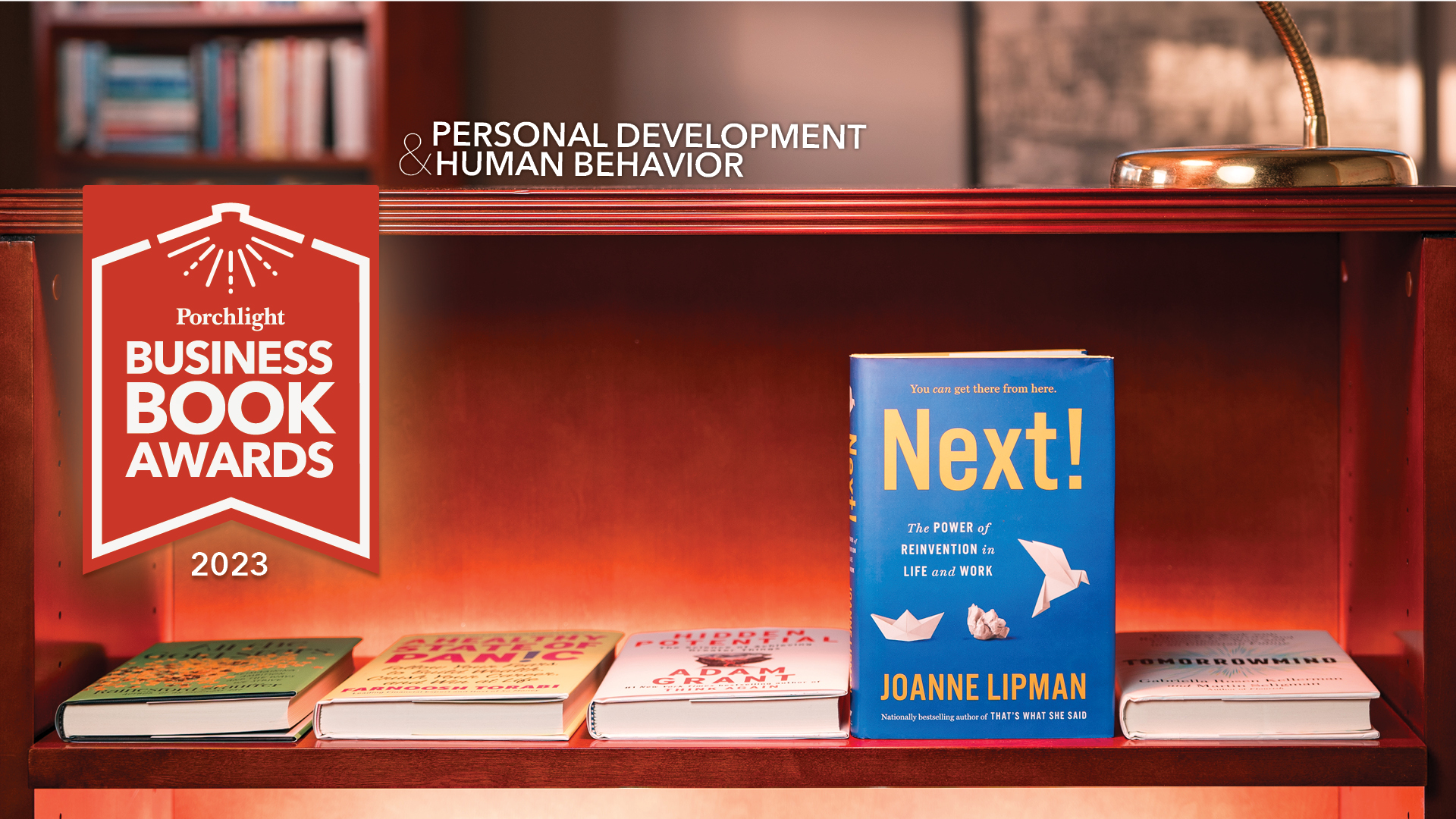

Next | An Excerpt from the Personal Development & Human Behavior Category

Porchlight Creative Director Gabbi Cisneros writes of Joanne Lipman's Next! that:

Lipman lets the stories of individuals’ career searches, struggles, stops, and solutions play out, making each story as educational as it is engaging. I silently cheered on each subject as they, at fifty or fifteen or anywhere in between, had their own coming-of-age moments of clarity. Each example has the storybook ending we hope for, the kind that is an exciting new beginning, and Lipman narrates the journey to that point clearly and analytically, but with an appropriate emotional edge.

The following excerpt is from the book's Introduction.

When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up? I was going to be a spy. Starting at age seven, I carried around a black-and-white-marbled composition notebook, just like the heroine of my favorite book, Harriet the Spy, jotting down overheard conversations at school and secretly listening in on my big sister’s phone calls with her boyfriend. After I read Little Women, I decided I would still be a spy, but I was also going to be a novelist like Louisa May Alcott. Then I read a delightfully gory book called The Bog People, about the discovery of pickled Iron Age corpses in a Danish bog, and added archaeologist to my multi-hyphenate future.

