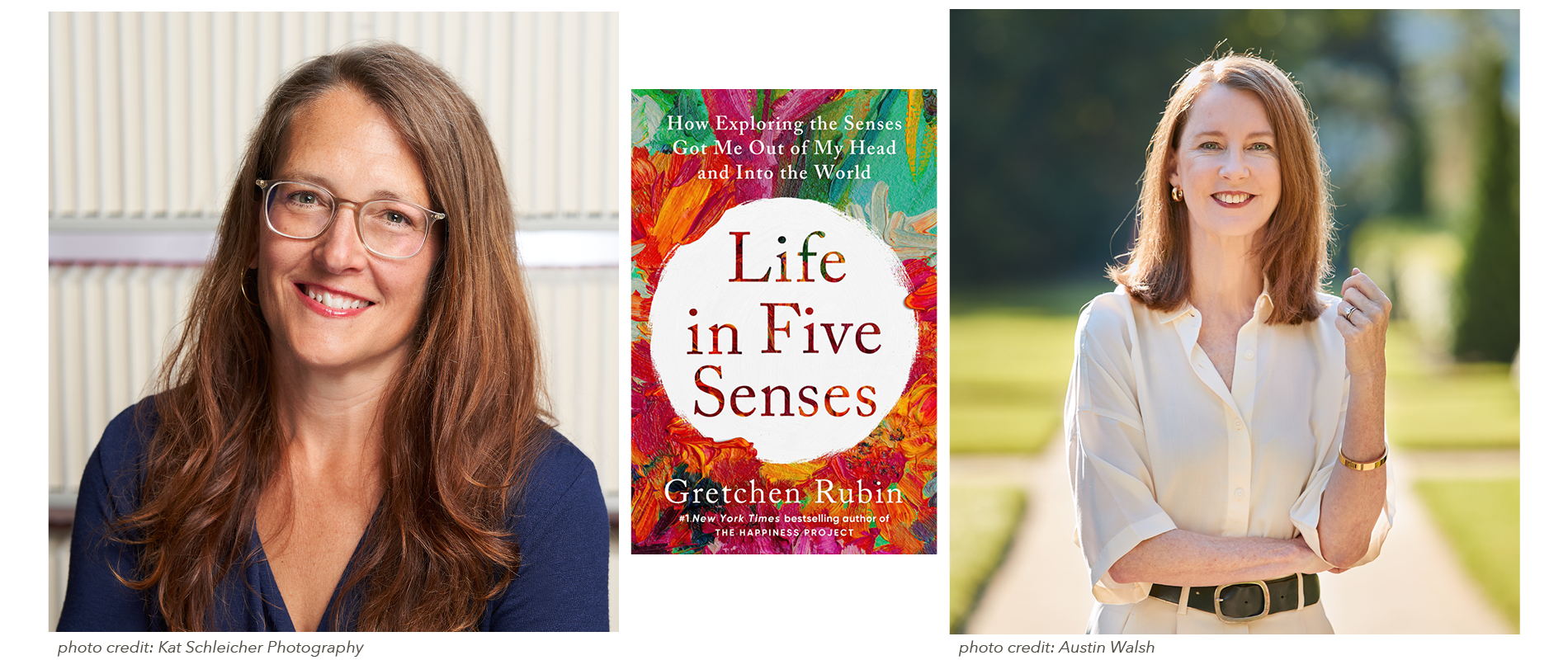

A Q&A with Gretchen Rubin

Major life events, especially unexpected medical emergencies, often cause us to bring what’s most important in our lives into sharper focus. For Gretchen Rubin, it was a common case of conjunctivitis and a casual remark from her eye doctor that she should promptly schedule a follow up visit, as her extreme nearsightedness puts her at a higher risk of a detached retina. This was something she had never been told before, and the news hit her in a way that was life changing. Relating the experience of her walk home that day, she writes:

In that time, I woke to a profound truth: I had my one body and its capacities right now, and I wouldn’t have them forever.

