The Best Narrative & Biography Books of 2024

How did we get here?

By “here,” I mean the current state of the world—one in which loneliness is deeply entrenched, in which we have grown more polarized and divided than ever before, in which exercising empathy feels exhausting and fruitless. Perhaps it was the presidential election bisecting our awards reading season and the sense of an impending fundamental shift in the status quo that had me searching for an answer to this question. I’m a lifelong student of history with a deep belief that to understand the present, it always does well to peer into the past.

There is, quite simply, a lot going on these days. The political has become personal, the private has become public, vice versa, et cetera, ad infinitum. The writer James Baldwin once declared, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” Yet, with so much going on all at once, what should one choose to face first?

Think of each book in this year’s Narrative & Biography category as the end of a thread waiting to be pulled to help unravel the ball of yarn that is the current state of the world. You’ll find that everything is interconnected, that everything that feels like a modern-day predicament has its roots in happenings that began generations ago. The stories told here can be hard to take in, with no happily ever after in sight, but they will all have an indelible impact on how you see the world around you. To quote the author and professor David Shih, “Reading a book is not an afternoon under the shade of a tree. It is splitting wood, hard work. Something is at stake for you.”

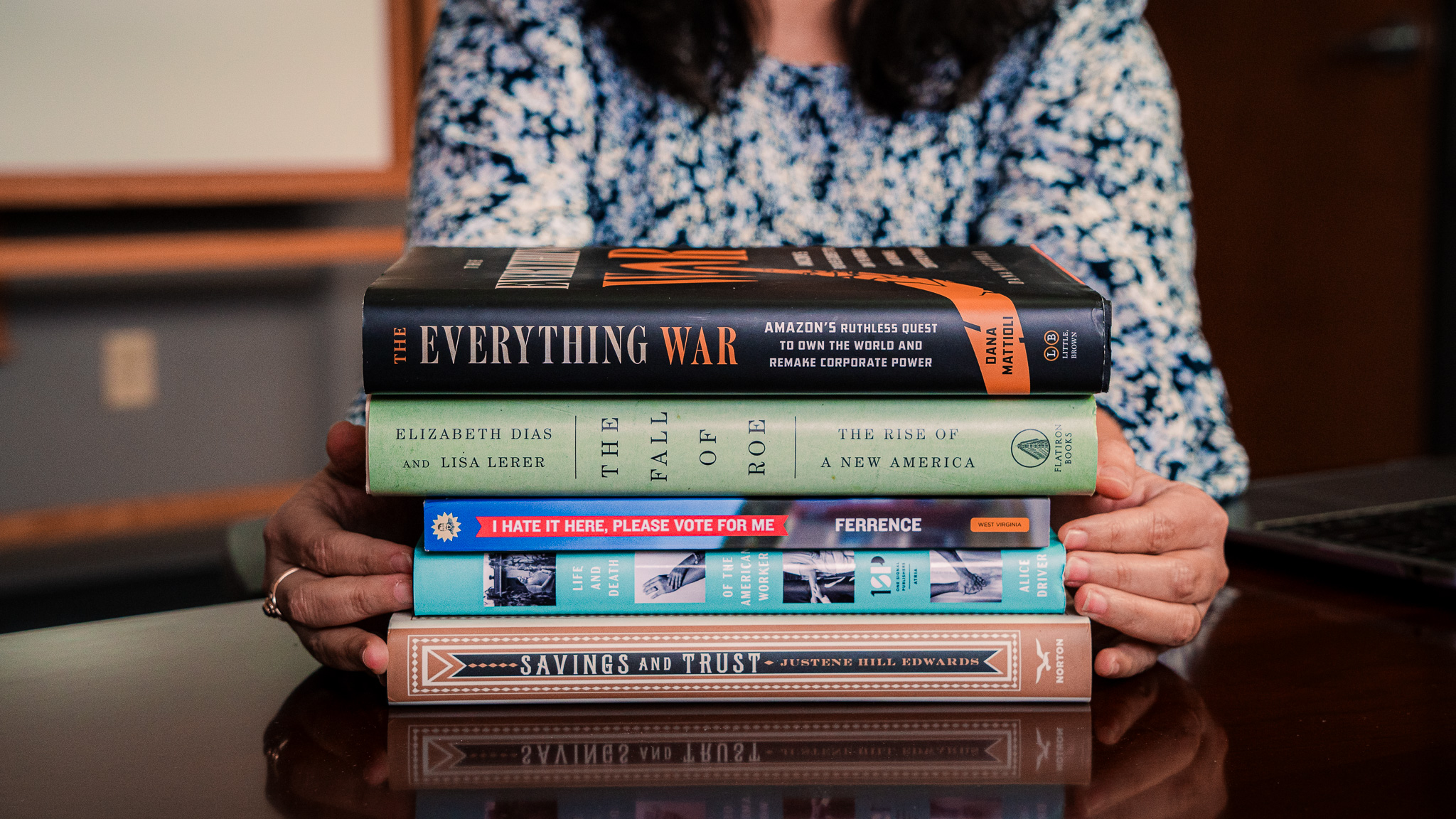

The Everything War: Amazon’s Ruthless Quest to Own the World and Remake Corporate Power by Dana Mattoli, Little, Brown and Company

“There was a common mission among many of the early employees to democratize reading,” Dana Mattoli writes of the first people who worked at Amazon. Among that first group were writers, academics, and music lovers embedded in Seattle’s nascent grunge scene. Amazon, then, was a threadbare website on the burgeoning internet, a simple portal between the nation’s largest book distributors and shoppers who might not have easy access to a brick-and-mortar bookstore.

This vision of what Amazon might have been feels quaint today, even laughable. Perhaps, under someone else’s leadership, Amazon would have moved forward with such a bohemian ethos, finding its niche in the book world alongside neighborhood shops and filling the gap of getting books to remote places. Yet, as Mattoli reveals through her deeply researched narrative, founder Jeff Bezos chose books as a simple entry point for his new endeavor. It was never about a genuine passion for books or even for profits, as with any other retail business. Rather, the goal has been conquest.

