Any Kind of Woman

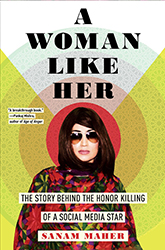

I spent this past weekend with a sore back and the stories of two famous women tangling in my head. Forced off my feet while I iced my injury, I read A Woman Like Her, a biography about Qandeel Baloch, a Pakistani social media sensation who was murdered by her own brother for dishonoring her family, written by Sanam Maher and recently published by Melville House. And in between bouts of reading, I streamed the new Netflix documentary on Taylor Swift, Miss Americana.

I spent this past weekend with a sore back and the stories of two famous women tangling in my head. Forced off my feet while I iced my injury, I read A Woman Like Her, a biography about Qandeel Baloch, a Pakistani social media sensation who was murdered by her own brother for dishonoring her family, written by Sanam Maher and recently published by Melville House. And in between bouts of reading, I streamed the new Netflix documentary on Taylor Swift, Miss Americana.

While the life stories of Taylor Swift and Qandeel Baloch could scarcely be more different (and I’m not trying to equate their circumstances or trajectories here), there are similarities worth studying as women continue to pluck away at the constraining knots of patriarchy and simultaneously weather the often-outsized backlash to that slow unraveling. The common element between Swift and Baloch is not just their presence in pop culture, but that they have been openly ambitious and worked very hard and very publicly to gain fame to satisfy that ambition. But as we’ve learned from several recent political candidacies, and, well, all of history, there is little a patriarchal culture likes less than an ambitious woman. Swift, even with all of her privileges, acknowledges a certain shelf life to that success simply because she is a woman, a woman soon to be 30 and thus, she has witnessed, soon to be unfavorable to the men who control the portals to fame: “I want to work really hard while society is still tolerating me being successful.” Baloch was punished for her ambition in a culture that was specifically unwilling to tolerate her, full-stop, and as a result died long before she could even turn 30.

During my day of reading and streaming the lives of these two women, the refrain from Anne Sexton’s poem, Her Kind, began to play in my head. A woman like that…. I have been her kind. A lean poem of three stanzas, Sexton paints the portrait of a woman, an everywoman, in three historical scenes. Woman as witch on a broom. Woman as witch in a cave mixing potions. Woman as witch taken to her death by fire or wheel. She is skillful, changeable, multi-dimensional, but ultimately she is punished for her selfhood—the only end is death.

Qandeel Baloch, born Fouzia Azeem, grew up in a small village where she envied her brother’s freedoms and yearned for fame. Maher describes Baloch as a child, standing in front of the family television and pretending to dance and sing, knowing at a young age she wanted to be a star. But any path to fame was unmarked as she was limited by her circumstances and had few role models to emulate. Throughout the book, the author interviews people who knew Baloch or worked in similar jobs or frequented the same social circles to paint a fulsome picture of the mountain Baloch had to climb in order to get even a taste of success, and the decisions she made to begin and then sustain her ascent. Maher includes quotes from Baloch to give her ownership over her story. “I tried a lot. I didn’t want to move forward in this industry the way other actresses move forward. Everyone knows what they get up to behind the camera. At least I’m better than that.” But small acting roles never led to long-term contracts, provincial modeling gigs in malls never amounted to getting booked for shows in larger markets, opportunities never led to more opportunity.

Baloch was limited by her circumstances—predominantly the country she lived in, but also the family she was born into. “‘These people are bigger than you,’ [her mother] remembers saying ‘Don’t meet these people who are above your stature,’ she cautioned. Remember where you come from. Whose daughter you are.” At the same time, Baloch was freed to reach beyond those limitations due to the internet. Social media allowed Baloch to create an online persona that demanded attention. She was risque and outspoken. She was creative, uninhibited. She was not your typical Pakistani woman. And, it seemed, some of her critics stopped seeing her as a woman at all.

A woman like that is not a woman, quite.

I have been her kind.

With hundreds of thousands of online followers, Baloch got the attention she craved, but that attention was often abusive, laced with vitriol and death threats. When she dared to speak out about a cleric, alleging misbehavior, those in power leaked her personal information, and that exposure incited her critics to spread their abuse to her village, her family. Perhaps she first thought it a temporary dust-up that would resolve as so many had, underestimating the impact of making a cleric her enemy, of symbolically but loudly provoking the state. ‘“Don’t think badly of me,” she told her father. “I haven’t done anything wrong. I’m just fighting with someone.”’ But it soon became clear that she had crossed a line by engaging with a prominent religious figure: I’m telling you that my life is in danger and you’re accusing me of a publicity stunt? Ultimately, it was her own brother who began to believe that she had finally crossed the line. Baloch had brought shame to their family and he believed it was his right and obligation to punish her. He believed he had no choice, for the sake of his family and his religion and his country. She needed to be stopped.

A woman like that is misunderstood.

I have been her kind

The documentary Miss Americana intertwines three timelines in Taylor Swift’s professional life: her easy but repressive teenage country fame, the infamous Kanye beef, the sexual harassment lawsuit that made her a target of rampant social media abuse, and finally the catharsis of writing and recording her most recent record, Lover.

