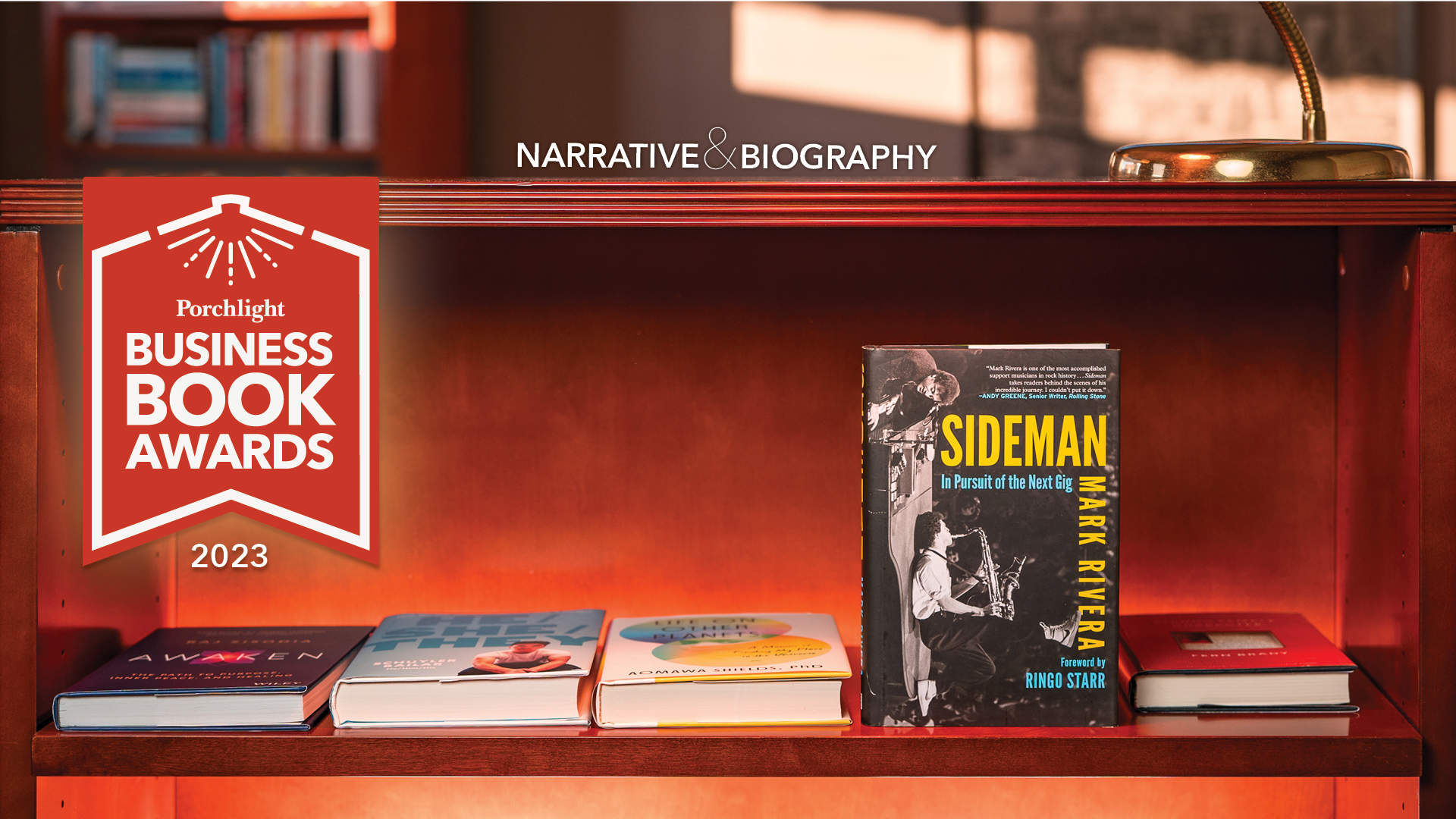

Sideman | An Excerpt from the Narrative & Biography Category

Over Brooklyn, Saturday morning, circa 1965

Beneath, spread out as far as the eye can see, are the apartments and houses of thousands of multigenerational families, each waking to a new day in their quest to make it in a New World. Out of some of these homes, scattered around, middle-school-aged children begin to appear, like ants out of a great mound’s many tunnels. Clutched in their hands are instruments of some kind—a horn, a drum, a violin. Music has been speaking to them and, rain or shine, they answer the call.