With each new category it expanded in, Amazon chose growth over profits. Those gains often came at the expense of its rivals. It was seen as a zero-sum game. For every item that Amazon sold in the new categories it entered, it meant a loss from a physical store that merchandised that item

It is virtually impossible these days to avoid interacting with any part of the Amazon ecosystem. Even if one forgoes shopping through Amazon or consuming its entertainment offerings on Prime, the company has transitioned from simply existing on the internet to powering it through its Amazon Web Services subsidiary. It has acquired other existing companies, from MGM Studios to Whole Foods to Zappos and more. It has surpassed UPS and FedEx as the nation’s largest nongovernmental parcel carrier, to the point where many small business owners have had to embed themselves in the Fulfillment by Amazon network to find their foothold in the marketplace. Amazon offers to be everything to its customers: a bookstore, a movie theater, a grocery store, a shopping mall, even a doctor’s office and pharmacy. Everything that required us to go outside, to interact meaningfully with others, can now be done with a single click of a mouse, tap of a screen, or request posed to an Echo device, from the comfort of our homes, with no human contact needed.

But is this an existence that truly benefits us? And at whose expense has it all been built?

Amazon’s meteoric rise hasn’t come from the grassroots—that is to say, it has not been a simple matter of consumers choosing to turn to Amazon because it offers the best goods and services. Mattoli uncovers multiple instances of the company steamrolling competitors and partners alike, including selling diapers at a loss to undercut e-commerce company Quidsi, or meeting with the creator of the Ubi device under the guise of acquisition, only to turn around months later with their own carbon copy, the Echo. She notes that, in its early days, Bezos believed Amazon could function alongside the original one-stop shop Sears as its digital equivalent—instead, Amazon’s gaming of tax loopholes led companies like Sears, Toys “R” Us, and JCPenney, all suddenly unable to compete for buyers’ dollars, to file for bankruptcy. This is hardly the healthy competition and availability of choice that free market capitalism has promised, but rather the imposition of one man’s vision upon the rest of the world.

