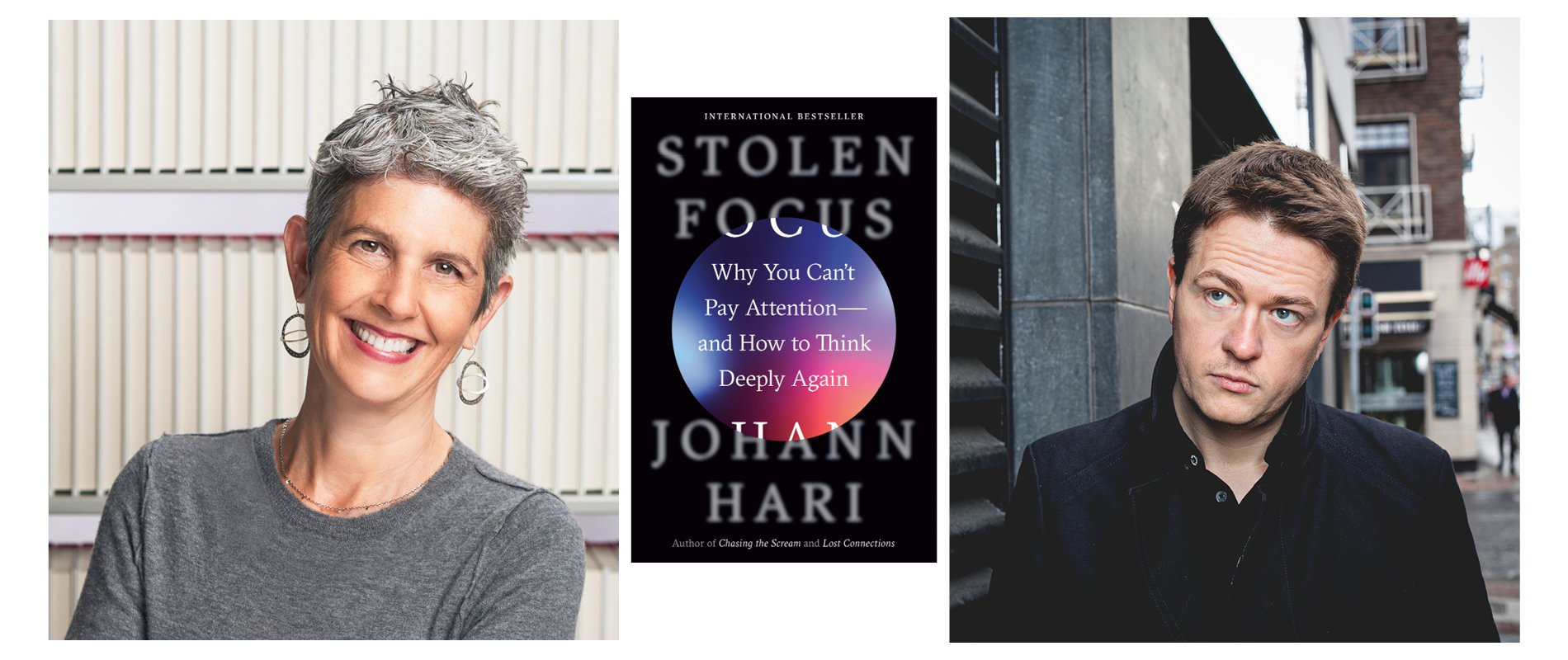

A Q&A with Johann Hari,

Author of Stolen Focus

Of the many compelling aspects of Stolen Focus, the 2022 Porchlight Business Book of the Year, the personal context in which Johann Hari situates his investigation and his alarm is revealing and relatable. You’ll find some of that evident, below, in his answers to questions I sent him recently. And even as he discloses how he came to the problem personally, Hari develops a hopeful, fearless case for how we must—and can—combat the loss of human attention. He makes clear that in doing so, we can renew our imaginations and inspire our collective energies to fight for the common good. Stolen Focus is, in many ways, the book we need right now.

Rebecca Schwartz: Johann, clearly Stolen Focus made quite an impression on many of us here at Porchlight so I’m delighted that you’ve agreed to this written conversation. For people who have not yet read your new book, however, I’d like it if you would introduce it a bit. Perhaps tell us why you wanted to write it, the way you went about studying and researching for it, and broadly what you discovered?

Johann Hari: I am totally thrilled by your recognition of the book. Thank you!

