Inside the 2022 Longlist | Narrative & Biography

We hand out a Jack Covert Award for Contribution to the Business Book Industry every year. I also like to keep Jack, who passed away last year, in my mind while reading all the books that are submitted for the awards. My personal tastes didn’t align exactly with Jack’s, but there was a good deal of overlap, and a love of narratives and biographies was one of those places. And, if there is a theme in the Narrative & Biography category this year, it is that of place. I sometimes worry that our business book awards are leaning into anti-business sentiments, or at least that they may be viewed as such—that we’re losing our place. But then I remember the wonderful work that Fast Company did in expanding what a business magazine could be, and that the best business book publishers are doing in what constitutes a business book. I remember that the best business books are often not those that act as boosters for business, but that challenge business to do better and show us how. If there is one thing we’ve learned over the past three years (which may be ambitious) it’s that business-as-usual and the way we work hasn’t been working for many, if not most, of us. Finding a better way, and fixing what’s broken, is the most proactively pro-business thing one can do.

So, what can the Narrative & Biography category contribute? Like fiction, it can help us empathize with and even inhabit, for a brief moment in the pages of a book, the mindsets and experiences of other people. It allows us a peek into the lives of individuals, to see inside organizations, and visit other places without having to leave the comfort our reading chair. Some of those places we might be visiting for the first time, and others may feel familiar, even nostalgic. All of them help us consider our own place in the world.

These are the five books I most enjoyed travelling through this year.

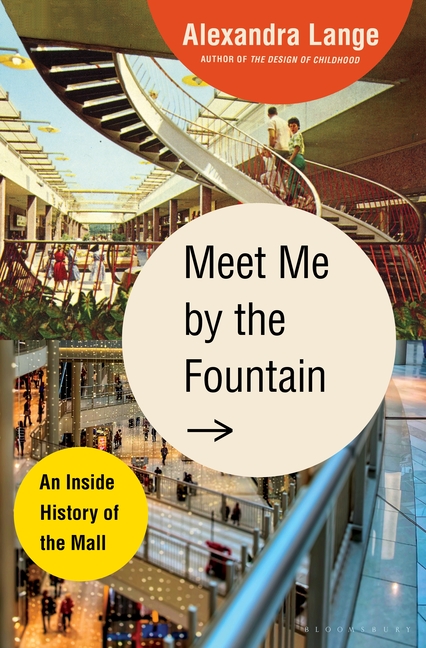

Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall by Alexandra Lange, Bloomsbury Publishing

Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall by Alexandra Lange, Bloomsbury Publishing

Long before Twitter made a claim of being a digital town square, the “town square” most of us gathered in had already migrated into another privately owned commercial space—the shopping mall. Most of us can name the malls we grew up going to. My first were Cherryvale and Machesney Park in Rockford. When we moved to Wisconsin, we found malls that were named, like so many others across the country, after the cardinal directions—Northridge, Southridge, with a Brookfield Square thrown in out in the (then) exurbs of Milwaukee. Gurnee Mills was a big deal when it opened, and then suddenly not such a big deal just a few years later as people started shopping more online. Mostly, from all those places, I remember the magic of indoor trees and tossing coins in sparkling fountains.

Meet Me by the Fountain is certain to bring back similar memories of the malls you’ve frequented, but it is not (only) a nostalgic look back at a bygone era. It is, by its end, both a deep history of the shopping mall and a bold reimagining of what their future could be. Lange accomplishes that in part by looking at what they’ve become in other places around the world. But she also looks at what they were designed to do in the past, and where they came up short. Did the department store that led to shopping malls also lead to some amount of women’s liberation? Did the evolution of department stores into shopping malls divide us, bring us together, or both? Before big box stores and the internet, the mall was the apex of consumerism, but it was also a place to come together. As the ubiquity of automobiles led to the suburbanization of America in postwar America, malls were invented as the new place to gather, and:

With that came worldly expectations, still unmet, that the mall might replace the Main Streets it sent under.

By the end of our time with Alexandra Lange, we’re not only longing for a trip to the mall, but are left with the conviction that the mall might have a lot of life left in it. And, as we learn in our next book, maybe even “the Main Street it sent under” does, as well.