This isn’t an elegy for the corporations themselves, per se, but rather, the intangibles that we lost when these mainstays, along with all the smaller mom-and-pop shops that operated alongside them, suddenly shut their doors, unable to compete with the Amazon behemoth. Mattoli writes:

The act of shopping in person created a community in local towns. Main Street store owners knew their regular customers by name; they sponsored local Little League teams and holiday events and employed members of their communities. Healthy traffic and revenue to these stores buttressed local real estate developers and landlords. The money recirculated within the towns and cities through the local merchants, and they also generated sales taxes for local projects and school systems. The relationship was symbiotic

Much like a flywheel keeps spinning from its self-generated inertia, Amazon’s expansion further powers Amazon’s expansion—the bigger it gets, the bigger it seemingly needs to get. As Mattoli writes about the company’s increasing involvement in the political sphere:

When it was a nascent book retailer, Amazon didn’t need much lobbying power. What was most important during that phase was preserving its sales tax advantage. But as Amazon expanded into other categories and other industries, spreading more and more tentacles, it would soon recognize that it would require much more of them on the lobbying front than the narrow scope it had focused on

Amazon’s political involvement has kicked off a long and bitter legislative battle, touching everything from antitrust laws to fair labor practices. In late 2023, the Federal Trade Commission under Lina Khan sued Amazon for “maintaining an illegal monopoly.” The antitrust lawsuit is still in progress as of the book’s publication, and how it will unfold remains uncertain. Amazon, Mattoli writes, has “already done so much to reshape our daily lives and upend the economy; it’s transformed Main Street and how we behave.” It may yet change the foundation of our democracy.

The Fall of Roe: The Rise of a New America by Elizabeth Dias & Lisa Lerer, Flatiron Books

The Fall of Roe reads like a thriller. New York Times correspondents Elizabeth Dias and Lisa Lerer take readers back to the heyday of the Obama presidency, in which progressive politicians and advocacy organizations reveled in their electoral victories and in which many Americans made folk heroes out of pro-choice champions such as Wendy Davis and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. As in any good horror tale, the characters in this story feel safe in their surroundings, confident that no harm will ever reach them—they can’t hear us calling back from the future, imploring them to turn around and spot the threat lurking in the shadows. By the time they realize what’s happening, it’s too late.

The Supreme Court decision that came down in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in 2022, which effectively overruled Roe v. Wade, wasn’t the result of a sweeping change of heart across the United States—in fact, most Americans remain in favor of the right to legal abortions. Instead, it was the effort of a dedicated yet vocal minority movement that, as Dias and Lerer write, “did not think simply in electoral cycles.” Rather than undertaking the effort to change voters’ opinions on abortion rights, conservative activists took up a slow and steady strategy to chip away at Roe’s legal precedent and weaken abortion access from the grassroots.

Abortion opponents could not force America to embrace their belief that the first cell of a fetus deserved rights [...] But their cause could win anyhow if they could pass laws that banned abortion.

Efforts to roll back the legal precedent of Roe v. Wade, in which the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional right to an abortion via the right to privacy, were not new. Yet even as state legislative bodies debated and passed new laws restricting abortion access, “Democrats didn’t see the new state restrictions as a priority in a world with Roe.” Though it was part of the standard Democratic platform to remind voters that theirs was the party that would protect reproductive rights, the prevailing belief was that Roe was a permanent aspect of the American identity, a bulwark against any challenge to legal abortion.

In the end, the problem isn’t that the alarm never sounded, that the danger of Roe being overturned never made itself clear—it’s that the people in power failed to listen and to act in time. For example, activists of color had long pointed out that Roe offered limited protections so long as the Hyde Amendment was still on the books, which prohibited the use of federal funding for abortions and directly impacted low-income women insured by Medicaid. Although progressive leaders such as Nancy Northup from the Center for Reproductive Rights had proposed that Democratic members of Congress be proactive and codify abortion rights into federal law, the issue remained a low priority. Instead, organizations such as the Susan B. Anthony List recruited anti-abortion candidates to run for office, placing them in strategic positions to have an impact on future reproductive rights legislation. By the time Dobbs reached the Supreme Court, the bench was already stacked with conservative justices, and state legislatures were primed to pass even more restrictive laws in the decision’s wake.

This book serves as a reminder that nothing, bad or good, is ever fixed or unchangeable. This is both a cautionary message and a hopeful one. We can’t afford to become complacent and assume that things will just run on autopilot—whether it’s our laws, workplace cultures, or personal relationships. Building a better society requires continuous effort and ensuring that every voice—especially those different from our own—is heard and accounted for.

