An Excerpt from Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms

The shocks and crises of recent years—pandemic, recession, inflation, war—have forced executives and investors to recognize that the macroeconomy is now a risk to be actively managed. Yet unreliable forecasting, pervasive doomsaying, and whipsawing data severely hamper the task of decoding the landscape. Are disruptions transient and ephemeral—or permanent and structural? False alarms are costly traps, but so are true structural changes that go undetected.

The shocks and crises of recent years—pandemic, recession, inflation, war—have forced executives and investors to recognize that the macroeconomy is now a risk to be actively managed. Yet unreliable forecasting, pervasive doomsaying, and whipsawing data severely hamper the task of decoding the landscape. Are disruptions transient and ephemeral—or permanent and structural? False alarms are costly traps, but so are true structural changes that go undetected.

How can leaders avoid these macro traps to make better tactical and strategic decisions?

In Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms, BCG Chief Economist Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak and Senior Economist Paul Swartz provide a fresh and accessible way to assess macroeconomic risk. Casting doubt on conventional model-based thinking, they demonstrate a more powerful approach to building sound macroeconomic judgment. Using incisive analysis built upon frameworks, historical context, and structural narratives—what they call "economic eclecticism"—the book empowers readers with the durable skills to assess continuously evolving risks in the real economy, the financial system, and the geopolitical arena.

Moreover, the authors' more nuanced approach reveals that the all-too-common narratives of economic collapse and decline are often false alarms themselves, while the fundamental strengths of our current "era of tightness" become visible.

With rational optimism rather than gloom, Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms speaks to the key financial and macroeconomic controversies that define our times—and provides a compass for navigating the global economy. Rather than relying on blinking dashboards or flashy headlines, leaders can and should judge macroeconomic risks for themselves.

The following excerpt come from Chapter 17: After the Convergence Bubble.

◊◊◊◊◊

Using History Wisely

Why care about history? For those analyzing geopolitics—or macroeconomics—history matters because today’s arrangements are the accumulation of past processes, norms, events, and decisions. There are many famous quips about history, including “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce”; “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes”; and “What is history but a fable agreed upon.”1 One that truly resonates with us is William Faulkner’s: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”2 We’d ask skeptics of history’s value how they would understand any system’s performance under pressure, if not by studying its construction?

But historical narrative is treacherous, as the discussion of the convergence bubble demonstrates throughout this chapter. There are two competing mindsets, and both are traps.

The history-is-history mindset analytically ignores the past’s relevance. The mindset can be willful and conscious—even leading professional historians occasionally to see the past as over—or it can be the result of ignorance or agnosticism.3 The outcome is similar: the past has been superseded by new sets of beliefs, rules, drivers, and dynamics. The history-is-history mindset lends itself to imagining new futures, often with unbridled optimism. Frequently, extrapolations are made by those enmeshed in the technological frontier, who argue that innovation will change the rules of the game entirely. Recall that the internet was once touted as a major force of global institutional convergence and freedom. This mindset can be turbo-charged with confirmation bias—the tendency to focus on evidence that confirms prior assumptions, while disregarding evidence that doesn’t. Yet history shapes the present, and history’s path dependencies, influences, and dynamics will continue to matter. As Faulkner said, it is not even past.

The history-is-destiny mindset, by contrast, is a deterministic reading that ascribes to history the role of a predictive machine. Inputs deliver outputs—we are destined to repeat the many grim episodes of the past. This gloomy view holds that doom is predestined and often imminent. And if it hasn’t happened yet, it is only because we are holding on to the edge of a historical cliff.

The popular narrative of Thucydides’s trap—the idea that the rise of an emerging power will inevitably lead to a conflict with the prevailing power—is an illustration of the template-like use of history.4 The concept has made a stunning jump from being a thoughtful if reductive framework (as if all conflicts were the same) to being received wisdom about the inevitability of great-power conflict despite abundant contradictions. Most obviously and simply, the United States and the United Kingdom did not come into conflict as the former colony superseded the former global power in the early 20th century. And let’s not forget that the Soviet Union too was a rising power that sought to displace the United States. But conflict did not happen the way Thucydides’s trap darkly suggested it would. The narrative is still often employed to predict inevitable military conflict between the United States and China—skipping over the fact that the most relevant episodes do not fit the template well.

History is a necessary and powerful instrument for geopolitical analysis. To reject it, or to embrace it too tightly, is risky. Neither a precise map nor a useless artifact, history can provide insight about drivers and context, their relevance reverberating over the long term. But history always risks leading us astray. And that is key to understanding the convergence bubble.

The Rise of the Convergence Bubble

The early 1990s embodied a perfect moment for the history-is-history mindset to take hold of the collective narrative. The end of the Cold War was a unipolar moment set to replace great-power rivalry. It coincided with technological renewal, economic growth, and unbridled optimism about having reached a final form of political and economic governance.