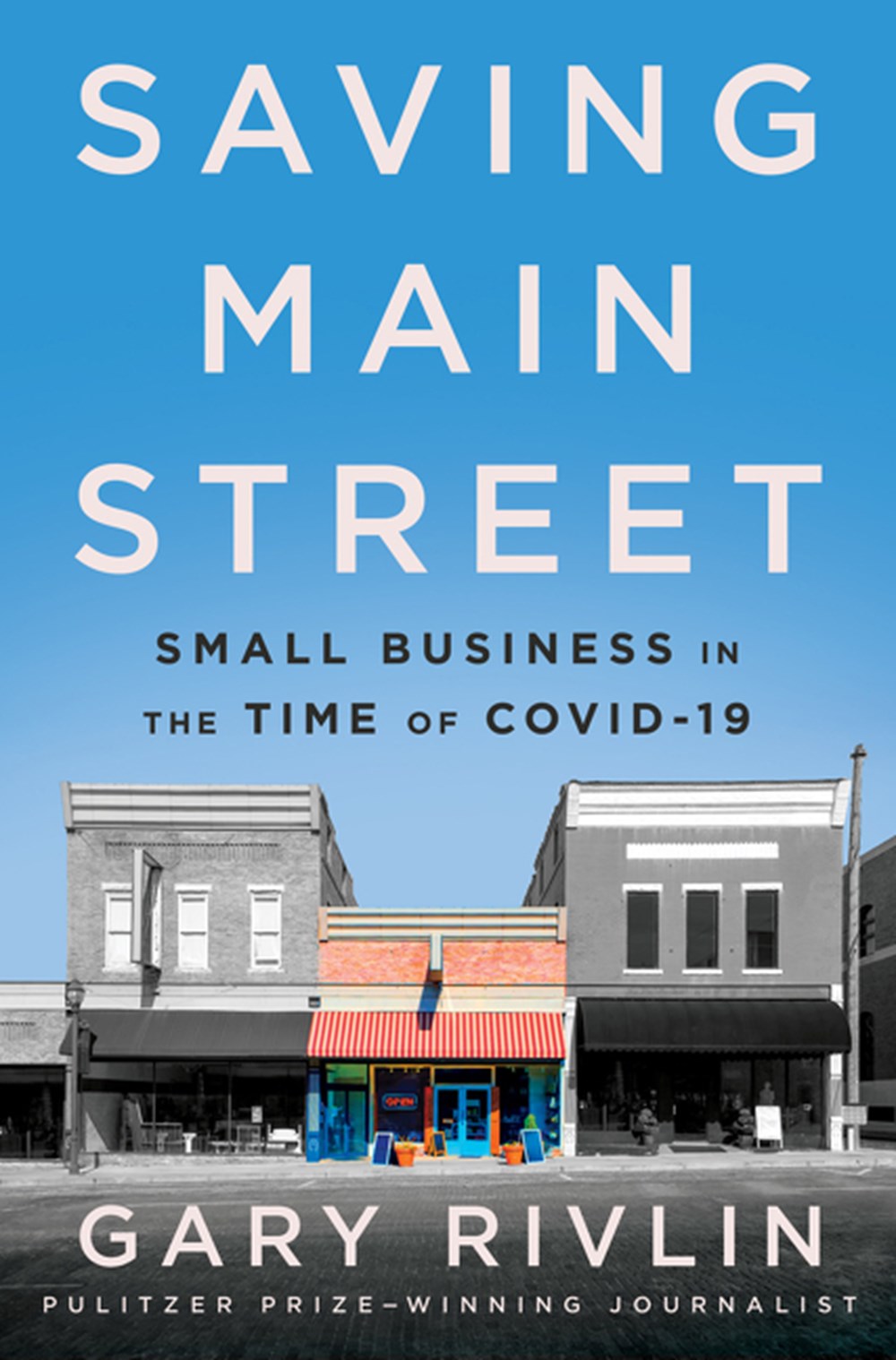

Saving Main Street: Small Business in the Time of COVID-19 by Gary Rivlin, Harper Business

Saving Main Street: Small Business in the Time of COVID-19 by Gary Rivlin, Harper Business

The people and businesses Gary Rivlin profiles in Saving Main Street are the kind we often describe as the backbone of America. After reading the book, I am beginning to think of them more as the faces of a certain slice of America. Like those with a little age on them, these faces have a lot of character, and it is that character—of small-town and neighborhood businesses and businesspeople—that makes places unique. Proprietor-owned, perpetually on the edge of financial stability, they are the kind of small businesses that were decimated by the pandemic: an Italian restaurant, an independent gift and greeting card shop, and an immigrant-owned hair salon. There are other businesses featured, like a chocolate bar manufacturer started by three brothers in the South Bronx, but those three businesses—all three located in the northeastern portion of Pennsylvania around Scranton—are the ones Rivlin focuses on.