I Hate It Here, Please Vote for Me: Essays on Rural Political Decay by Matthew Ferrence, West Virginia University Press

In 2020, Crawford County resident Matthew Ferrence ran as a Democrat for a seat in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives against a Republican incumbent and lost. “A small consolation, I suppose, is that I outperformed all of the top-of-the-ticket Democrats, including Joe Biden,” he writes. “But I still got shellacked, badly.” This book, however, is not a retelling of that race.

Ferrence uses his doomed-from-the-start campaign as a launching point to shine a light on the rural Appalachian community he grew up in, which is often maligned and misrepresented or downright ignored by the broader progressive movement and by Americans writ large. This is not a book about political strategy—Ferrence argues that the workings of our two-party electoral system make meaningful political shifts virtually impossible. Instead, at its core, it is about what we lose when we turn away from one another.

Ferrence, a creative writing professor at Allegheny College, uses his craft as a lens through which to examine our current political divisions. We live in a vast landscape—geographically, certainly, but ideologically as well. Much of what we Americans know about one another comes from the stories we tell and are told. It certainly doesn’t help local news outlets have long suffered from budget cuts and closures, limiting the platforms available to elevate local voices that can provide a more truthful and nuanced perspective. As Ferrence notes,

Politics is at heart a literary problem, because politics relies, like so much else, on a shared belief in stories. Yet the verses of politics offer repetitions of trope, cheap flatness, tired old stories of utility that cast each of us into stable boxes from which we are not permitted to escape.

The mainstream stories we tell about rural Americans center heavily on negativity: racism, violence, drug use, poverty, a lack of education and sophistication. Even this region’s so-called best or hopeful stories have centered around economic production. As Ferrence writes: “The accepted social contract is that Appalachians live as embodiments of the resources exploited in their landscape. People and resources only matter as fuel for the prosperity of folks outside the region.” Think of any other marginalized group—people of color, immigrants, LGBTQ+ individuals, et cetera—and it’s easy to see how they have all been defined by stereotypes that have permeated through society. It is no wonder that as we continue to pass down these stories, resentment and fear of the unknown have only worsened.

Like the other books in this awards category, I Hate It Here, Please Vote for Me offers a look into the past—both the nation’s past and the author’s own—to understand what led to the state of the present day. Ferrence dives into the history of blue-collar labor, how farming, mining, and manufacturing served as the lifeblood for Appalachians until they suddenly couldn’t, a result of political maneuvering and corporate cost slashing that left rural communities abandoned and ravaged. He compares showing goats at the county fair and the win-at-any-cost mentality of electoral politics. He brilliantly argues that, deep down, we are all carrying the wounds of our high school days, that everything from Friday night football games to bullying to the growing pains of adolescence will, for better or worse, impact the adulthood we grow into:

Try looking at your own politicians through the lens of high school social order. I bet you see something. Try looking at the momentum of MAGA, the devotion to Trump, the now-overt hatred that consumes the GOP and is metastasizing from rural America to all of it, and think about how high school prepared us to accept this [...] In high school, we learn that violence and the consumption of bodies is our purpose in life. I don’t exaggerate. This is high school in the Rust Belt and Appalachia and the Midwest and the Northeast and across rural America. In high school, we learn it is better to punch first.

What this book also offers, however, is a glimmer of hope, a potential way forward out of the mess. Ferrence upholds beauty as an ideal to strive towards. The divisions between urban and rural, conservative and liberal, this or that, can feel like an uncrossable chasm. In truth, most of us aren’t prepared to leap across such a divide at this fragile moment. Ferrence writes, “The greatest travesty of politics is that it can teach us to hate ourselves, as in hating our whole self as individuals and members of a collective.” Building bridges may feel too challenging right now—to do so requires employing imaginations that have long been stifled. But we can start making progress by choosing each day to make our own little universes better, to let goodness and virtue radiate, and to begin to heal society’s open wounds. To this point, Ferrence quotes the poet Dean Young:

“Let us suppose that everyone in the world wakes up today and tries to write a poem. It is impossible to know what will happen next but certainly we may be assured that the world will not be made worse.”