I wrote the book for a personal reason: I could feel my own ability to focus and pay attention was getting worse. Things that are so important to me—like reading books—were getting harder and harder. This is happening to lots of us. The average office worker now focuses on any one task for only three minutes. For every one child identified with serious attention problems when I was 7, there’s now 100 children in that position.

But I was afraid to look into this problem. I thought maybe I was just weak, and lacking will power. Then something happened.

When he was fifteen, my godson Adam (not his real name—I have changed it to protect his privacy) dropped out of school and spent literally almost all his waking hours at home alternating blankly between screens—his phone, an infinite scroll of Whatsapp and Facebook messages, and his iPad, on which he watched a blur of YouTube and porn. He struggled to stay with a topic of conversation for more than a few minutes without jerking back to a screen or jerkily switching to another topic. He seemed to be whirring at the speed of Snapchat, somewhere where nothing still or serious could reach him. He was intelligent, decent, kind—but it was like nothing could gain any traction in his mind.

I couldn’t bear to see this happen to him—and I couldn’t bear to feel my own ability to pay attention fracturing. In decided to do something drastic. When he was a little boy, he had been obsessed with Elvis. I said to him—let’s go to Graceland. We’ll travel all over the South. But there’s one condition. You have to use your phone only once, at the end of the day. He agreed.

When you arrive at the gates of Graceland, there is no longer a human being whose job is to show you around. You are handed an iPad, and you put in little earbuds, and the iPad tells you what to do—turn left; turn right; walk forward. In each room, the iPad, in the voice of some forgotten actor, tells you about the room you are in, and a photograph of it appears on the screen. So we walked around Graceland alone, staring at the iPad. We were surrounded by Canadians and Koreans and a whole United Nations of blank-faced people, looking down, seeing nothing around them. Nobody was looking for long at anything but their screens. I watched them as we walked, feeling more and more tense. Occasionally, somebody would look away from the iPad and I felt a flicker of hope, and I would try to make eye contact with them, to shrug, to say, hey, we’re the only ones looking around, we’re the ones who travelled thousands of miles and decided to actually see the things in front of us—but every time this happened, I realised they had broken contact with the iPad only to take out their phones and snap a selfie.

When we got to the Jungle Room—Elvis’ favourite place in the mansion—the iPad was chattering away when in front of me, a middle-aged man turned to his wife. In front of us, I could see the large fake pot-plants that Elvis had bought, to turn this room into his own artificial jungle. The fake plants were still there, sagging sadly. “Honey,” he said, “this is amazing. Look.” He waved the iPad in her direction, and then began to move his finger across it. “If you swipe left, you can see the Jungle Room to the left. And if you swipe right, you can see the Jungle Room to the right.” His wife stared, smiled, and began to swipe at her own iPad.

I watched them. They swiped back and forth, looking at the different dimensions of the room. I leaned forward. “But, sir,” I said, “there’s an old-fashioned form of swiping you can do. It’s called turning your head. Because we’re here. We’re in the Jungle Room. You don’t have to see it on your screen. You can see it unmediated. Here. Look.” I waved my hand at it, and the fake green leaves rustled a little.

The man and his wife backed away from me a few inches. “Look!” I said, in a louder voice than I intended. “Don’t you see? We’re there. We’re actually there. There’s no need for your screen. We are in the jungle room.” They hurried out of the room, glancing back at me with a who’s-that-loon shake of the head, and I could feel my heart beating fast. I turned to Adam, ready to laugh, to share the irony with him, to release my anger—but he was in a corner, holding his phone under his jacket, flicking through Snapchat.

At every stage in this trip, he had broken his promise. When the plane first touched down in New Orleans two weeks before, he immediately took out his phone, while we were still in our seats. “You promised not to use it,” I said. He replied: “I meant I wouldn’t make phone calls. I can’t not use Snapchat and texting, obviously.” He said this with baffled sincerity, as if I had asked him to hold his breath for ten days. I watched him scrolling through his phone in the Jungle Room silently. Milling past him was a stream of people also staring at their screens. I felt as alone as if I had been standing in an empty Iowa cornfield miles from another human. I strode up to Adam and snatched his phone from his grasp. “We can’t live like this!” I said. “You don’t know how to be present! You are missing your life! You’re afraid of missing out—that’s why you are checking your screen all the time? By doing that, you are guaranteeing you are missing out! You are missing your one and only life! You can’t see the things that are right in front of you, the things you have been longing to see since you were a little boy! None of these people can! Look at them!”

