Innovate Where You Differentiate

Silicon Valley startup Homejoy seemed destined for success.

It offered a platform connecting customers with professional cleaners in 35 cities across the US, Canada, the UK, and Germany. With a first-time cleaning price of nineteen dollars, compared to competitors’ eighty dollars, Homejoy quickly grew its customer base to 1.5 million and raised $40 million in funding.

With this funding, Homejoy ambitiously expanded beyond cleaning to offer other home services like plumbing and handyman work, aiming to boost revenue opportunities with existing customers. It was, seemingly, a winning strategy.

But as it turns out, this strategy was a complete disaster.

THE RISKS OF PREMATURE PIVOTING

Although Homejoy’s competitive price point attracted many customers, fewer than 20 percent returned for repeat services. Poor retention combined with high acquisition costs resulted in reduced profit margins.

They also struggled to retain a stable cleaner workforce, which exacerbated the problem. Many left to seek better opportunities or were dissatisfied with Homejoy’s policies, including low pay, unreliable scheduling, and lack of support.

Expanding into additional home services only added to Homejoy’s difficulties. The move diluted the company’s energy and negatively impacted delivery quality. Managing diverse services required more resources and expertise than Homejoy had. Recruiting, training, supporting a varied workforce, and navigating complex logistics and regulations proved too demanding.

These core issues of low worker and customer retention remained unresolved.

Ultimately, Homejoy’s attempts to diversify and expand geographically distracted from its core problems. Due to poor decision-making, its low-cost strategy was unsustainable. In July 2015, just five years after its launch, Homejoy shut down.

The Homejoy story highlights the dangers of lacking a viable differentiator before making strategic pivots. Branching into new areas overshadowed the weakness of their core business. Introducing more change hastened their decline as the company lost focus on what truly mattered. As a result, they lacked a stable footing on which to base these shifts.

THE POWER OF THE PLANTED FOOT

Imagine a basketball player performing a pivot. All eyes are focused on the foot moving in circles. It’s about the change in direction, the movement. Just like in basketball, when we think of a pivot in business, we focus on the changes we must make. What shifts do we need to undertake?

But most people don’t realize that when executing a pivot in basketball, there is a foot firmly planted on the ground—one that doesn’t move—one that provides a solid foundation for the necessary change.

Although all eyes are on the foot that is moving, the unsung hero is the planted foot. It provides a solid foundation and the stability needed for effective pivots in both basketball and business.

Homejoy pivoted without having stability. Consequently, their changes and expansion were built on quicksand.

In a world of uncertainty, chaos, and bright shiny objects, knowing where to plant your foot is critical to providing stability, clarity, and sanity in an ever-changing environment. Understanding where to deepen your investments will give you leverage.

The key is to innovate where you differentiate.

TARGETING YOUR INNOVATION EFFORTS

The challenge for most organizations is to determine what’s most important. If you try to be the best at everything, you will be great at nothing. Therefore, knowing where to double down and when to cut back your investment is crucial.

