the conflict is managed that causes problems. Conflict is essential in a team. It is the source of innovation. Imagine the team that does not argue, debate, and disagree at times. What hope have they ever to innovate, to find better ways to do things, to address problems and failures? How can a team possibly learn together it they do not have conflict? The team without conflict is a very ineffectual team, and a very boring team at that.

Appreciate the fact that harmony is nice to have, but conflict is essential. How you manage conflict is the critical element. Conflict can never be allowed to become personalized. There must be rules of engagement. There must be someone (normally the leader) acting as a facilitator to ensure that all ideas, disagreements, and debates are encouraged and resolved to the benefit of the team moving forward. If you have a team that exists in perfect harmony you had better create some conflict or the team will soon be going nowhere. It is the conflict of ideas, approaches, and solutions that matter most. Personal conflict, on the other hand, is anathema and must be quickly eradicated.

Create that argument, embrace those differences, ensure that all team members can ask questions and offer their ideas and thoughts. Make psychological safety a prerequisite for all teams and support your leaders to deliver this environment.

5. Organizations and Senior Leaders are Champions of Teamwork

The rhetoric of organizations and senior leaders tends to indicate they are champions of teamwork. The reality, however, points to a very different scenario.

I have yet to find an organization with a real, genuine team strategy. Strategies for everything else, but none for teams.

Teamwork does not happen by accident. The organization, for most, operates through teams yet all the systems and processes are designed for the individual—recruitment, compensation, performance management, and general support. The disposition of most organizations would suggest they believe in magic, and just by calling a group of people a team they will become high performing. For teams to work and a real return to be realized, an organization must put a corporate team strategy in place. Anything less is to suggest that they do not believe in the power of teams.

Teamwork does not happen by magic. Nice words and values do not deliver effective teams. The day of the truly empowered team has arrived. Unfortunately, despite the rhetoric, organizations and senior leaders are not the champions of teamwork they need to be. Organizations and senior leaders need to get their act together.

6. Team Types and Differences

Most organizations cannot tell you how many teams they have in play. They have no idea as to the number of each type they have—traditional, project, teaming work group, or virtual teams. There is little recognition that different teams require different approaches to recruitment and composition. The virtual team requires very different types of people in terms of membership than the traditional team. Indeed, the means to team management for a virtual team is radically different than that of a traditional team. All team types have strengths and weaknesses, and all have different challenges. Yet, no strategy exists to deal with these differences. No standards established as a minimum requirement for an effective team and equally no metrics in place to understand what constitutes success for a team in an organization.

If teamwork is that important, every organization should at least know the basics.

7. Team Size

There is substantial evidence that team size has a very great impact on the effectiveness of a team in a work context.

The issue of team size is linked to how we define a team and indeed to the way the term “team” is used and understood. The term is applied generically and seems to encompass all group activity and often is used to refer to an entire department and in some instances to an entire company. These larger groups, mistakenly called teams, are in fact comprised of many teams.

The term team should only be used to refer to a real team, that by definition is:

“A group of people, less than ten, that need to work together to achieve a common goal, normally with a single leader and where there is high degree of interdependence between the team members to achieve the goal or goals.”

There are several issues that have been identified when a team is in double digits—social loafing, cognitive limitations, and the communication overhead. These are aside from the issue of larger teams breaking down into sub-teams and the inevitable emergence of cliques which can be very damaging not only to effectiveness and relationships.

Social loafing: People in larger teams perform less well than those in smaller teams. Larger teams allow for the concept of social loafing as accountability lessens and people feel less responsibility. The larger team will always carry passengers, and this can have a very negative impact for all concerned. This is apart from the fact it is simply not a good use of people resources.

Cognitive limitations: There was a limit to the number of individuals with whom any one person can maintain stable relationships. Once this number moves into double digits it becomes more and more difficult to maintain these relationships and demands on our time and effort in maintaining them impacts our effectiveness for the task at hand.