I was talking loudly, but in their i-phone i-solation, most people around us didn’t even notice. Adam snatched his phone back from me, told me (not without some justification) that I was acting like a freak, and stomped away, out past Elvis’s grave, and into the Memphis morning.

I spent hours walking listlessly between Elvis’s various Rolls Royces, which are displayed in the adjoining museum, and finally I found Adam again as night fell in the Heartbreak Hotel across the street, where we were staying. He was sitting next to the swimming pool, which was shaped like a giant guitar, and as Elvis sang in a 24/7 loop over this scene, he looked sad. I realised as I sat with him that, like all the most volcanic anger, my rage towards him—which had been spitting out throughout this trip—was really anger towards myself. His inability to focus, his constant distraction, the inability of the people at Graceland to see the place to which they had travelled, was something I felt rising within myself. I was fracturing like they were fracturing. I was losing my ability to be present too. And I hated it.

“I know something’s wrong,” Adam said to me softly, holding his phone tightly in his hand. “But I have no idea how to fix it.” Then he went back to texting. I took Adam away to escape our inability to focus—and what I found is that there was no escape, because this problem was everywhere.

That’s when I knew I had to go on a journey to understand from the leading scientists in the world why this is happening to so many of us—and, crucially, how we can solve it.

I travelled all over the world—from Moscow to Miami to Melbourne—to interview over 200 of the leading experts on attention and focus and to do a deep dive into their research. I wanted to find out: why is this happening, and what can we do about it? I discovered the reasons are more complex than we think. There are twelve forces that the science shows are wrecking our ability to focus and to think deeply. They range very widely—from the way our offices work, to the food we eat, to the way our kids’ schools work. Once we understand the science of why this is happening to all of us, we can actually deal with it.

To explain why this is so important, I would say: Think about anything you’ve ever achieved that you’re proud of—whether it’s starting a business, or being a good parent, or learning to play the guitar. Whatever that thing is, it required a huge amount of sustained focus and attention. If your ability to focus breaks down, your ability to solve your problems breaks down. Your ability to achieve your goals breaks down. When your attention collapses, you feel worse about yourself—because you actually are less competent. So a crisis of attention produces a crisis of greater anxiety and depression.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can come together and fix these problems. These changes ruining our attention are quite recent in most cases. As Dr. James Williams explained to me, the axe existed for 1.4 million years before anyone thought to put a handle on it. The entire internet has existed for only 10,000 days. We can fix this stuff if we want to.

Rebecca Schwartz: Let’s start specifically with children, because in some ways they’re clearly most vulnerable to having their attention manipulated. As a veteran—for better and worse—of what was called in America in the 1960s and '70s the “free school” movement, I was really taken by your discussions of the Sudbury Valley School in Massachusetts and the Let Grow movement. What did your investigation into schooling reveal to you about the way we in America, England, and other “advanced” countries typically approach educating our kids and its effect on attention—and what could we do differently and better?

Johann Hari: Attention evolved to attach to meaning. If I gave you now a book about a subject you really care about, you’d find it far easier to focus on than if I gave you a book about a subject you don’t find interesting. Everyone knows that.

The more kids are connected to the meaning of what they study, the easier they find it to pay attention. But we have—over the past three decades—stripped meaning out of schooling. We have rebuilt our education systems around getting kids to memorise meaningless crap, for tests that reveal nothing. It’s one of the reasons our kids are struggling so much to focus at school. As you say, I went to schools that are all about kids discovering meaning—and they have vastly better attention there.

Rebecca Schwartz: Related to the question about how we educate our kids, this one has a bit of a windy introduction: when I was nine and living with my parents in a small commune in Maine, the children living with us and I complained to the adults about being bored. I recall clearly how profoundly uninterested they were in our boredom; they told us to figure it out ourselves. So… we wrote a play. It took days of concentration and back and forth and squabbling and creating—and then we recruited other kids and we performed it. And like some of the kids you talk about, we felt proud and good! As you discuss, the loss of this opportunity, the loss of mind-wandering and filling-in time with one’s own creativity and even community has had enormous effects on kids’ development. That was a bit of a specific example but it speaks to what you discuss in the book. You note that mind-wandering is viewed as “anti-productive,” when it’s actually the opposite, right? Could you talk a bit about what you came to understand from your own experience and your research about mind-wandering or daydreaming?

