Books to Watch | June 8, 2021

Each and every week, our marketing team—Dylan Schleicher (DJJS), Gabbi Cisneros (GMC), and now Emily Porter (EPP)—highlights a few new books we are most excited about.

This week, our choices are:

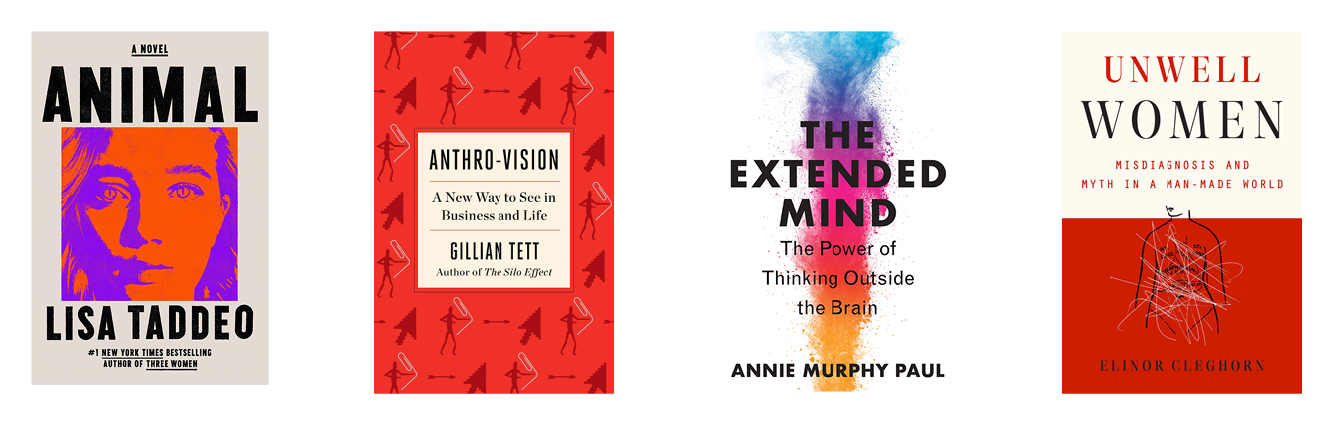

Animal by Lisa Taddeo, Avid Reader Press

After writing her bestselling and unsparing nonfiction narrative of women and sex, Three Women, Lisa Taddeo brings another riveting story to the masses with her novel Animal. The protagonist, Joan, is a complex character who has experienced a life of suffering. After a traumatic and fatal “break up” with her unstable, obsessed boss, Joan escapes to the sunny skies of California to face the truth of what happened to her when she was little through a young woman named Alice—the one person in the world who can help with making her feel whole. The backstory that leads her there is emotional, and often troubling—a reminder that being a woman in this world can be difficult for many reasons, and what, when taken to extremes, that can do to an individual.

Through abuse, trauma, and negative sexual experiences and relationships, Joan has developed dark views toward men and a skewed perspective of how the world works. As a 30-something woman, she navigates through her life trying to find any scrap of love offered with no satisfaction or conclusion to her overwhelming need. Wandering through life believing her sexual prowess is her one advantage, she finds herself falling into bed with the seediest of men, the only kind she seems to be drawn to. A tale of survival, her story reveals what trauma and negative cycles can do to a person—how the rage it builds can seep to the surface. Through messy affairs, violence, and constant moves, Joan tries to find what she is looking for without knowing exactly what that is due to the impressions of her troubled past.

Animal reminds us that everyone has a story, and that everyone is seeking love, even if they don’t always know how to seek it in the healthiest of ways. A wild read to say the least, I had so many thoughts and feelings arise after completing it, and it was a book I couldn’t put down so that happened fast. Weaving through the pages of this woman's life, you begin to understand how Joan came to be—maybe how any woman could come to be Joan. It is a story not often told, or not told often enough, or with enough understanding, made addictive in this case through Taddeo’s powerful writing style so that we’re compelled to listen. (EPP)

Anthro-Vision: A New Way to See in Business and Life by Gillian Tett, Avid Reader Press

We are having a reckoning with the role of experts and expertise in our world today. Some of it is dangerous, such as when it undermines our ability to accept and adhere to verifiable facts in our largest, most contentious, and important debates. But some of it is well-earned, as studies have shown that experts aren’t any better at making predictions based upon those facts—even in the area of their expertise—than the average person (and the average person isn’t very good at making predictions). It is why an event like the Great Recession, which seems perfectly predictable in hindsight, was not predicted by more experts. One person who did predict it was award-winning financial journalist Gillian Tett, and it may have something to do with her fieldwork studying marriage rituals in Tajikistan—not because they are related in any way, but because of the mindset and tools she learned as an anthropologist, and how it shaped how she sees the world.