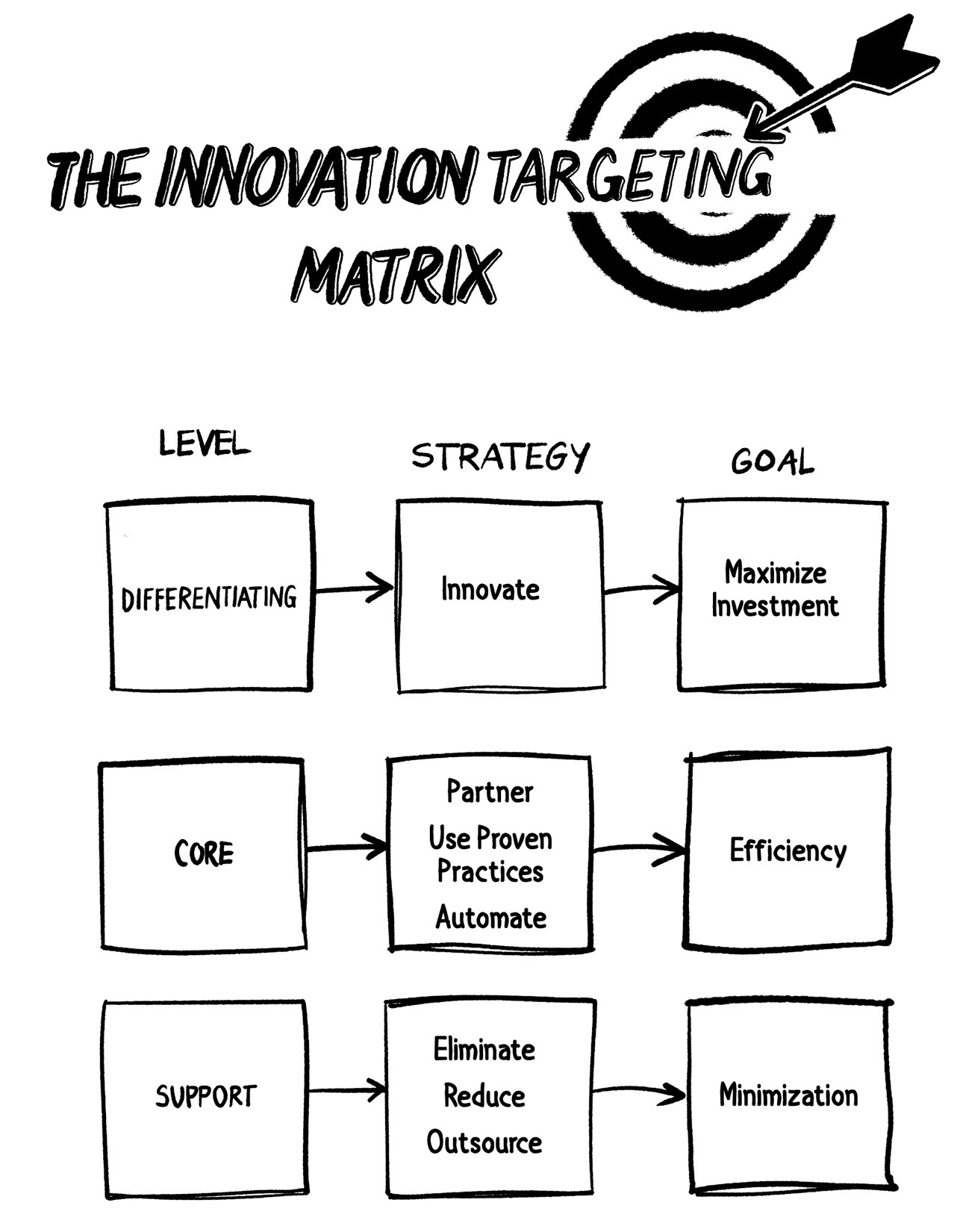

To help you decide on the appropriate strategies for your activities, consider the Innovation Targeting Matrix (ITM). This framework categorizes business activities into three levels: support, core, and differentiating. What constitutes support, core, and differentiating varies from company to company.

SUPPORT ACTIVITIES | Support activities are essential for running a business, yet they do not create direct customer value. Because of this, you ideally want to find ways to eliminate, minimize, delegate, or outsource these tasks.

Payroll is an example of a common support activity. Unless handling payroll is your differentiator, it’s not profitable to build custom solutions but instead outsource this function to a specialized company. Similarly, many meetings are a support activity and are often unnecessary, wasting time and resources.

If it doesn’t create external value, your goal should be to keep costs to a minimum and avoid this work becoming a distraction.

CORE ACTIVITIES | These activities create direct customer value but are not your key source of competitive advantage. They are, to use a gambling term, only table stakes—the entry cost, not the reason someone will do business with you. However, if you get them wrong, it might be a reason customers leave you for a competitor.