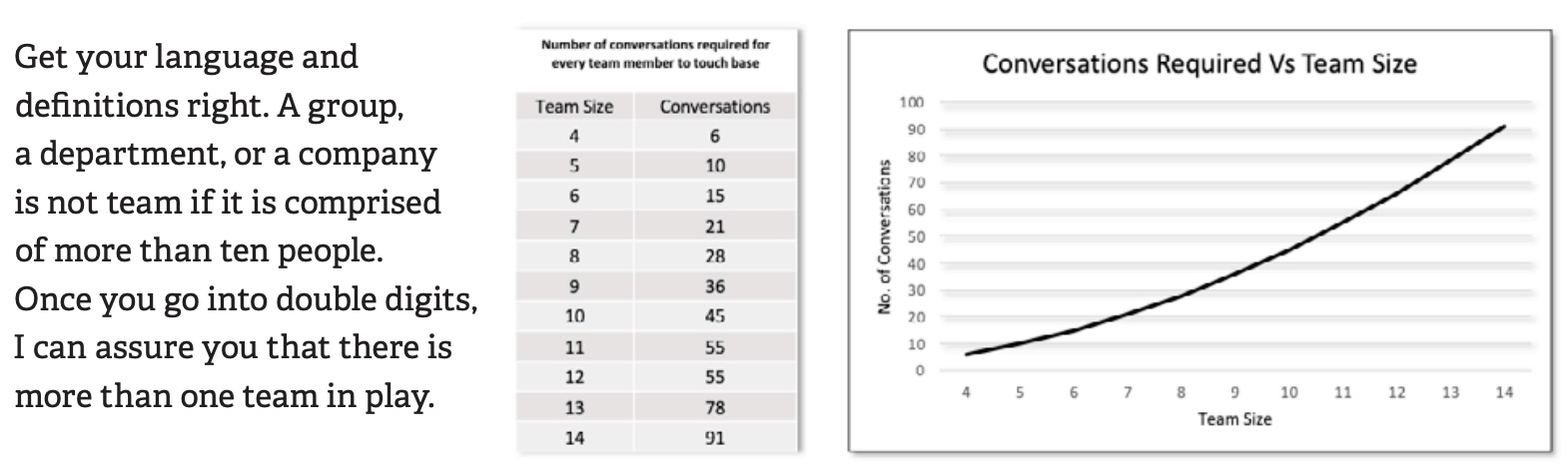

Communication overhead: The more members in a team, the more communication channels required to keep the team informed. A team of five people require 10 conversations to be fully connected and informed. This rises to 45 for a team of 10 and 91 for a team of 14. The following chart demonstrates the exponential rise in communication channels required as the team increases in membership. The reality of the situation is simply that larger teams will not be able to manage or complete the communication required.

The Need for Strategy

With these myths of teamwork and misconceptions (and there are many more) out of the way, what is meant by corporate team strategy (CTS)? Delivering a strategy for teams is a means to ensure that high performing teams are the rule and not the exception. It is a means to ensure that. as an organization, a network of teams can be delivered. The day of the lone wolf is over, and teamwork and the network of teams is the means to competitive advantage and agile capability. There is the big change in attitude required. Time and money must be invested, and it must be recognised that teamwork does not happen by magic or chance—the disposition of most organizations today.

CTS is a strategy separate to all other people strategies. It is about understanding what, why, and how teams are deployed into the organization and how they are supported. It is about understanding the difference between team types—Traditional, Project, Teaming Work Groups (TWGs), and Virtual Teams. It is about how you select for teams.

CTS is about deploying a team assessment methodology and team model that creates an environment for reflexivity for teams and creates a structured means for teams to self-assess and make improvements at the team level. It is about creating time and supported space for teams to regularly meet to consider their modus operandi. It is about understanding what constitutes good teamwork, what is successful teamwork, and setting the benchmark not just in performance terms but in terms of minimum standards for teams.

CTS seeks to identify the key business metrics that are impacted by teamwork and can be correlated with a team measure to indicate successful or failing teams in such a way that intervention can happen at the earliest possible moment for a team in trouble. CTS can also determine the best approach for team-based assessment integrated with individual performance management.

For too long the assumption has existed that teamwork just happens, that we are all naturals when it comes to teamwork. Interventions are for failing teams, when a team gets into trouble. We must accept that all teams can be more effective than they are today. Anything we do for teams must be for all teams and not just a few, from the CEO and their team to every team in the organization.

To do this means developing a CTS, identifying a tool and methodology that supports the team to self-serve their development. CTS draws support from the Organizational Development function, but with solutions that are specifically geared and designed to suit the team environment. Whilst inter-dependent with other people strategies, successful CTS aims for the selfsufficiency of teams in improving their own effectiveness. Most teams, if they are given the time to be reflective, given a reliable, robust, and proven methodology will improve themselves. Research has demonstrated that teams that are reflective are the teams that are innovative.

To begin the process of developing a CTS, the following are some of the questions that must be answered. Most organizations will not be able to answer these questions without detailed research. If a team-based organization is what one wants, then these answers are essential. Developing the strategies, processes, and programs to deliver on these concerns is what ultimately delivers a CTS.

Questions to Be Addressed In Formulating a CTS

- How important is teamwork in our organization?

- Are employees engaged in more than one team at a time?

- How many teams do we have at any one time?

- How many team types do we have at any one time—Traditional, Project, TWGs, Virtual, committee?

- What is the optimal team size in terms of team type?

- When do we deploy these different types of teams?

- What is our model for teamwork?

- What is our language of teams/teaming?

- What tools do we provide to support our teams?

- What kind of leadership do these different teams need?

- Are there differences in performance between teams?

- Is there a team that demonstrates the ideal for our organization?

- What teamwork behaviors do we expect?

- How do we measure team success?

- Is there a means of assessment?

- How often do we assess teams?

- How often do teams assess their own effectiveness?

- Is teamwork performance integrated with individual performance?

- What training do we provide for team members and leaders?

- Who do teams turn to when they need help?

As one develops a CTS, one is impacting the culture of the organization. As a CTS develops in content and sophistication over time, so does “the way we do things around here.” The culture changes from a traditional hierarchy to a team-based teaming culture. The organization is redesigning itself.

It is not easy. It takes time, effort, expertise, and budget, but it is not rocket science.

Despite the increase in HR spend globally on systems and technology, despite the overall spend and ever-increasing deployment of new technology, business productivity has not grown or kept pace. Growth in business productivity is at its lowest since the 1970s. I suggest this is, in part, because we are imposing technology on organizations to deliver something that the traditional hierarchy cannot do. It is like putting wings on the family car and assuming it can fly!

When the strategy is in place, when there is a proven methodology and tools to support the teams, when reflexivity is a reality, team effectiveness will improve, innovation will increase, and team morale and motivation will continue to build, and a safe psychological environment will be established. Then, new technologies can have a real impact on productivity and will be fit for purpose, as will the overall design of the organization and the emerging culture. The traditional hierarchy has had its day. The new organization is arriving—a network of teams— and a focus on developing a CTS is a big step on the way to delivering that new world.

There is, without doubt, a need to change the attitude towards teams. Teamwork is so important organizations must now treat team performance as a strategic imperative. It is time to stop muddling on with poorly performing teams and accepting mediocracy. There needs to be a big attitude change and it needs to be now.

It is truly time to wake up and smell the coffee!