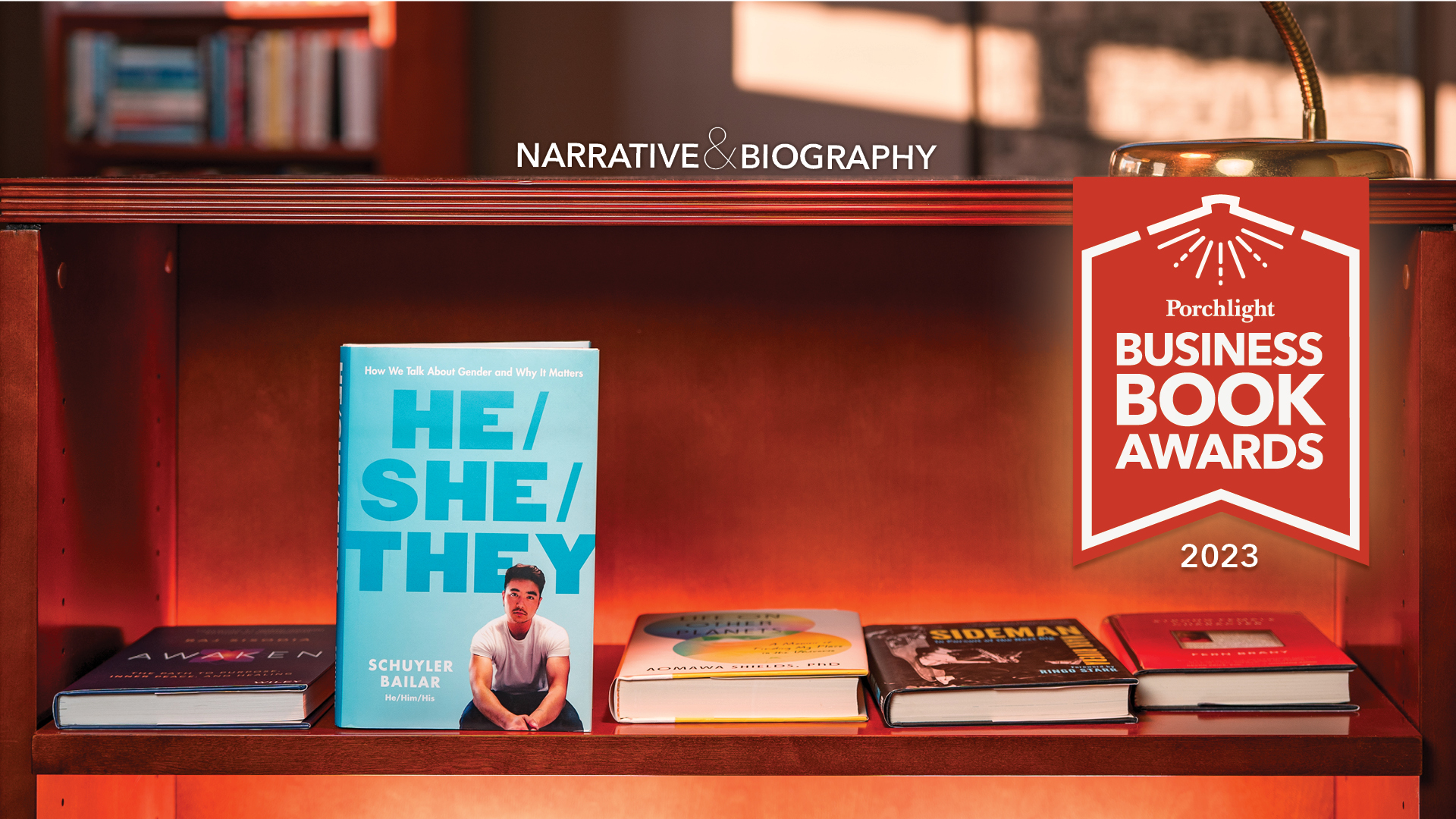

He/She/They | An Excerpt from the Narrative & Biography Category

We walk out one at a time, in alphabetical order. My last name begins with B, so I am first. I can feel my heart beating in my ears, the sound held inside my head by my silicone cap. A little echo chamber.

“From Washington, DC, freshman Schuyler Bailar,” the announcer booms.

I know everyone is watching me. I know I’ve done this on a thousand occasions before. But this time is different.

Underneath my crimson warm-ups, there is no longer a one-piece swimsuit that women usually wear. Instead, I am wearing a tiny little Speedo. I am now on the men’s team.

