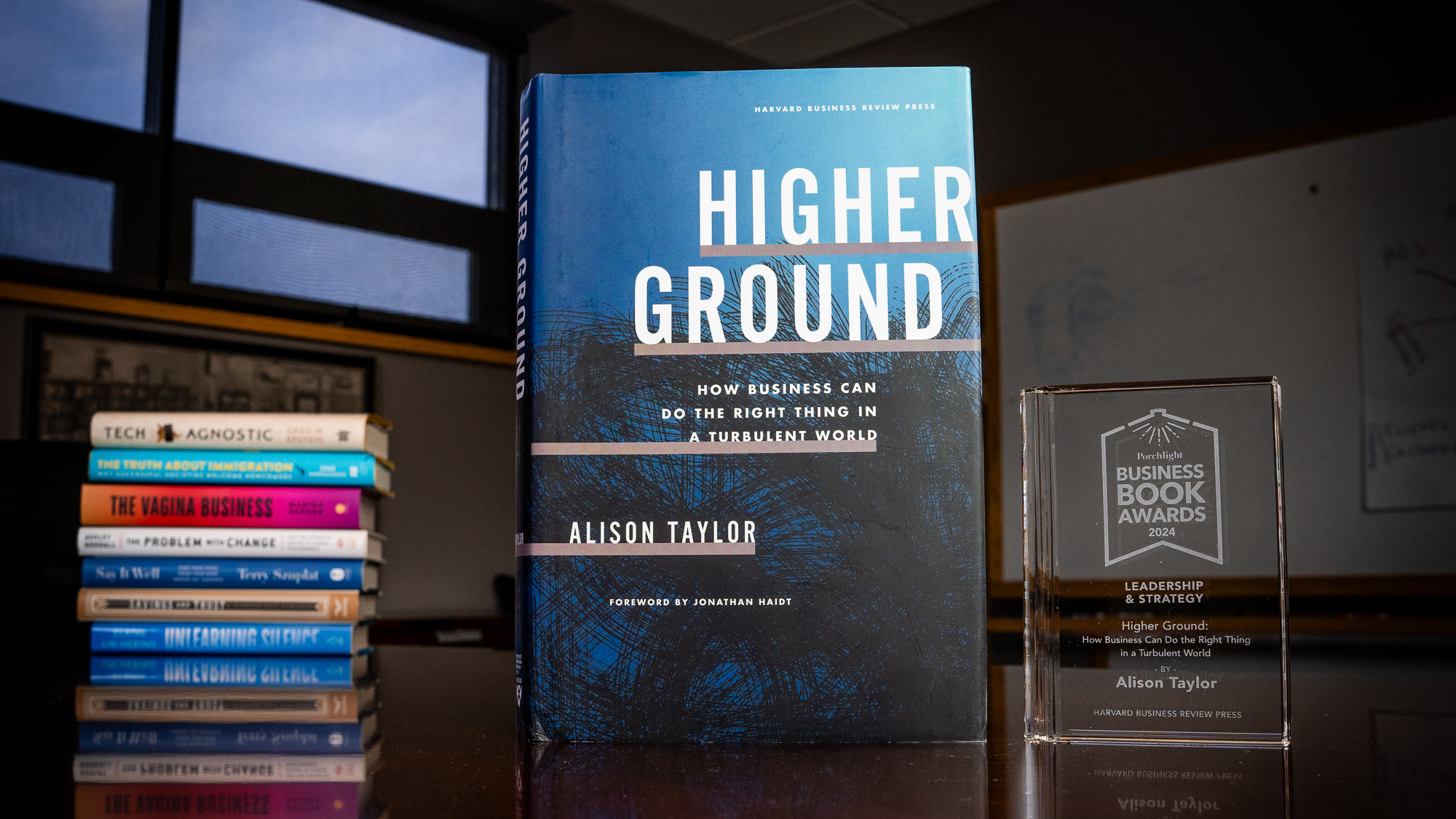

Higher Ground | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Leadership and Strategy Book of the Year

Reviewing Alison Taylor's Higher Ground in her post about 2024's best leadership and strategy books, Porchlight's Managing Director Sally Haldorson wrote:

Higher Ground reminds us (to liberally and perhaps poorly adapt John Donne’s famous lines) that ‘no company is an island, entire of itself, every company is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.’ And because of this, leaders must understand that the decisions made for the good of the company must also be made for the good of the people and of broader society.