Johann Hari: I used to think mind-wandering was a waste of time—but then I interviewed the leading experts on mind-wandering, and studied their evidence. They have shown that when you let your mind wander—say, you go for a walk, without anything to listen to, or a phone to interrupt you—your mind actually starts to do lots of important things. It processes what has happened in the past and makes sense of it. It anticipates the future, and prepares you for it. And it starts to create connections between things that you had not previously connected—which is where creativity comes from. So mind-wondering is essential.

Rebecca Schwartz: Connected to mind-wandering, you devote a chapter to what you call the “crippling of our flow states.” Talk to us about what flow state is, why it’s important for us to find ourselves in it, and how it’s being “crippled” as you say by technology?

Johann Hari: Almost everyone reading this will have experienced a flow-state at some point. It’s when you are doing something meaningful to you, and you really get into it, and time falls away, and your ego seems to vanish, and you find yourself focusing deeply and effortlessly. One rock-climber said once that when you are in flow, it feels like you are the rock you’re climbing. Flow is the deepest form of attention human beings can offer—it’s a gusher of focus that lies inside all of us, and when we drill in the right way, attention comes easily and can flow for hours. But how do we get there?

I interviewed Professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in Claremont, California, who was the first scientist to study flow-states and researched them for over forty years. From his research, I learned there are three key factors which you need to get into flow. Firstly you need to choose one goal. Flow takes all your mental energy, deployed deliberately in one direction. Secondly, that goal needs to be meaningful to you—you can’t flow into a goal that you don’t care about. Thirdly, it helps if what you are doing is at the edge of your abilities—if, say, the rock you are climbing is slightly higher and harder than the last rock you climbed. If you do these three things, you hugely increase your chances of getting into flow—and activating your strongest powers of attention.

Flow is being crippled because we are being constantly interrupted.

Rebecca Schwartz: Now let’s get into what you devote the bulk of the book to. You cite a neurology professor who uses this great metaphor: he describes our brain as a nightclub, and the bouncer out front as the gatekeeper holding at bay the forces that want to steal our attention. The bouncer (what a neurologist would call a pre-frontal cortex) can hold off several of the club crashers, or unwanted distractions, but not all—perhaps not even most. I have a two part question:

First, why we can’t just will ourselves to focus, to have a super-strong bouncer up front who allows us to pay attention, and what are some of those external forces are that overwhelm us? You discuss many in your book—twelve—so tell us about some of them, please.

And, secondly, given all these forces, and the way many of them are intentionally created to put us in the state we’re in (e.g. infinite scroll, the modern spin on “if it bleeds it leads” using algorithms that privilege outrage and falsehoods over kindness and truth, etc.) what is the role of the individual in the great maw of the machine? What can we do to help ourselves, even as we agitate for broader corporate and structural change?

Johann Hari: I went to interview Professor Earl Miller, one of the leading neuroscientists at M.I.T., and he explained to me a crucial fact about the human brain: “Your brain can only produce one or two thoughts” in your conscious mind at once. That’s it. “We’re very, very single-minded.” We have “very limited cognitive capacity.” But we believe that we can do several things at once—that we can (say) write an article, while being interrupted by texts. But when neuroscientists studied this, they found that when people do this, they are actually—as Earl explained—“juggling. They’re switching back and forth. They don’t notice the switching because their brain sort of papers it over, to give a seamless experience of consciousness, but what they’re actually doing is switching and reconfiguring their brain moment-to-moment, task-to-task—[and] that comes with a cost.” The technical term for it is “the switch-cost effect.” When you try to do more than one thing at a time, you do all the things you are trying to do much less competently. You make more mistakes; you remember less of what you’re doing; you are much less creative. This is a really large effect. Being chronically interrupted is twice as bad for your intelligence, in the short term, as getting stoned.

This is why Professor Miller says we are living “a perfect storm of cognitive degradation, as a result of distraction.”