In a hotel for example, providing working Wi-Fi, a clean room, and food options are often core activities. No one chooses a hotel for these reasons. But if there is a problem with any of them, the odds are your guests won’t stay with you again.

Core work needs to be a well-oiled machine—cost-effective with high-quality levels. Errors will lead to lost customers. Although your approach to these activities doesn’t need to be unique or distinctive, you need to excel. Therefore, your primary strategies are to simplify, automate, use proven practices, and develop strategic partnerships.

DIFFERENTIATING ACTIVITIES | Differentiating activities are those that set you apart from your competition. They are why someone chooses to do business with you, not someone else. These are your most important capabilities and require the most attention. Differentiators are rarely a product or service and are specific to each company.

Although Radio Flyer is known for its iconic “The Original Little Red Wagon,” their differentiator is a feeling. When Robert Pasin, the company’s CEO, asks customers about the brand rather than the product, people respond with smiles and stories of wagons as race cars, rockets, spaceships, submarines, motorboats, or magic carpets. What makes Radio Flyer special isn’t their wagon but their ability to, in their words, “bring smiles and create warm memories that last a lifetime.” This is an irreplaceable differentiator built on emotion.

You should make the greatest investment in differentiating work because this is what your customers value most about you. Ensure you get this right and focus on these areas. Empower workers to deliver non-cookie-cutter results that will continually set you apart from your competitors.

It’s important to note that your differentiator is not a department, function, or role. Every person in every department can and should contribute to it. Equally important is that your differentiator is not a product, service, or offering. It is a set of capabilities that helps you distinguish yourself in a crowded market and will stand the test of time.

Your main strategy is to leverage your differentiating capabilities to create unique and valuable solutions while using other strategies for support and core business.

AVOID INVESTING TOO MUCH IN CORE

Most companies understand that they should not invest heavily in custom solutions for support capabilities, but confusion arises with core versus differentiating activities. Based on twenty years of using the Innovation Targeting Matrix, on average, most organizations spend only 20 to 30 percent on differentiating investments and 70 to 80 percent on core.

To double your impact in critical business areas, use different strategies for core activities and focus on differentiating investments.

Shift from 80 percent core and 20 percent differentiating to 60 percent core and 40 percent differentiating. Reallocating twenty percentage points from core to differentiating will double your investments in differentiating without spending extra money.

An example of leveraging someone else’s differentiator to improve your core can be seen in CCC, which develops and manages insurance claim processing technology for many major automotive insurance companies. Although these systems need to work flawlessly, it wouldn’t be economical for insurance companies to develop their own custom systems in-house. In most cases, claims processing is not the reason customers do business with insurance companies; it’s only a core activity.

However, this automotive claim processing technology is differentiating for CCC. Their premium software is used in over 25,000 of the 40,000 collision repair shops in the United States. To focus on their own differentiators, the large insurance companies realized that they needed to partner with CCC for this core work. Handling these tasks internally could distract them from their unique value propositions. By concentrating on what sets them apart, they gain both leverage and stability.

USE YOUR DIFFERENTIATOR EVERYWHERE

The Innovation Targeting Matrix is not only valuable at the enterprise level but also within each team or department.

During my Accenture days, I was actively involved in training other consultants on process and innovation methodologies. We spent millions of dollars developing training programs, yet we never really knew if we were getting the biggest bang for our buck. Traditionally, a “gut feel” strategy was used to determine where training dollars were spent.

Given this problem, we decided to use the ITM within our training organization. This enabled the company to reevaluate the curriculum and ensure investments were focused on getting the greatest value for money.

When used for training, we modified the terms slightly to fit our needs. “Differentiating” skills (and the associated training programs) were those necessary to beat the competition. These represented our special sauce. “Core” consulting skills created great value but were not unique to us. “Support” meant that the skill was commonplace and enabled the delivery.