With the system competition of the Cold War over, the history-is-history narrative fastened onto the prospect of global systems convergence. Democracy and liberal market economies were cast as two sides of the same coin, mutually reinforcing their benign, global impacts; individual liberty was seen to underpin both sides of that coin. All societies appeared to be converging toward this democracy-markets-liberty trifecta. Hence the extrapolation toward the convergence bubble.

The convergence bubble comprised four elements.

-

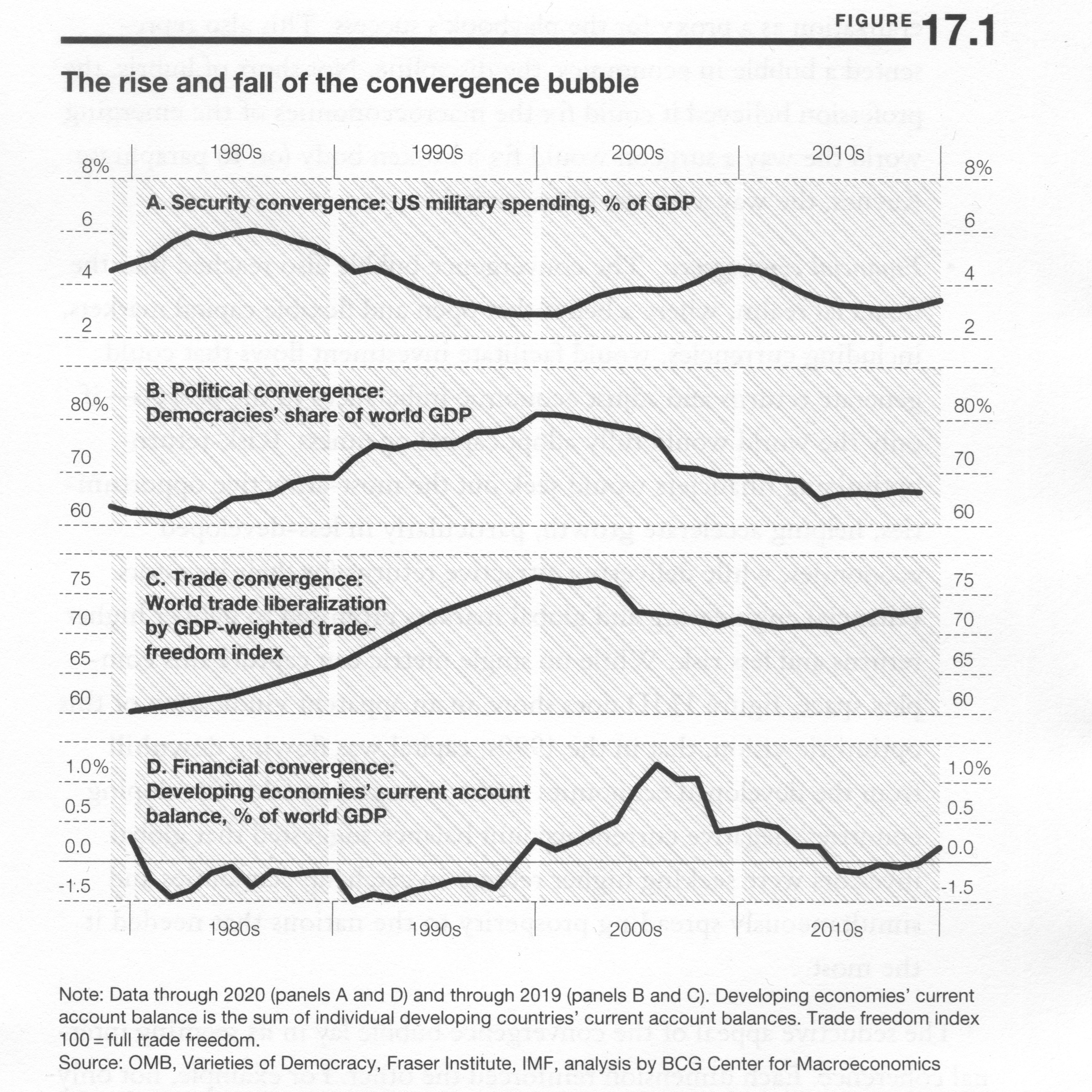

Security convergence. In August 1990, less than a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the world witnessed the Gulf War, a successful, surgical, and multilateral effort to expel Iraq from Kuwait. The sharp contrast with the Cold War’s specter of mutually assured destruction underlined the unipolar moment and fueled bubbly extrapolation toward a future without major military conflict, stabilized by a benign hegemon.5 This relaxation fed through to a decline in US military spending, as seen in figure 17.1A.

-

Political convergence. The end of the Cold War also suggested the end of (political) systems rivalry, and the impending and final victory of democracy. A rise in democratization did follow, as seen in figure 17.1B. These shifts in sovereign governance were underpinned by a loose set of rules for democracy, including political pluralism, freedom of expression, rule of law, and fair elections. And while successes varied locally, global sentiment was bending toward liberal democracy. The advancing and receding tides of political history appeared to have been replaced by a river flowing in one direction.