…

I was one of those kids. My father would load me and my saxophone into the car and drive the twenty minutes to Empire Boulevard and New York Avenue for Brooklyn Borough-Wide Band practice. It was offered to a select group of middle school musicians who showed talent and dedication to their instrument. And every Saturday, for two hours, my father would sit in the rehearsal hall, a content smile on his face, and listen to a stage full of thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds make noise. He would never miss it.

My father worked as a teletype operator for RCA Communications. He typed amazingly well. I don’t know how he learned to type like that. It was before fax machines and before RCA became automated. What he would type went into pneumatic tubes that shot the communiqué this way and that for overseas transmission. Years later, when they finally automated, he ran RCA’s computers.

He worked three different shifts. There was four to midnight: he’d get home around 12:30, sleep through the night, wake up, and spend the afternoons with us. Then there was 6 am to 2 pm, his favorite shift because he’d leave the house at 5:30 am, go to work at 6, and come home by 2:30. So, even if I was at school, I’d be coming home in time for us to have the whole day together. And then there was midnight to 8 am, the graveyard shift. He’d get home about 8:30 am, sleep a few hours, and start the day again. No matter what the shift, he never complained. Sometimes the guy worked double shifts, and I never knew anybody happier to do it for his family than my father.

And he provided. We didn’t have a lot, but we never thought we didn’t have enough. I remember my parents used to get me these jeans—I was skinny as a rail, they’d get me like a size 22 or 24 waist, and they’d get the length like really, really long. So, being a kid, I’d skin my knees, and my mother would put a patch on the knee, and six months later, the patch would be up by my thigh. I hadn’t outgrown the waist, but I was taller, and you’d see all of these patches crawling up my thigh instead of over the knee I’d scraped.

My father’s childhood hadn’t been fortunate. He came to the Harlem projects straight from Puerto Rico when he was twelve. He spoke no English and was told by his father he needed to get a job to help support the family. Somehow, he’d made it all work—he learned the language, excelled in the local public schools, and put food on the table. He didn’t talk about it much, and it wasn’t until I was older that I really understood the perseverance of this man, but you just got the sense that Dad was always a happy camper. A contented soul whose glass was always halfway full. And that gratitude was infectious. I can remember as a kid coming into the house and seeing my parents dancing or holding hands. They were very much in love, and Mom, who would stutter whenever she got nervous, always looked so relaxed and content when my father was nearby. She, like the rest of us, loved to be around him.

There’s an expression he had—come sin vergüenza, which means “eat without shame.” In other words, if you’re eating a peach, take the bite and let the juice run down your chin—don’t let your pleasure embarrass you. My father believed a person should always live like that: dance like no one is looking, sing like no one is listening. Just enjoy it and be totally absorbed in the moment.

And my father adored music. Jazz. Classical. Latin. We had this great stereo system (like my saxophone, it fell off the truck and Uncle Vinny was there to scoop it up), and my father would record his favorite weekly program on WRVR, Riverside Radio. It was jazz with a DJ named Ed Beach who would do an hour-long set of a particular artist—A Night with Charlie Parker, A Night with Lester Young, A Night with Dizzy Gillespie, A Night with Coleman Hawkins—and my father would run the tape very slowly so it would last for the whole program. Then during the week, he’d sit down and listen to the music, and you could see him get totally absorbed in the sound.

It wasn’t just jazz programs; it was the Latin music, too, and my father would dance around the living room and be unabashedly swept away by the music. Or a piece of classical music would come on and he would close his eyes, rock his head, and the music would take him away. And if it happened to be a piece of music he could sing along to, he’d sing like it didn’t matter what anybody else thought. I remember being a little boy and looking at him, seeing his joy, and it would make me happy without my even knowing why. He was willing to share these moments with me, show me that it was okay to be overcome with something beautiful and take it all in.

So, when I would go to my room and take the saxophone out of my hope chest and play it in the entryway to our building, where the acoustics of the stairwell and hall would allow the sound to reverberate and swell and bounce around me, I too would permit myself to be overcome, to let the joy wash over me. My father was not a musician, but he, more than anyone, showed me that the best way to play music was to celebrate music.

Excerpted from Sideman: In Pursuit of the Next Gig copyright © 2023 by Mark Rivera. Reprinted with permission from Matt Holt Books, an imprint of BenBella Books, Inc. All rights reserved.