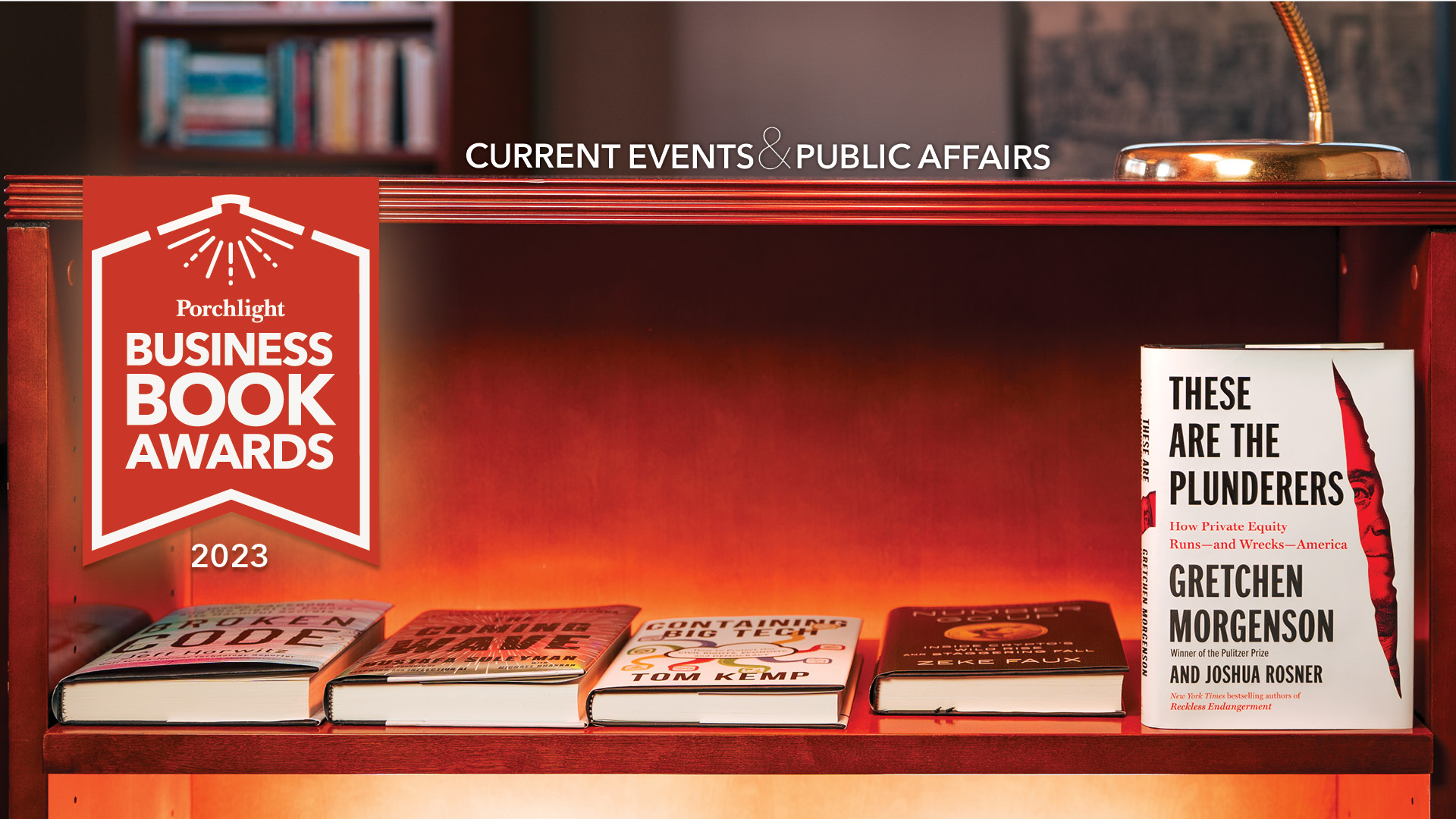

These Are the Plunderers | An Excerpt from the Current Events & Public Affairs Category

In late September 1987, John Dingell, the Michigan Democrat and chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, got the important report he’d requested. A troubling takeover boom was transforming corporate America and imperiling workers, and Dingell had asked the Congressional Research Service, the nonpartisan think tank housed in the Library of Congress, for an analysis of various merger and acquisition deals in the works.

