A Q&A with Jayme Ringleb

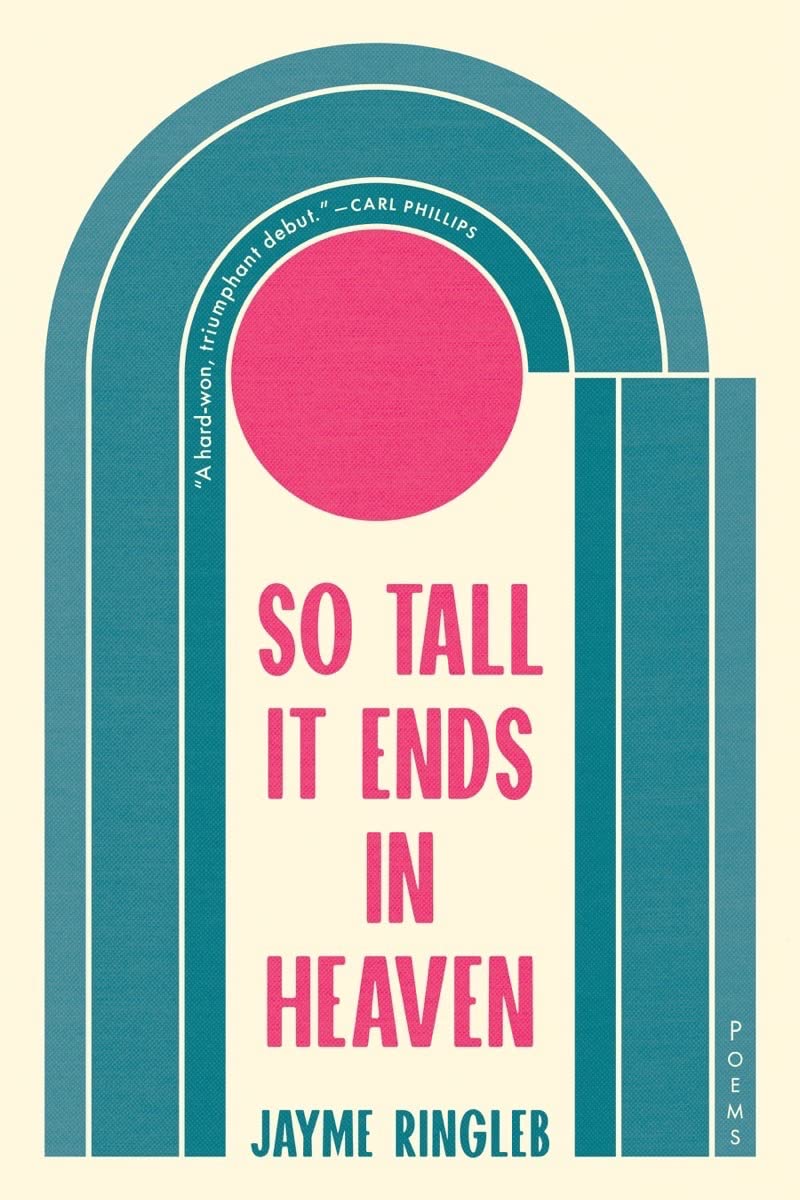

Jayme Ringleb writes their heart out onto each page of this debut collection. A poignant and heart wrenching journey through grief, estrangement, and sexuality, So Tall It Ends in Heaven is a wonderous read of poems that have such depth that I found myself sitting back to allow each one to seep in during the stillness of the moment.

...

Porchlight Book Company: The art of creating poetry is a raw undertaking. Do you have a writing ritual or technique you do before sitting down?

Jayme Ringleb: I don’t have a particular ritual, no, but I do tend to let whatever idea I have for a poem percolate for a good while before actually putting pencil to paper. Sometimes, there are parts of that prewriting process that I think you could argue are ritualized: long walks, bike rides, road trips, or even pacing around the house or in a closed room. For me, a sense of movement seems to help the ideas come in a more unedited way.

Porchlight Book Company: Writing about the end of marriage and coming to terms with being on your own once more, you explore the meaning of love, the grief it brings, and the continuation of the self after grief. I found your collection to be raw and elegant—as well as being very open to change. You write of travelling through Europe to find an estranged father and, though you follow him and people with his likeness, you never go up to him to recultivate that relationship. Are these relationships, as different as they are, but both intimate in different ways and both broken, connected in some way?

Jayme Ringleb: It's important for me to keep a good bit of distance between myself and my speaker. Sometimes that distance is absurdly small, and it’s certainly the case that there are many details of my life that enter the poems—but the speaker is ultimately distinct from me, and I’ve tweaked his narrative in some ways to distinguish it from mine. I have not been married, for example, though the figure of the husband in the book is a kind of composite of many people with whom I’ve shared failed relationships. For my speaker, though, that failed marriage (which I don’t believe he ended, for what it’s worth) did initiate a particular need to belong, to give his devotion to someone or something. And this eventually leads him to search for his father, yes.