-

Economic convergence. The rivalry of competing economic systems was also seen as settled, paving the way for convergence toward a neoliberal version of capitalism.6 A polished set of principles emerged to shape new market economies across the globe. Often disseminated through institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, the so-called Washington Consensus offered a playbook for how to get economics right.7 Figure 17.1C shows the degree of global trade liberalization as a proxy for the playbook’s success. This also represented a bubble in economics, the discipline. Not short of hubris, the profession believed it could fix the macroeconomies of the emerging world the way a surgeon would fix a broken body (or, to paraphrase Keynes, the way a dentist fills a cavity).8

- Financial convergence. The convergence bubble also reached into the financial realm, where a belief that open and flexible capital markets, including currencies, would facilitate investment flows that could generate returns and adjust economic imbalances in the process—if only the world would fully adopt capital openness. Risk-return-optimizing financiers would seek out the most-attractive opportunities, helping accelerate growth, particularly in less developed economies, while delivering attractive returns for their investors. Financial engineering and global markets promised to deliver higher returns and less risk. While no single metric can capture this complex space, figure 17.1D does show, in an apparent vindication of this optimistic vision, that in the 1990s, capital was flowing downhill from the developed economies to the emerging world. Developing countries’ negative current account balance suggested that global investors were seeking higher returns in catch-up economies and simultaneously spreading prosperity to the nations that needed it the most.

The seductive appeal of the convergence bubble lays in its seeming internal coherence. Each dimension reinforced the other. For example, not only was free trade going to help growth, but growth would also be an instrument of political convergence to liberal democracy. As former adversaries became wealthy, they would become democratic allies, a rosy narrative that helped the WTO’s enlargement in 2001. The bubble also coincided with the economic boom of the 1990s, when a technology-driven surge in productivity growth promised a new economy. And each dimension pointed away from history, toward a brighter future. Confirmation bias took hold: every data point that confirmed convergence was celebrated, and those that confounded the narrative were seen as anomalous. History was history.

But the convergence bubble, and the rejection of history that helped fuel it, also provided a catalyst for the “arrogance of power.”9 Limited strategic competition caused the United States to mistake a unipolar moment for unfettered and enduring control. Indeed, inside the convergence bubble festered a hegemony bubble. The history-is-history mentality allowed an extrapolation of geopolitical developments well beyond what a view anchored by history would have. It is easy to forget that even in the 1990s, warning signs flashed across the system but were dismissed as aberrations from the new trend. On the security side, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center (1993) and the US embassy in Kenya (1998) foreshadowed the testing of the power of military hegemony to come. On the political side, newly minted democracies lacked the institutional strength to avoid corruption, which augured subsequent disappointments. On the trade side, the Seattle WTO riots of 1999 portended the crumbling consensus around the supposed overwhelming benefits of trade. And on the financial side, the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis demonstrated the risks of contagion and brittleness in a world of ever-greater capital-market integration. The writing was on the wall—history was not even past.

Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review Press. Adapted from SHOCKS, CRISES, AND FALSE ALARMS: How to Assess True Macroeconomic Risk by Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak and Paul Swartz. Copyright 2024 The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce,” Karl Marx; “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” often attributed to Mark Twain; “What is history but a fable agreed upon,” Napoleon Bonaparte but also Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle.

2. William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun (New York: Random House, 1951).

3. With respect to the past being over, in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Francis Fukuyama identified “Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” To be fair, Fukuyama didn’t argue that all significant historical events had ended, but that in the long term, liberal democracy would become only more prevalent. Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992).

4. The term—popularized by Graham Allison—comes from fifth century BC Athenian historian Thucydides’s explanation for the inevitability of the Peloponnesian War: “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” In his 2017 book, Allison says that over the last 500 years, war has broken out in 12 of the 16 cases when a rising power has challenged the established one. Allison suggests that the United States and China may be headed in this direction. Graham Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017).

5. To be clear, convergence does not mean that there wasn’t stress. For example, see the 1995 US intervention in the Bosnian War, the 1990s US involvement in drug wars in Latin America, and a general fear of the threat from nonstate actors. But overall, these were smaller conflicts (at least compared with past wars). In contrast to Fukuyama’s argument for the end of history, Samuel Huntington expected future conflicts to continue, but arising from tribal hatreds and cultural differences. Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996).

6. Gary Gerstle, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

7. The Washington Consensus is an informal set of policy recommendations aimed at promoting economic development in less developed countries. Recommendations include such things as fiscal discipline, trade liberalization, privatization, and liberalization of foreign direct investment inflows. John Williamson, “What Washington Means by Policy Reform,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, November 1, 2002, https://www.piie.com/commentary /speeches-papers/what-washington-means-policy-reform.

8. Keynes once wrote, “If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people on a level with dentists, that would be splendid.” John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Persuasion (New York: Norton, 1931).

9. J. William Fulbright, The Arrogance of Power (New York: Random House, 1966).