Corporate buyouts were enriching investors as Oliver Stone’s movie Wall Street riveted the nation with Gordon Gekko declaring that “greed, for lack of a better word, is good.” Outside of Hollywood, deep policy questions dogged the transactions: Did buyouts increase company efficiencies and productivity by eliminating “redundancies,” as their proponents claimed, or were the critics right when they said takeovers were job- destroyers that rewarded executives for short- term operational fixes rather than long-term investment and overall prosperity?

“Leveraged Buyouts and the Pot of Gold,” the Congressional Research Service’s report was called, and it aimed to help Congress understand and maybe even restrict the growing takeover binge fueled by a new and risky kind of debt known as junk bonds. These bonds were issued by financially weaker companies that, in earlier days, would not have been able to raise money from investors. But now, thanks in part to these bonds, the nation’s big corporations were undergoing a period of “wrenching adjustment,” the study noted, following years of recession, inflation, and increased competition from companies overseas. “Suddenly businesses were up for grabs,” the congressional researchers concluded, pursued by financiers whose funding came from bond investors willing to take a chance they’d lose money on the securities if it meant receiving a higher interest rate.

Were these deals good or bad for society? The report’s authors dithered. On one hand, the success of the takeovers was “largely anecdotal,” and on the other, the “economic dislocations were difficult to quantify.” It was “open for debate” whether the plant closings and job losses that typically followed these transactions would have occurred regardless, the report said.

[…]

Washington tends to identify burgeoning risks but rarely acts until these threats become full- blown crises. Not surprisingly the hearings resulted in no new laws, after which legislators moved on to other issues. Buyout dealmakers had lobbied heavily against any new restrictions, the New York Times reported, and some in Congress worried that if they acted against leveraged buyouts, they’d cause a market crash. No one wanted a repeat of October 19, 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average had fallen 508 points in a single day. At more than 22 percent, that was the biggest one-session drop in the index’s history, and it still weighed on lawmakers’ minds.

Some in the government played down the impact of leveraged buyouts, predicting that “the market” would correct any excesses. This so-called free-market ideology promoted by Ronald Reagan’s economic team had become the basis of a hands- off culture in Washington. Nicholas Brady, the treasury secretary under George H. W. Bush, espoused this idea, telling Congress in 1989 that he expected the troubling takeover deals would soon become “a thing of the past.” Brady could not have been more wrong. In fact, the transactions were to become a very big thing of the future. And “Pot of Gold” didn’t begin to describe the riches an elite gang of financiers would reap from them.

More than thirty years later, the effects of what began as the leveraged buyout boom in the late eighties, paired with the belief that markets and deregulation support society, are devastatingly clear. Today, there is little room for equivocation. The economic wreckage caused by the takeover titans is real and measurable. Except now they call their industry private equity—a name that conveys suave sophistication but none of its brutality. The riches amassed by the people overseeing these money- spinning machines—and most of them are white males—are simply staggering.

Armed with decades of data, we now have unsettling studies and proof of the perverse impacts these buyouts have on workers, customers, pensioners— everyone but the dealmakers. Residents of nursing homes owned by private equity firms, among the nation’s most vulnerable populations, have been especially hurt: one study showed residents experienced 10 percent more deaths in facilities owned by private equity firms than in other entities, due to decreased staff, reduced compliance with standards of care, and more. Another study tied private equity ownership of nursing homes to increases in emergency room visits and hospitalizations, and higher Medicare costs.

Beyond healthcare, a major and devastating focus of the financiers, private equity buyouts across industries result in ten times as many bankruptcy filings, research shows. Waves of job losses result, wrecking families and lives and slashing tax receipts. The high costs associated with these investments deplete pensioners’ benefits and add to government deficits. Even the planet bears a brunt: in recent years, as public companies have come under pressure to jettison businesses that strip- mine ecosystems or pollute the planet, private equity has rushed in to buy them, keeping alive fouling operations that might otherwise be mothballed.

Assessing the damage that this rapacious form of capitalism has wrought on our country and our citizens is overdue. In this book, we examine the how, the why, and, most significantly, the whom in this calamity in order to educate, inform, and maybe even end the carnage.

Those on the losing end in our economy are easy to recognize—the working poor, rank-and-file corporate employees, pensioners and savers, small businesses and the middle class. Identifying the winners and how they’ve ravaged our economy and exploited Main Street America is what this book is about.

Stanley Sporkin was an aggressive prosecutor, federal district judge, CIA general counsel, conservative, and the first director of enforcement for the Securities and Exchange Commission in the 1970s. He summed it up this way: “Capitalism is the greatest thing going,” he said, “but unchecked, it’s its own undoing.”

Excerpted from These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—And Wrecks—America with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © by Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner. All rights reserved.