Life and Death of the American Worker: The Immigrants Taking on America’s Largest Meatpacking Company by Alice Driver, Atria/One Signal Publishers

We uphold democratic values in our society, the idea that everything public and private, whether it’s the actions of the government or of major corporations, is shaped by the will of the people and serves the best interests of the majority. Yet, as we’ve seen across the books in this category, many deeply impactful decisions are made by a small group of people behind closed doors, ostensibly done in service of the “greater good” yet leaving most of us out of the decision-making process and coming up with results that many of us wouldn’t have agreed with had we known what was at stake. Nobody asked us, and yet not only are we beholden to the choices made by a small group of people, but we are also often made to believe that we were onboard and in agreement all along.

A book that lays this argument bare is Life and Death of the American Worker by Alice Driver. A native of rural Arkansas, she followed meatpackers at Tyson Foods from 2020 to 2024, documenting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon an industry already deeply fraught with dangerous labor practices.

“The four largest meatpacking companies in the United States control 54 percent of the poultry market, 70 percent of the pork market, and 85 percent of the beef market,” writes Driver. They have long used this financial might to lobby for more lenient industry oversight from state and federal government to bolster their bottom lines. Under these loosened regulations, the meatpacking industry has created a pipeline to employ members of vulnerable, easily exploitable communities, including undocumented immigrants, refugees, and nonviolent criminals working as an alternative to prison time, all of whom have few to no other options to picking up the backbreaking, low-wage jobs that no one else will.

Through interviews with frontline workers, Driver illustrates the everyday conditions of the typical American meatpacking plant and what its workers must face: long hours doing difficult physical work, inadequate personal safety gear, constant exposure to dangerous equipment and toxic chemicals, and severe time off and healthcare policies preventing workers from getting the rest and treatment they need. The surroundings are stomach-turning: “Plant floors are covered in a mixture of the oil used for frying, the mucus that clings to chicken, frozen bits of chicken, and blood,” Driver writes. The tasks are so repetitive that workers find themselves recreating the motions in their sleep and suffering nerve damage and chronic inflammation. Over a decade, an unchecked spate of ammonia leaks at various Tyson plants left hundreds of workers injured, leaving many with chronic respiratory illnesses. All of this became kindling for the impending wildfire of the pandemic. Driver writes:

With the arrival of COVID, I knew the choice the industry faced given my reporting experience in the meatpacking industry: follow the CDC’s social distancing recommendations and decrease COVID infection rates thus decreasing production, or continue on as though COVID did not exist. Decreasing production would mean less profit, something I knew the industry would never stand for, no matter whose lives hung in the balance.

As this mystery illness spread through the ranks, workers feared for their health and the safety of their families. Yet Driver notes, as the pandemic progressed, that banners went up at Tyson plants with declarations like “We are feeding the country,” and supervisors began pushing a narrative that, if Tyson workers stayed home, the nation’s food supply would suffer, and entire families might starve. In a recorded conversation, a Tyson supervisor declares to a frontline worker:

“The illness is going to kill some, perhaps a million and a half people, but if Tyson stops producing chicken, hundreds of millions will die.

Driver notes that “meatpacking plants were second only to prisons as the most significant sites of COVID infections in the US,” yet production carried on as usual. Despite their work being touted as necessary, even heroic, workers were largely left to fend for themselves. Said one frontline worker:

“I know that I shouldn’t be close to other workers. I try to be alone. My friends try to protect themselves because the company doesn’t care. Some wear double masks. Some go and eat outside alone. I don’t go to the lunchroom because it is very small. The company isn’t doing anything. They have left us to our own devices.”

Reading this book, I was gripped with a mix of helplessness and anger—nobody asked me what I thought, I found myself thinking over and over as I read on. I wouldn’t have agreed to this. Are we expected to wave away the harm and death of fellow human beings as the mere cost of doing business? Would any of us have really demanded that people turn around, head back to work, and risk their lives in exchange for a serving of chicken nuggets? Was there no other way we could have come together to survive?

Of all the injustices that Driver’s book reveals, perhaps the most insidious one is that most of us are being divided and pitted against each other by major corporations, often without even knowing it. Neither the consumer nor the employee’s interest is being served, and in fact, these faceless entities are banking on our division and isolation. Like kinetic energy, labor is never eliminated but transferred from one person to another. Whether it’s the pickers at an Amazon warehouse or the assembly line workers at a chicken plant, the products and services that seemingly make our lives more convenient and comfortable always come at the expense of someone else’s livelihood. How would our society transform if we chose not to look away but to recognize the full humanity in one another?

Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank by Justene Hill Edwards, W.W. Norton & Company

In a 2024 interview, former United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Marcia Fudge said about Black women: “We have for a very long time been the people who did the work, but never been asked to sit at the table.” In this case, she was referring to the Democratic Party, which has historically failed to recognize the efforts of Black women despite their ongoing support of its candidates. Exit polls following the 2024 presidential election showed that Black women and men almost entirely voted for Vice President Kamala Harris—92% and 77%, respectively, compared to 46% of White women and 38% of White men. And yet, here we are again, heading into the second term of a deeply divisive president whose proposed cabinet is noticeably lacking in racial diversity.

I bring all this up to highlight the fact that this nation has long engaged in a cycle of promises made and broken, chiefly at the expense of Black people. The 2024 presidential election is one of the most recent and visible examples, but the roots of this issue reach back centuries. In her new book, Savings and Trust, University of Virginia professor Justene Hill Edwards uncovers one of the first widespread betrayals of newly freed former slaves following the end of the Civil War. She tells the story of the Freedman’s Bank, depicting its hopeful beginnings through to its downfall at the hands of the bank’s white financiers. Though the story has been largely untold in the decades since the bank’s closure, its effects continue reverberating through society today.

At the end of the Civil War, Black soldiers in the Union Army faced a unique challenge: there was no place to store their savings. These soldiers were eager to build a financial foundation to support their families, but there was no straightforward entry into the banking system. In response, Union generals like Rufus Saxton established military savings banks to provide secure places for Black soldiers to keep their earnings. In its original iteration, the South Carolina Freedman’s Savings Bank would serve the mission of helping Black depositors build their wealth. “In contrast to commercial banks,” writes Hill Edwards, “which were institutions created to generate profits for shareholders, savings banks had a benevolent, as opposed to a moneymaking, mission.”

The Reconstruction era proved to be fraught with danger for Black Americans. “Instead of coming to terms with the reality of slavery’s end and Black people’s pursuit of full citizenship,” Hill Edwards writes, “[White Americans] used violence to combat the rising tide of African American political and economic uplift.” Yet, amid this uncertainty, there was hope for the future. Black women exercised unprecedented personal autonomy by patronizing the bank and opening in their own names. Hill Edwards notes:

[The] bank became a source of dignity for African Americans. It was an institution that represented their deservedness for the privileges that real inclusion, that is, citizenship, would bestow. African Americans who opened accounts took pride in their ability to work and save. They were also connecting their engagement in financial services to the goal of attaining political rights. Continuing to patronize the bank, African Americans believed, “is the way for our people to get equality of political rights.”

In March of 1866, a year after Congress chartered the Freedman’s Bank, the total deposits in the institution equaled $305,167 ($5.8 million in today’s dollars). Deposits would leap to $1,624,853.33 the following year ($33.2 million today) and eventually reach over $31 million ($773 million today) by March 1872, a breathtaking amount built up in less than a decade entirely by a Black community that many White people had believed incapable of managing their own finances.

It’s hard not to pause here and wonder what might have unfolded had African Americans in the post-Civil War era been able to lead the Freedman’s Bank and shape the institution to meet their needs and desires. Instead, the institution remained controlled by predominantly white (and often paternalistic) administrators. As the bank skyrocketed, administrators had to contend with increasing expenses as new branches quickly opened up. The bank generated meager returns from its limited investments as a nonprofit financial institution. To resolve this issue, Freedman’s Bank founder John Alvord proposed that the bank’s central office be moved from New York to Washington, DC.

The transition from New York to Washington inaugurated a new era in the bank’s priorities. No longer would the trustees and bank officials operate primarily by the bank’s philanthropic mission. The twin influences of big finance and high-level politics began to chip away at the bank’s benevolent foundation.

The savings bank began to operate more like a commercial bank, at first extending illegal loans drawn from the bank’s operational costs fund to members of its leadership team and then approving loans of high amounts and with lax regulations to individuals in their immediate networks. Borrowers were overwhelmingly White men despite making up only 8% of the bank’s account holders.

While the finance committee expanded the lending of millions of dollars to white men with connections to the trustees, including the trustees themselves, the Black people who were supplying the capital that the bank loaned to white borrowers, could not rely on the bank for lines of credit.