The goal was to match the investment to the value it provided. The strategies for training and development included the following:

-

Support: Completely outsource, leveraging public-domain and off-the-shelf training modules. This required less investment and, more importantly, limited time and resources.

-

Core: Design and partner with world-class training organizations to provide tailored versions of existing training.

-

Differentiating: Design, build, and deliver high-value proprietary courses in-house with the help of internal thought leaders.

When the training courses were mapped on the ITM, everyone quickly realized that most of the investment money and resources had typically gone to the internal development of lower-value public domain knowledge training, often targeting thousands of newer hires or younger consultants. Sometimes, as in this case, it is easy to confuse volume with value.

These fundamental courses were important but not a primary business advantage.

Therefore, instead of custom-building training for basic programming and functional skills, we outsourced most of these services to a third party with vast libraries of videos on the topics. This provided huge cost savings and allowed us to devote our internal resources to programs of higher, unique value, such as courses that relied on proprietary content.

These high-value courses were created by a small group of experts in their spare time. Because these skills were rare, it was difficult to tap into these resources to build the training. However, developing quality courses was critical, as this created differentiating value.

Because there were typically no externally available options for these specialized topics, the solution was to partner the content experts with instructional designers. This allowed the experts to narrowly focus on their area of specialization while leveraging others to create the courses.

As you can imagine, the insight gained from this analysis rapidly shifted investments, and the appropriate strategies were used for each training course.

While many might view training as support in nature, like all functions, it encompasses activities from all three levels, support, core, and differentiating. Equally, functions that might appear to be differentiating—such as sales—will have support and core activities.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND THE INNOVATION TARGETING MATRIX

Over the past couple of years, the allure and potential of artificial intelligence (AI) have stirred considerable excitement and apprehension across the business landscape. Organizations are grappling with AI’s dual nature: It represents a remarkable opportunity to redefine operational paradigms, yet it also poses the risk of obsolescence for those slow to adapt, potentially leading to job displacement or competitive disadvantage.

Given AI’s power, its influence on your organization cannot be overstated. However, a critical question to consider is where it fits within the ITM. Should AI become a centerpiece of your organization? Is it a differentiator? For most organizations, it is not. Unless your business specializes in AI as a distinguishing feature, AI is most likely core.

In today’s digital economy, integrating AI within your business operations is no longer optional; it’s a fundamental requirement. This is the definition of core. It’s table stakes. It’s the cost of entry. And the stakes will keep increasing over time. It is not about a one-time adoption of AI; it requires continuous enhancement of these capabilities.

AI technologies are instrumental in improving all three levels of activities: support, core, and differentiation. Nevertheless, aspiring to be the leader in AI innovation can be misguided for non-AI-centric companies. This pursuit could distract you from focusing on areas where your organization can truly differentiate and deliver unique value.

Given this, the best strategy for most organizations is to partner with a company that specializes in AI and has it as their differentiator. The key is to make sure AI does not become a bright, shiny object for your organization that diverts your attention from what matters most.

CREATING STABILITY IN AN UNCERTAIN WORLD

In a world overflowing with opportunities and distractions, distinguishing between the two is essential. Focusing on where you should concentrate, rather than chasing the next fleeting opportunity, is critical. This strategy enables you to build a solid foundation for innovation, keeping your planted foot firmly on the ground.

As a business leader, now is the time to take decisive action. Evaluate your current strategies and determine where you can apply the Innovation Targeting Matrix (ITM) to make the most impactful changes. Start by identifying your support, core, and differentiating activities. Redirect resources from support and core activities to center on what truly sets your business apart.

Don’t wait for the next disruption to force a reactive pivot. Proactively innovate where you differentiate and secure your place as a market leader. Your planted foot will provide the stability needed for all future pivots, ensuring your business thrives in an era of uncertainty and change.

Adapted from PIVOTAL: Creating Stability in an Uncertain World by Stephen M. Shapiro, published by Amplify Publishing Group. Copyright © 2024 by Stephen M. Shapiro.