The suggestion from her doctor that she could lose some of her sight caused her to pay closer attention to everything she saw on that walk home, to really relish her ability to take it all in. It heightened her senses and the intensity of the world around her. Determined to experience that sense of sharp focus and the resulting ability to stay in the present moment more readily, she embarked on a journey that would lead to her new book, Life in Five Senses. A product of both deep research and a personal challenge to experience her own senses more consciously, it is a book that will help us develop a deeper connection to our own bodies and more deliberately interact with all the gifts the world around us has on offer.

I recently came up with five questions for Rubin about Life in Five Senses, which she was kind enough to answer. Our conversation is below.

Sally Haldorson: I love that, in your desire to tap into the power of your senses, you first head to the library. That, to reconnect to your senses, you felt you first needed a plan. You mention your tendency “to turn personal challenges into professional projects.” This might seem like a form of rigidity to many, but it sounds like this practice is liberating for you. Can you explain how turning it into an intellectual exercise actually helped you get out of your head and in touch with your senses?

Gretchen Rubin: You’re right! In my work, I’m a kind of a street scientist who uses the world as my laboratory and myself as a guinea pig.

As I began to plan my investigations to go deeper into the senses, I knew that I couldn’t magically outgrow myself; if I wanted to change, I must make a change.

Over time, I’ve learned, I gain more from taking specific action than from making lofty but vague resolutions. I wouldn’t be able to prod myself to “Be present in the moment,” but I could “Take a deep sniff of saffron” and with its earthy-sweet scent, appreciate that moment.

Because I love habits, routine, and familiarity, I took a methodical approach. For each sense, I started with research, and then, to engage more fully with each sense, I devised a mix of playful, practical exercises: took classes (the more we know, the more we notice), planned adventures, or tried simple experiments.

Also—and this was particularly ambitious—I decided to visit the Metropolitan Museum every day for a year. This exercise appealed to me because I’ve always been powerfully attracted to routine and repetition, and I take great pleasure in the expected. With a daily visit, I could explore what I saw, heard, smelled, tasted, and touched over time, as well as discover what insights I’d gain through familiarity.

My study of the five senses wasn’t exhaustive; of course; I studied my five senses. Each of us comes from our own time and place; each of us experiences the world with our own particular complement of senses, whatever those might be. I knew, too, that I could live a rich, meaningful life even if I lost some of my senses. My fear was that one day I’d regret all I’d ignored.

From my small study of my own senses, I discovered larger truths about how we can tap into our senses to be happier, healthier, more productive, and more creative.

Sally Haldorson: Like so much in our modern world, everything we allow in (or are forced to allow in) with our senses is too much, a sort of escalated or optimized version. Our take-out foods spoil us with salt levels, our ear buds channel sound directly into our ears, signs in Time Square with millions of LEDs stretching thousands of square feet make us stand back in awe barely able to process what we see. And it seems we may have become sort of immune or even passive in using our senses. What is so refreshing about your book is that you make using our senses a proactive pursuit. How does searching out sensory experiences differ from those that are produced for us, that we have little choice in experiencing?

Gretchen Rubin: For all the talk about the metaverse, people are more interested in the universe! We crave to make direct contact with the world. That’s why so many experiences bill themselves as “immersive.”

When we take action to shape our sensory environments, we can help ourselves to feel calmer, more focused, more energetic, and more creative. We can find new ways to connect with other people—and ourselves.

Sally Haldorson: What’s a taste party, and what can we learn (beyond finding new favorite foods) from challenging our palates?

Gretchen Rubin: In general, people love taste-related activities such as cooking, visiting farmers’ markets, sharing meals with friends, and trying new recipes.

For me, however, taste was a neglected sense. (Curious to know your own “neglected sense?” You can take my fun, free quiz, “What’s Your Neglected Sense?”) I ate the same foods all the time, and I rarely paid much attention to what I put in my mouth. I wanted to tap into the power of taste—especially its power to bring people together.