That switching isn’t happening by accident. It’s happening because of some big social forces. Let’s look at two. In Silicon Valley, I interviewed lots of people who designed key aspects of the world we now live in. They explained to me that to understand why social media, at the moment, is so bad for your attention, you need to grasp one thing. Right now, every minute you spend scrolling through their feeds, these companies make more money—by monitoring you, learning how you think, and selling that information about you to advertisers. Every time you put down your phone, that revenue stream disappears. So their products are designed, deliberately, to maximally capture and hold your attention. The cleverest engineers in the world spend all day figuring out how to get you to switch tasks to their site. Your distraction is their fuel. So they learn what most engages you, and they target it ruthlessly. They train you to crave the rewards their sites offer. The former Google engineer (and my friend) Tristan Harris has become a viral star in the documentary ‘The Social Dilemma’ since I started interviewing him three years ago, and he put the problem plainly when he testified before the Senate: “You can try having self-control, but there are a thousand engineers on the other side of the screen working against you.”

So we need to regulate Big Tech, in practical and targeted ways, to stop them doing this to us.

For all of the twelve factors, we have to tackle them at two levels—defence and offence. There are dozens of things we can do as isolated individuals to protect our attention, and our kids’ attention. I describe them in the book. To give one example: I own something called a K-Safe. It’s a timed plastic safe, that will lock away your phone for anything between five minutes and a whole day. I won’t sit down to watch a film with my partner unless we both oput our phones in the phone jail. I won’t have my friends round for dinner unless we all imprison our phones. The pleasure of really focusing is so much greater than the pleasure of the next shitty notification on your phone.

I am passionately in favour of these changes. They will really help. But I want to be really honest with people—they will only get us so far. We have to also go on the offence against the forces that are doing this to us. This isn’t happening to us because we all individually failed. It is happening because of being changes that none of us chose. That’s why we also have to go on offence.

Rebecca Schwartz: Given what we you establish about the very intentional way Facebook, for example, is designed to highjack our time and attention for their own profit, tell us about the ways in which technology could be designed differently, could be used as a force for good. You use the example of how there was formerly lead in all gasoline—until there wasn’t. Talk about this shift and how it would look in the attention arena, if you would.

Johann Hari: The way I see it is that we’re in a race. To one side, there’s all these 12 factors undermining our attention and focus, from Big Tech to the food industry. If we don’t act, they’ll become more powerful. Paul Garaham, one of the biggest investors in Silicon Valley, says that the world will be more addictive in the next forty years than it was in the last forty. Think about how much more addictive TikTok is to your kids than Facebook. On the other side of that race, there has to be a movement of all of us, saying—no. No you don’t get to do that to my brain. No you don’t get to do that to my children. No, we choose a better life—one with plenty of tech, to be sure; but one where we can think deeply, where we can read books, where our children can play outside. If we want that life, we can get it—I show in the book how. But you don’t get what you don’t fight for. We need to decide if we really value attention—for ourselves, and for our children—and if we do, we need to fight for it.

Rebecca Schwartz: I’d like to talk about what seems like a barrier to entry to the whole notion of solutions to this enormous, deeply problematic reality: People like to watch silly videos or movie star weddings while they’re waiting in line at the grocery checkout; they might even feel like they need to be shown outrage and ugliness to remain current in their own circles. How do we reverse the wiring on this? And to extend that, you make the link between our lack of focus and environmental collapse. How, then, do we get people to want to agitate for the changes you emphasize as so urgently needed—for us personally, collectively, and for our literal climate?

Johann Hari: I like to watch silly videos sometimes too—I just don’t want my whole life to consist of them. We want to have a mixed life—with some speedy, silly stuff, and some depth and contemplation. At the moment, we are way too skewed in one direction. That’s why we need to tackle the 12 factors that are harming our attention.

Rebecca Schwartz: As you demonstrate clearly, there’s a lot of cause for anger and outrage at the ways in which our environments—educational, technological, physical—have put us in the situation in which we now find ourselves. But you make a point of stressing that this is not a time for despair, that there’s reason, in fact, to be optimistic. Can you talk about some of the solutions you discuss (some of which are actually in play) and so why you feel this optimism?

Johann Hari: As human beings, we have solved bigger problems than this before. We need to shift our psychology on this question. This isn’t a fault in me, or you, or your kids. There’s something wrong with the way we are living—but we can fix that. We need to realise—we are not medieval peasants begging at the table of King Musk and King Zuckerberg for a few little crumbs of attention from their tables. We are the free citizens of democracies, and we own our own minds—and we can take them back if we want to.

Rebecca Schwartz: Johann, thank you for this conversation. We at Porchlight cannot recommend Stolen Focus highly enough. It’s enormously readable and vitally important to us all.

Johann Hari: Thank you so much! I am thrilled by your support and really grateful for it!