I ended up, of course, being none of those things. But like me, most kids easily envision all sorts of different paths for themselves. They have no trouble flitting from dreams of rock stardom to fantasies of curing cancer. Nor does it bother them when they give up a future identity; they simply try on a new one. In a 2020 survey, when more than two thousand adults were asked what they had wanted to be as children, the most popular answer was professional athlete; other top picks were astronaut and actor. In reality, almost 80 percent of them landed in different careers than the ones they’d envisioned. (That’s hardly surprising, given that, for instance, only three out of every ten thousand boys who play high school basketball will ever make it to the NBA.)

Kids easily cycle through different ideas of who they want to be. They discard and try on new identities with ease. Their envisioning of future possible selves isn’t just about careers. They don’t just imagine what they want to be when they grow up, what careers they might want, like firefighter or ballerina. They invent and discard fantasies of all the things they want to do and how they plan to live. When I was in grade school, on my bulletin board in my childhood bedroom I tacked up a list of twenty things I wanted to accomplish before I turned twenty. That piece of lined notebook paper is lost to the dustbin of history, but I remember a few of my top choices. Bicycle across the country. Publish a best-selling novel. Canoe through the Canadian wilderness—never mind that the only time I’d been in a canoe was during two weeks of Girl Scout camp. (And no, I didn’t accomplish any of those things either.)

But somehow, along the road to adulthood, we lose the power to reimagine different futures. In college we are steered toward a major. Then, if we’re lucky, we get a job. Maybe we get married, have kids, settle down, buy a home. Pretty soon it seems as if our choices have narrowed. Job, career, where we live, what we do in our free time, how we take our coffee. Changing one element means upending the others. We’ve gotten accustomed to a certain way of life, or income level, or professional status. It’s hard to switch gears. And before you know it, without realizing it, it seems impossible to really change. We’ve bet on the life we have, and it’s too hard to think about the life we don’t have. We have invested in our current path, and we double down instead of reevaluating. “We don’t let go of anything important until we have exhausted all the possible ways that we might keep holding on to it,” as William Bridges wrote in his book The Way of Transition.

For millions of us, that sense of complacency was shattered with the Covid-19 pandemic. The crisis jolted us out of our routines and sparked a collective reckoning, one exacerbated by economic uncertainty and political unrest. We reprioritized our lives and reordered how we envisioned the future. Businesses, blindsided by events, furiously attempted to pivot. Leaders were forced to rethink their roles and recalibrate their approaches. Today almost all of us are still struggling to adapt to this quickly changing reality. “People have suffered. They’ve been afraid. The ground on which they stand has shifted. Many have been reviewing their lives, thinking not only of ‘what’s important’ or ‘what makes me happy’ but ‘what was I designed to do?’ ” the columnist Peggy Noonan wrote in the Wall Street Journal early on in the pandemic, sharing a sentiment that continues to resonate.

The pandemic changed society in many ways, but among the most consequential has been a rethinking of our relationship to our jobs. Millions quit the workforce in 2021 and 2022, and stunningly, surveys indicate that a third or more of them had no new job lined up to go to. We reevaluated how much time we want to spend at work, where and how we wanted to spend it, and our ideas about what constitutes a “good job” in the first place.

A record number of people didn’t just look to switch jobs but to switch careers entirely. A 2021 Pew survey found that 66 percent of unemployed people at every income level—not just privileged high earners—seriously considered changing occupations. When Indeed, the employment site, surveyed job seekers in 2022, it found that fully 85 percent were looking for new careers outside of their industry.

It was almost unprecedented in modern history, a global reset. But in truth, even without a pandemic, almost everyone goes through this kind of reappraisal at least once in their life—and probably far more than once. The average person switches jobs a dozen times over the course of their working life. You might be fired or downsized out of a job; in my own field, journalism, 30,000 jobs have been wiped out and 2,500 US newspapers have closed amid financial challenges in the last few decades. Maybe you’re no longer satisfied with your career choice and want to pivot to a new one; even before the pandemic—and before “quiet quitting” entered the lexicon—71 percent of millennials weren’t engaged in their work, Gallup found. You may be facing a major personal crisis, like divorce or the death of a loved one. Or you could have been buffeted by external traumas: the pandemic, war, an accident, a natural disaster like a hurricane or earthquake.

Whatever the catalyst, it prompts in us the urgent need to pivot, to ask the question: What’s next—and how do I get there?

That’s a question I’ve been immersed in for most of my adult life. As a reporter, I covered transformations in business and society; as an editor-in-chief charged with reimagining news organizations in a digital age, I’ve helped lead them. As an author and advocate for gender equity, I’ve worked with organizations as they try to refashion their cultures. I’ve long been intrigued by the challenge of finding the “white space” of opportunity, where new ideas can flourish. There’s no greater thrill than recognizing fresh opportunities that are right in front of your face, yet that others are too preoccupied to see. Ideas that, once you recognize them, spark that smack-the-forehead “aha!” moment. But while I’ve reported on, led, and lived through pivotal moments—both for better (like founding a new magazine) and for worse (seeing that magazine die)—I mostly did so by instinct, by feeling my way like a blind person. That’s what most of us do. There was no guidebook to show the way.

Excerpted from Next!: The Power of Reinvention in Life and Work.

Reprinted by permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Copyright © 2023 by Joanne Lipman.

All rights reserved.