Tett’s 2015 book, The Silo Effect, turned an anthropological lens on organizational silos and how they can be broken down to incubate ideas across different disciplines and unleash innovation. Her new book, Anthro-Vision, broadens those lessons to “the need to make the ‘strange familiar,’ to make the ‘familiar strange’” in every aspect of our life and work.

These ideas are as useful in making sense of an Amazon warehouse as in an Amazon jungle.

Tett encourages us to use a new AI—anthropology intelligence—alongside big data, social science alongside computer science, to uncover what we’ve become blind to and overcome our pre-existing biases. Rather than abandon expertise or science, we can embrace it by broadening it, develop lateral vision instead of tunnel vision. and learn more about each other and about ourselves in the process. (DJJS)

The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain by Annie Murphy Paul, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

There has been an explosion of advances in brain science in recent decades. Discoveries of the brain’s neuroplasticity, specifically how it continues to develop and evolve even as we age, have been some of the most exciting in the field—and perhaps for us as individual human beings. But, as Annie Murphy notes in her new book:

Much less attention has been paid to the ways people use the world to think: the gesture of the hands, the space of a sketchbook, the act of listening to someone tell a story, or the task of teaching someone else. These “extra-neural” inputs change the way we think; it could even be said that they constitute a part of the thinking process itself. But where is the chronicle of this mode of cognition?

(Hint: If you’re reading this, you’ve found it.) Because here’s the thing: for all the advances in our understanding of the brain, “The less heralded story of the past several decades,” Murphy Paul believes, “has been researchers’ growing awareness of the brain’s limits.” And, even as we’ve learned more about how our brains function, we seem to be using them less, as “Truly original ideas and innovations seem scarce; engagement levels at school and in companies are low; teams and groups struggle to work together in effective and meaningful ways.” We seem to fall prey to falsehoods and conspiracy more easily, and to let our many cognitive biases undermine us. That is where advances in the study of embodied cognition, situated cognition, and distributed cognition can help. To do our best thinking, it is just as (and maybe even more) important to get out of our own heads as it is to understand how the organ inside of it works. Yes, learning about how our brain works, and how we can improve how it works, is exciting. But that improvement is, as Murphy Paul notes, limited—both by its own power and to the individual in which it resides. If we can learn to think more with the world around us, to tune into the intelligence in our own bodies, in our environments, and in our relationships and interactions with others, it extends beyond ourselves as individual humans to humanity and the world around us. Understanding, extending, and improving our overall cognition in this way might even lead to us extending our hearts more easily to others, to an explosion of understanding and empathy, and that might just make all the difference. (DJJS)

Unwell Women: Misdiagnosis and Myth in a Man-Made World by Elinor Cleghorn, Dutton

I’ve been a very health-conscious person since high school, but reading Unwell Women by Elinor Cleghorn makes me question how much my ideas of female wellness have been skewed by gender inequality and sexism.

The simple fact that a sexist system has been surreptitiously controlling whether women lived, died, or suffered in any way from illness is difficult to come to terms with; A more inclusive and equal healthcare system could have saved a loved one’s life.

Women are more likely to be offered minor tranquilizers and antidepressants than analgesic pain medication. Women are less likely to be referred for further diagnostic investigations than men are. And women’s pain is much more likely to be seen as having an emotional or a psychological cause, rather than a bodily or biological one. Women are the predominant sufferers of chronic diseases that begin with pain. But before our pain is taken seriously as a symptom of a possible disease, it first has to be validated–and believed–by a medical professional.

Women have fought and continue to fight to gain autonomy and independence in the world, but the centuries deep history of androcentrism in medicine (and the world in general) is hard to redirect. In Unwell Women, Cleghorn thoroughly explains the history of medicine–from the sex-shaming male physicians of the 1800s, to the health campaigning feminists of the ‘60s and ‘70s like Perkins Gilman whose efforts have made the contraceptive pill and hormone replacement therapy safer, to the modern-day efforts by everyday women who are unabashedly speaking about their own bodies in order to help other women who are still being ignored or invalidated by the healthcare system. The throughline is that, historically, women have been defined by their biology, namely their uterus and ability to bear children. Unwell Women makes a strong argument for medicine to look beyond biological evidence and communicate with and listen to those who know women’s bodies best: women themselves. (GMC)