Soon, bank trustees began to pull funds from the bank’s deposits to pay for an opulent new headquarters and to invest in various stocks and bonds—all illegal financial pursuits. By 1873, the bank had become overleveraged—the bank’s available cash was insufficient to match what depositors had entrusted to the institution. Despite having created the dilemma, the bank’s trustees began to close their accounts and resign from their seats, leaving the matter behind for others to solve. By the time civil rights leader Frederick Douglass was appointed the bank’s president, supported by Black trustees Charles Purvis and John Mercer Langston, the institution was on the brink of collapse. Purvis and Langston hoped that his appointment would restore Black depositors’ faith in the institution, but on the other hand:

The white trustees’ decision to move forward with Douglass as bank president ensured that African Americans would bear the brunt of public criticism of the bank’s ultimate demise. The narrative would be that Black administrators mishandled the bank at the top and Black depositors were unable to handle the economic responsibility of freedom at the bottom.

The Freedman’s Bank ultimately collapsed in 1874, with Black depositors’ money tied up in outstanding loans made to White borrowers, most of whom opted not to repay what they had received. They had effectively plundered the coffers. The wealth that Black Americans had built was gone. “For freed people,” Hill Edwards writes, the failure of the Freedman’s Bank “represented the failure of the federal government, elected officials, white capitalists, and even African Americans with economic and political influence to protect their economic interests.” Hill Edwards recounts the story of Mary Susan Harris, an account holder who only recuperated 63% of the money in her account at the time of the bank’s failure and who passed away at the age of twenty-six. While her early death was not directly linked to the bank’s closure, Hill Edwards muses on the possibility that it could have been prevented had Harris had full access to her money.

The financial potential of depositors such as Mary Susan Harris are lost to history. We will never know the full scope of African Americans’ economic possibilities had the bank succeeded and not succumbed to both the unpredictability of the global capital market and the greed of white capitalists.

Today, 150 years after the collapse of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, the financial disparities between Black and White households are stark. Hill Edwards writes:

Based on the Survey of Consumer Finances, the median wealth of Black families in 2022 was $44,900, while the median wealth of white families was $285,000. This meant that the typical Black family held about 15 percent of the wealth of the typical white family.

In 1901, regarding the bank’s collapse, writer W.E.B. DuBois declared, “Not even ten additional years of slavery could have done as much to throttle the thrift of the freedmen as the mismanagement and bankruptcy of the savings bank chartered by the nation for their especial aid.” Indeed, the story of the Freedman’s Bank is a clear example of systemic racism—systems of finance and government waged what Hill Edwards calls “the financial violence of theft” upon a population still recovering from the horror of slavery. The effects have not gone away. It’s impossible to deny that we still live in a society that gives false hope to Black Americans, exploits their efforts, and ultimately breaks their trust.

This is a somber note to end on, I know. Maybe it feels like there’s nothing to do but wallow in despair, to accept that people are inherently evil, and to resign ourselves to the idea that we’re all doomed. Or maybe we decide to do something about it all.

All five books in this category illuminate forgotten aspects of our nation’s history and reveal the invisible forces that have shaped our lives, not with an intent to frighten us but to help us understand the problems we can solve. This feeling of dread that looms over us in this present day can, indeed, be faced, and we can still change our world for the better.

John Mercer Langston, one of the few Black trustees of the Freedman’s Bank, was the great-uncle of Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. It seems fitting to let Hughes have the final word here with an excerpt from his poem, “Let America Be America Again.”

O, let America be America again—

The land that never has been yet—

And yet must be—the land where every man is free.

The land that’s mine—the poor man’s, Indian’s, Negro’s, ME—

Who made America,

Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain,

Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain,

Must bring back our mighty dream again.Sure, call me any ugly name you choose—

The steel of freedom does not stain.

From those who live like leeches on the people’s lives,

We must take back our land again,

America!O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death,

The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies,

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.

The mountains and the endless plain—

All, all the stretch of these great green states—

And make America again!

...

Porchlight will announce the eight winners of the 2024 Porchlight Business Book Awards–one from each category–at the end of January. Be one of the first to know by subscribing to our weekly newsletter.

View past issues here.

By joining our mailing list you consent to having your data processed as shown in our privacy policy.