While Swift’s rise to popularity and the endurance of that fame features few of the dangers of Baloch’s, the documentary does show that growing up under a microscope, and within the narrow parameters society allows women, is a gauntlet all its own. Before stepping on stage for a tour performance, as a way to boost her confidence, Swift tells herself, “no one out there actively hates me.” She is so used to everything she does being met with criticism and bile, that it becomes rare for her to feel a sense of security.

Certainly we understand that the biggest difference between Swift and Baloch is their actual security, but fear plays a very real part in their every interaction with the public. And really how secure is Swift? She throws out this fact mid-documentary, not even bothering to note how dangerous the situation could have turned: “I had a crazy dude break into my apartment and sleep in my bed a couple months ago.” The line between security and peril is indeed fine. By the end of the documentary, Swift is a better—braver, louder—version of herself in spite of her wariness: “I want to love glitter and also stand up for the double standards that exist in our society. I want to wear pink and tell you how I feel about politics. And I don’t think those things have to cancel each other out.” While that statement may seem frivolous within the context of the suffering of women who are denied their lives as a result of speaking out and taking risks, I think Baloch felt similarly. She wanted to be beautiful, creative, and unlimited.

But navigating a path through the fickle nature of attention isn’t easy. Swift says that her critics want her to “live out a narrative that we find to be interesting enough to entertain us but not so crazy that it makes us uncomfortable.” She is conscious of the need to constantly reinvent herself while also keeping her creations within a certain set of parameters. Baloch was not able to walk that line. She told her story in attention-seeking extremes. At its peak, her fame culminated in becoming a social media influencer—sexy poses, bikinis made to resemble the Pakistani flag, suggestive promises, and songs sung from her bed—and it made her critics who watched both entertained and deeply uncomfortable. But Baloch seemed aware of the line Swift speaks of: I used to make funny videos just to make people laugh. People would abuse me so much I would wonder, What have I even done? When they say you are so bad, then you might as well become bad. Ultimately we do learn from Miss Americana that even if you’re Taylor Swift, you can never be the kind of woman an entire country wants you to be. And in A Woman Like Her, we learn that a woman like Qandeel Baloch was everything her country didn’t want her to be.

Any loss of popularity that Taylor Swift might experience just because the entertainment industry is fatigued by her success and intolerant of her growth is of course nothing compared to the extremism of Baloch’s “punishment” for pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable for Pakistani women. But neither of these women’s behaviors should prompt abuse. The next question that must be asked when we hear about any woman who is abused for being her ambitious self, regardless if it’s by online trolls or human hands, is why? Why is it such a critical loss for men that they react in anger and violence when a woman defines herself for herself, lives her life as defined by herself? Sexton wrote in the final stanza of Her Kind:

I have ridden in your cart, driver,

waved my nude arms at villages going by,

learning the last bright routes, survivor

where your flames still bite my thigh

and my ribs crack where your wheels wind.

It has always been this way, Sexton seems to be saying in Her Kind. A woman dares, and the patriarchy strikes back because its power is only sustained when women are kept powerless.

[Sexton, it must be noted, was revealed to have sexually abused her daughter. One of the realities of our current culture is grappling with the art made by people whom we know have committed atrocities against the vulnerable. How we respond is fraught with risk. We can choose to omit these artists from our histories and boycott their work. We can stubbornly declare an artist’s work stands alone from their behaviors as a person and refuse to deny ourselves the pleasure of their art. Or we can find a middle way, acknowledging that the co-existence of an artist’s work and an artist’s life is tricky and uncomfortable, but we will engage with that discomfort because it informs our understanding of humanity and art rather than ignores the deeper discussion. I am choosing the latter here. Sexton’s poetry speaks to the powerlessness of women to craft their own narrative, and our engagement with it forces us to reckon with the darkness of her behaviors in the same way we reckon with the darkness of any abuser.]

It is a tragic irony that Qandeel Baloch’s fame has skyrocketed posthumously. Before her death, she wrote: “I’m a girl power. So many girls tell me I’m a girl power, and yes, I am.” Swift might say the same about her own influence to inspire her fanbase to make change in the world: “Resist. If you can just shift the power in your direction by being bold enough, then it won’t be like this forever.” Perhaps Baloch understood that the abuse she was taking for her boldness might lessen the abuse other women who take risks and pursue their dreams might endure. And Maher makes it clear that Baloch’s legacy has changed with her death, and is now shaded with martyrdom. “These words may have been ignored had Baloch lived. Today they serve as a rallying point for those who defend her choices. In death, she has been adopted and praised by women who enjoy the security she craved and hoped to attain with enough money, enough fame.”

A woman like that is not ashamed to die.

I have been her kind.

The differences between Taylor Swift and Qandeel Baloch’s experiences are vast. Ethnic culture, religious culture, economic and psychological safety, family support, the list is long. And of course, Taylor Swift is alive to tell her story, to continue to craft her story and her life while Baloch is not. But whether written or filmed, whether historic or current, we need to keep telling and hearing the stories of complex and complicated women so that someday a woman can feel fully free—free from limitations, free from abuse, abuse that registers anywhere on the continuum of abuse—to be any kind of woman she wants to be.