When I’d gone to a two-day course at Flavor University, the taste comparisons were my favorite exercise. I decided to do the same thing with my friends.

I decided to throw a “Taste Party” where my friends and I could compare and review different tastes.

Before my guests arrived, I set out samples of apples, potato chips, nuts, and chocolate bars for us to judge according to criteria such as texture, aftertaste, and aroma. I poured out a small cup of a mystery drink (spoiler alert: it was Red Bull). I gave each person a dollop of ketchup, so together we could appreciate the magic of Heinz Ketchup: it’s the rare item that features all five of the basic tastes of sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami.

This Taste Party was tremendously fun. My friends and I weren’t just socialising; we were sharing a sensory experience, and our conversation felt unusually warm and intimate. Learning little details—one friend was sensitive to food texture, another dislikes most fruits—somehow gave me a better sense of their natures.

Sally Haldorson: In your chapter about hearing, you tell a story about going to The Met and really experiencing your time there in order to “lower stress and deal with anxiety.” And it echoes the 5-Senses Grounding strategy that is often recommended for people experiencing anxiety or panic attacks–notice 5 things you can see, 4 things you can hear, 3 things you can touch, 2 things you can smell, 1 thing you can taste. But as you mention in this chapter, really hearing things can also put us under stress, and you actually became “more aware of unpleasant noise.” How can we start “listening” better?

Gretchen Rubin: Listening may seem undemanding, but it’s an active, taxing activity. And of all the things we listen to, listening to people is among the most important. To help me do a better job, I wrote a “Manifesto for Listening”:

- Show my attention: turn my body and eyes to face the other person, put down my book or phone, nod, make eye contact, say “mmm-hmm,” take notes.

- Don’t rush to fill a silence.

- Ask clarifying questions; paraphrase or summarize to show that I understand—or not.

- Respect what other people want to talk about: if they raise a subject, discuss it; if they steer away from a subject, don’t bring it up again unless necessary.

- Don’t jump in with judgment or suggestions. (I often urge people to read a particular book.)

- Stow my phone. (One study found that the mere presence of a phone made people sitting around a table feel more detached and less inclined to start a meaningful conversation.[i])

- Listen for what’s not being said.

- Don’t avoid painful subjects. (I often do this, before I’m even consciously aware of what’s happening.)

- Let people talk themselves into their solution, rather than supply my solution.

- When in doubt, stop talking.

Sally Haldorson: One of the givens of life, beyond death and taxes, is that those of us who are lucky enough to live long lives will inevitably lose the sharpness of our senses, if not lose one or more of them completely. You write: “[M]y new awareness of my own unique sensory world reminded me that I may not have it forever. So often, we value what we have only once we’ve lost it or fear we might lose it.” And in so many ways, your book is a reminder that we should revel in the present. The last section, “Try This at Home,” guides us on how to begin. What are the first steps someone might take to remind themselves to linger over their sensory experiences?

One simple exercise that I found immensely valuable was to keep a Five-Senses Journal.

I pulled a lined notebook from a shelf and wrote “See,” “Hear,” “Smell, “Taste,” and “Touch” down the page. At the end of every day, I would note my most memorable sensations.

My first day’s entries of sense-highlights included:

See: gorgeous silvery black fur of a Weimaraner dog, looked frosted

Hear: walking downtown, heard church bells chime the hour

Smell: Barnaby needs a bath

Taste: surprising, delicious smoky flavor in a salad

Touch: scratchy sisal rug at my in-laws’ apartment

My Five-Senses Journal proved to be invaluable as a quick daily reminder to maintain my focus on my five senses forever—and it also felt like a gratitude journal. How many moments passed through me, intense, endless, but unremembered? I must pay attention, I must appreciate. Keeping this journal helped me to use my full attention. It gave me the sense of vitality that I craved.