Hundreds of articles have been published about my switching from the women’s to the men’s team. “Transgender swimmer,” they all write. Some attack me for my history, saying I’ll never be a real man. Others say my history of an eating disorder just means I am a “deluded woman with body issues.” Many claim there is no way I could keep up with, much less beat, other men. “From beautiful competitive woman to mediocre ugly man,” one commenter wrote on a national profile about me.

As I stand by the edge of the pool waiting for the rest of my teammates to join me, I am fifteen again, standing in my women’s swimsuit behind the blocks with three girls from my relay. I remember the confidence, the feeling of knowing I could do exactly what I had set out to do. I remember the rush of the natatorium going silent as I put my hand over my heart—my pre-meet ritual—my fingers and thumb straddling my swimsuit strap on my shoulder. I had done this at the start of every single meet during the singing of the national anthem. I remember staring out at the pool as the music ended, and I took a deep breath, imagining my final stroke of my race.

I take a deep breath now, staring out at the pool as a D1 college swimmer. Everything feels so different. I’ve never stood alongside thirty-eight college guys before. I’m at a pool I’ve never raced in. And it feels like all eyes are on me. But, as always, the water resembles beautiful blue glass and I breathe a sigh of relief.

This is different, but it is also the same. The same twenty-five-yard pool. The same hundred-yard breaststroke race. The same breaststroke I have done since before I can remember. The same echoing acoustics that make hearing so difficult. The same chlorinated air that makes everyone cough. The same “Take your mark—boop!” before we launch off the blocks. It’s all the same.

When the team is gathered along the edge of the pool, the natatorium silences. We stand in identical clothing, and the anticipation dances in my fingertips. When I am this nervous, the most nervous, I imagine my blood is rushing through my veins like white-water rapids.

When “The Star-Spangled Banner” begins to play, I instinctively begin my pre-meet ritual. But this time, my fingers seeking my shoulder strap find nothing. In that moment, I realize that while everything is the same, it is also brand new. For the first time in my life, I am competing as just myself—without the baggage of who everybody told me to be, who everybody said I was, who I thought I was supposed to be.

Today, I am just who I am. I am Schuyler.

My eyes well with tears. More than nineteen years of stumbling to get here. Just a few months ago, I was ready to quit swimming. A year ago, I was ready to quit the world and life altogether. But today, I am standing tall, a proud Korean American queer transgender swimmer on Harvard Men’s Swim and Dive—the first openly transgender athlete to compete for any D1 men’s team in the NCAA.

Of course, surviving my first meet (and not getting last) did not mean that everything was easy from then on. It would take my teammates the rest of the year to consistently gender me correctly. It would take me nearly three years to feel comfortable around them. And all the years since I came out are still not enough to dispel all the hatred and bigotry about transgender people, especially in athletics.

Over the next four years, I not only became the first—and, at the time, only—transgender athlete to have competed for the team that aligns with their gender identity for all four collegiate seasons, but I also became a well-respected educator on transgender inclusion.

I never knew where this journey would take me when I began. The first speech I gave was at my own high school. The night before, I was awake until two or three in the morning, attempting to write the speech itself. Dozens of drafts in the trash, I had no idea what other people would want from me. What should I tell them? What could they learn from me? That speech was better received than I’d expected. Some students even said it was the best assembly they’d experienced. So, as word spread, one speech led to another. By sophomore year, speaking was the primary way I spent my free time. By graduation, 102 speeches were in the books.

Despite regular assurances that what I had to say was valuable to others, I often found myself perplexed over why people wanted to listen. I was just a college kid who wanted to swim. When news outlets would call me an “advocate” or “activist,” I used to tell them no.

“You only think that I am an activist,” I insisted, “because I am a transgender swimmer, and I’m talking about it.”

Before every single speech, I wondered to myself, Why are they here? Why do they care? Only rarely, the answer was clear: I was talking to a group of swimmers or transgender folks like me; we were comrades. But most of the time, I spoke to people with whom I had little to nothing in common, or so it appeared. I tried to imagine the perspectives of the audience members—the students, coaches, administrators, teachers, mental health professionals, medical providers, or employees at a bank … How could I connect with them? Because, in the end, the inability to connect is what breeds hatred and bigotry. That is, connection is the essence of our humanity itself.

Excerpted from He/She/They: How We Talk about Gender and Why It Matters. Copyright © 2023 by Schuyler Bailar. Reprinted with permission from Hachette Go. All rights reserved.