Porchlight Book Company: You speak of grief in many of its forms. The grief of losing love, the grief of not being accepted for who you are by a parent, but also the small griefs that hang in the air as we move throughout our days. Was this collection a way to grapple with the griefs you experienced within this time?

Jayme Ringleb: I do assume that poetry has offered me a way to reimagine my emotions and engage with consolation. The act of transforming a psychological pressure (grief, for example, or rage) into a tangible piece of writing has, I think, been a healthy practice for me, a way of redirecting what might otherwise become unhealthy and festering emotions. I think it’s also about controlling narrative. If I can tell or retell a story, I can control the outcome of that story: I can make the story end in healing. This emotional relationship that I’ve built around poetry is something that the collection inevitably communicates, I think, even if the collection’s speaker and I aren’t the same.

Porchlight Book Company: Like you, I grew up in a religious family, and it seems that the stories and symbolism can trickle down as we grow into ourselves. Throughout this collection you mention God or the idea of God several times. How has your idea of God evolved and what place does faith have in your life, or in your work, today?

Jayme Ringleb: I’d like to again acknowledge the distance between myself and my speaker here. Faith in gods or religious and spiritual texts is not a part of who I am, and it has not been a part of who I am for a very long time. But those narratives of faith and devotion have certainly informed the way that my speaker navigates communicating himself and his love for others. It is a way of understanding the world, and he feels ambivalently about that, largely because he feels both trapped and rejected by the religious perspectives he has inherited.

Porchlight Book Company: The poem North Florida, is such a beautiful look at an everyday moment. I feel like I am peering into your window as you go through your morning routine. What are your thoughts when writing a piece like this? How simple (or complicated) is it to write a poem about such seemingly simple moments, and how do you elevate them in the way you do in North Florida?

Jayme Ringleb: My feeling about the quotidian in writing is that, if the speaker’s psychological presence and conflict is sharpened enough, daily or mundane details are suddenly very energetic and dynamic. They can take on the same type of complexity and attention of more dramatic, high-stake narrative events. In this way, they’re not simpler or more complicated than many other themes in my writing—the process is very similar, even when the themes shift.

Porchlight Book Company: Love Poem to the Son My Father Wished For contains a beautiful, heart-wrenching rawness of reaching out to the person who you think your father wanted you to be. You speak of your true self and try to envision this person. It also seems a bit like a eulogy. Is this purposeful? Is there any overlap or connection between you and that imagined person?

Jayme Ringleb: It’s a kind of double imagining: the speaker, who I have imagined, is imagining and expressing love for the man who his father would want him to be. It’s not intended to resemble a eulogy, though it may be somewhat elegiac. And there is overlap between the speaker and the man he imagines, yes: they are the same, except that the speaker’s life has taken a different course because he is neither closeted nor faithful to the religion of his upbringing.

Porchlight Book Company: Throughout the collection you speak of love for one’s father and the longing to feel accepted by him—even after he refuses to accept your sexuality and the relationship and so much of the love is lost. Can you speak more to your perspective on what it would take to maintain a relationship with someone who doesn’t accept you? Is it worth it to try?

Jayme Ringleb: The losses you describe are my speaker’s, and I’d like to draw a boundary around my own. Seeking to rebuild a relationship with a father who has rejected him is what this speaker decides to do—but he suffers because of that pursuit, and his eventual goal shifts to favor self-love over winning the love or approval of others. I need to be clear here, though: what my speaker does is not what I believe anyone else must do. What it would take and whether it is “worth it” for someone to maintain a relationship with a family member who doesn’t accept who they are—that question is an immensely personal one, and the possible answers to it depend entirely on the identities and relationships about which the question is being asked.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jayme Ringleb is a queer writer raised in the southern United States and northern Italy. Jayme's poems have appeared recently in Poetry, Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, and Ploughshares. An assistant professor of English at Meredith College, Jayme lives in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Jayme Ringleb is a queer writer raised in the southern United States and northern Italy. Jayme's poems have appeared recently in Poetry, Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, and Ploughshares. An assistant professor of English at Meredith College, Jayme lives in Raleigh, North Carolina.

ABOUT THE BOOK

With lush and deeply intimate language, Jayme Ringleb’s debut collection So Tall It Ends in Heaven explores sexuality, estrangement, and the distances we travel for love.

Following the end of a marriage, So Tall It Ends in Heaven’s queer southern speaker tries to restore a relationship with his father. His father lives across an ocean, but more keeps them apart than just that: the father rejected his son long ago after learning that his son is gay. The poems search for answers across the United States and Europe, in and out of historical imagination, as the speaker struggles to separate his understanding of devotion and belonging from the constant losses in his life. Drawing from—and subverting—the formal traditions of love poems, parables, and elegies, the collection claims a vital space for one’s own solace. “Nobody will love you / like this poem does,” the speaker says; “Tell this poem / what you want. // Anything.”