In a battleground state at a time when a presidential election featured one of their native sons and dominated the news and airways, politics are inescapable. That is even more true because public policy during the pandemic affected their business’s prospects so directly. But Rivlin doesn’t get too bogged down in them, or at least not any more bogged down in them than the business owners themselves do. So you get to know the politics of the place a bit, but you really get to know the “Goldilocks” character (“not too big, not too small”) of places like Old Forge and the people who populate them. You get to know, rather intimately, the lives and business of those who do so much to provide a unique sense of place in those communities. It is not glamorous. It is a life of long hours and hard work, and it’s not usually as lucrative as other options they could pursue. But those with the passion to pull and hold these kinds of operations together make something more memorable for all of us than the chain restaurants and big box stores on the edge of town.

In the stories of their hardscrabble survival, we find some hope. In places like theirs, we find community. It has always been so, all over America.

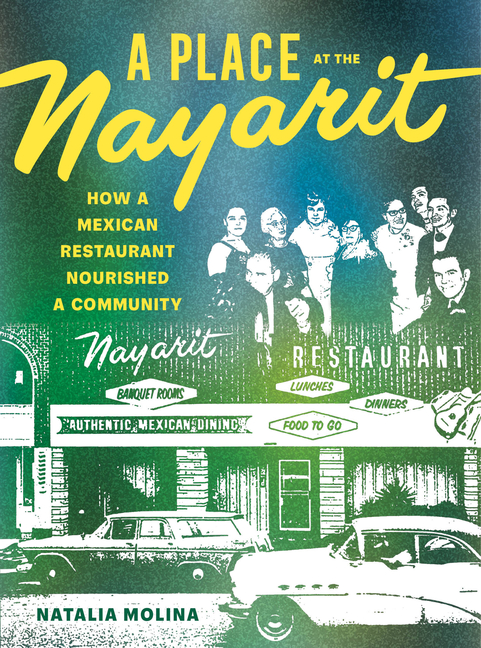

A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community by Natalia Molina, University of California Press

A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community by Natalia Molina, University of California Press

The place featured in Natalia Molina’s book is a restaurant called the Nayarit. But that place is also Echo Park in Los Angeles, and the state of Nayarit in Mexico that the restaurant was named after. And it is a place where immigrants and the LGBTQ community are able to find refuge, feel safe, and feel free to be themselves. It was a place people could speak in their mother tongue, even though it wasn’t entirely an ethnic enclave. The Nayarit attracted people from all over the area—businesspeople from downtown for lunch, laborers from the neighborhood for dinner, and late-night revelers looking for a late-night/early-morning meal to soak up the alcohol and the time before heading home—yet it defined one area of Echo Park in particular. It was, and remains to many, a landmark, even though it no longer exists.

The woman who opened the Nayarit, Doña Natalia, happens to have an extremely erudite academic and author as a granddaughter that she never met to tell the story of the restaurant and neighborhood it was anchored in. It is in some ways about what we have lost: the restaurant itself, the residents who can no longer afford to live in the neighborhood they grew up in because of its gentrification. But it is also about what can be gained when we embrace not only where we come from, but where we’re at, and where other people in that place are coming from.

Doña Natalia’s decree that her relatives and employees visit different parts of town—that they become place-takers—was a prompt to be daring, even to subvert the status quo. Though Nayarit workers may not have been trying to challenge social norms outright, venturing into the historically white neighborhoods of segregated Los Angeles must have required real bravery. The Nayarit’s gay employees led the way.

Being told to stay in one’s place is oppressive. The feeling of finding one’s place in the world, and of daring to take up that space, can be liberating. Which brings us to our next book, by a fellow Angeleno.

Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop by Danyel Smith, Roc Lit 101

Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop by Danyel Smith, Roc Lit 101

Shine Bright is a brilliant book. It not only tells the stories of the Black women whose intelligence, talent, and drive have defined the music that's become so much of what constitutes American culture, but it is also a memoir of the masterful artist at work in its pages. It is brilliant in the sense that, now that I know its contents, the book seems to glow on my bookshelf and beckon me back to reread portions of it. As she tells us the tales of the Dixie Cups, of Dionne Warwick and Cissy Houston, of Leontyne Price and Linda “Peaches” Greene, of Janet Jackson and Mariah Carey, author Danyel Smith also recounts the struggles and successes of her own life and career, which saw her rise to become the first Black and first woman editor in chief of Vibe. The very conceit of the book, to interweave her own story with the history of Black women in music, is mind-bogglingly ambitious, and she pulls it off with aplomb. In the book’s Outro—a great term I’d never encountered outside of ‘90s hip-hop albums before—she even hints at some insane-sounding stories from her life and career that she didn’t include that seem like they could fill an entire book of their own. And I selfishly hope they do fill a book some day because I want to read more. Smith also writes of the anxiety she experienced in bringing the book to a conclusion, and how “so much of Black women’s work is undervalued and strategically un-remembered.” I hope people find their way to this book for that reason, but also because it is a business book in the best sense of the word—about a remarkable individual's work and career, about an industry that has not done well historically by those who create the product that produces the wealth, and about the women who have created so much of American pop culture.

I also had to pick this book for our company because we’ve always had a connection to music here. Our founder, Jack Covert, ran a record store in Milwaukee before David Schwartz hired him to run the business book section of the local Harry W. Schwartz Bookshop, which would eventually become the company that exists today as Porchlight. One of our longest-tenured people’s spouse runs Milwaukee’s best record store today, and we’ve always had a lot of working musicians and writers who wrote about music employed in the company. So this book beckoned to me even before I opened it up and found out just how brilliant it is. At its core, though, it is about the music, a place in which so many of us have found ourselves, forged our identity, and in Danyel Smith’s case, constructed a career.

Milked: How an American Crisis Brought Together Midwestern Dairy Farmers and Mexican Workers by Ruth Conniff, The New Press

Milked: How an American Crisis Brought Together Midwestern Dairy Farmers and Mexican Workers by Ruth Conniff, The New Press

I don’t think Thomas Wolfe’s posthumously published novel, You Can't Go Home Again, is very widely read, but it gave us the old adage that “you can never go home again,” which is very widely said. Well, we’re ending this category write-up by going home again—to Wisconsin, the place at the center of Milked.

I lived on a dairy farm for a few years when I was young, and my mother grew up on one. She speaks about the old house without running water, and the two brothers and four sisters, mom and dad and uncle who shared it, all of whom helped on the farm. It sounds like a lot of people, but they were one of the smaller farming families in the area, all of whom would come together to help each other out around harvest time. Today, after decades of consolidation and corporatization that has led to a drastic decline in the number of family farms, more space between them, smaller family sizes, and the exodus of the next generation of farm families to more populated areas, there is an acute shortage of farm workers, which has brought an infusion of workers from Mexico north. Ruth Coniff’s Milked explores how that is playing out in America’s Dairyland. In many ways, the values and culture of rural Mexico and rural Wisconsin are aligned, but the power structures and racial politics of (often undocumented) immigrants' existence in Wisconsin can be perilous for them. It breaks my heart, because my own family started as immigrant farm workers in this state, and because I think an infusion of immigrants could build a new generation of family-owned farms here. Also because, as Conniff writes:

If Mexican workers’ relationship with the United States is a relationship of dependency, the dependents are not immigrants coming illegally to the United States to live off hardworking taxpayers, as some U.S. politicians claim. The real dependents are U.S. employers, as well as Mexican communities … that survive on migrant labor. Undocumented workers are carrying the economies of both places on their backs.

Speaking of going home again, the book ends in the mountains of Mexico, where one of the families featured in the book returned to. I admire the journey they made and envy the idyllic setting this family has finally settled in. I also hold out hope that some of the immigrants who’ve arrived here will stay on and own family farms in Wisconsin, that they will make a home here and continue a way of life the state has known for generations.