Of course, in our hyperpartisan times, opinions on what is good for people and society differ greatly, and it seems businesses can no longer stay completely free from those politics—however we may wish otherwise. How did it become this way and what can business leaders do? In the excerpt below, Alison Taylor starts to answer those questions.

How Business Became Political

Companies everywhere now find themselves caught between the Scylla of political risk and the Charybdis of social license to operate.1 Western enterprises encountered unprecedented pressure to close their operations in Russia when it invaded Ukraine in March 2022. As prominent Yale professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld was fashioning a spreadsheet to help the media track which companies were in and which were out, CEOs with operations there had to decide almost instantly whether to keep paying employees, evacuate Russian nationals, sell the assets, or try to stay put.2 (Western companies perceived to have handled the issue well soon found themselves facing questions about their operations in such authoritarian countries with poor human rights records as China and Saudi Arabia.3)

Far from Moscow, HSBC struggled to balance support for racial justice in the United States with its tacit acceptance of crackdowns in Hong Kong.4 Telecommunications company Telenor sold its Myanmar operations to a Lebanese investment firm after the 2021 coup made it impossible to meet human rights commitments, only to be criticized afresh over the manner of its withdrawal.5 Multinational brands face demands from Western consumers to address poverty, pollution, and human rights abuses in their supply chains. Those consumers still want the stuff they ordered, right now.

In a sharply polarized US environment, corporations encounter loaded dilemmas at every turn. A 2022 decision by the US Supreme Court terminating any national claim to abortion rights left companies wrangling with distressed staff, state-level medical restrictions, and threats of political retaliation should they take steps to help employees obtain certain procedures.6 (While assisting access to abortion might strike overseas observers as a limited business priority, most US companies provide core healthcare benefits to employees, and their specific offerings are important to employees and potential hires.) Similarly, it was left to many businesses during the Covid-19 pandemic peaks to decide whether to enforce requirements for masks and vaccines. And disparate gun regulations in many US states force companies to choose whether to allow firearms in their offices or stores.

These are certainly matters of geopolitical risk in a multipolar world, but this lens is too narrow. As University of Chicago professor Luigi Zingales pithily put it, “We now have the politicization of the corporate world because we have corporatization of the political world.”7 Globally, the public sees business as more responsive to its dictates than nation states and expects it to play a more active role in a world reeling from political and regulatory failures. Some companies wind up implicated in these problems by virtue of previous lobbying, tax avoidance, and corruption. Others are simply caught in the tailwinds of shifting expectations. Anxious customers, shareholders, and employees have embraced activism. Corporations are their target.

I first experienced this transformation in my own work when communities situated around mining and infrastructure projects began reframing longstanding complaints about water pollution and relocation as human rights violations, and then connecting them to a wider struggle against corporate irresponsibility. Soon I was being cornered at parties in New York by people eager to discuss how offshore finance and money laundering were pushing up property prices.

What made ordinary people so angry? To start with, the 2008 financial crisis was ameliorated by the injection of vast public subsidies into private companies, swiftly followed by severe and continued austerity in public spending. The disruption’s aftermath undermined the sense that bankers and policy makers could be trusted to act like the adults in the room. No meaningful retribution met those perceived to have caused the crash, and scant reform was applied to the financial system.

In 2011, Occupy Wall Street, the Indignados of Spain, and the Arab Spring flourished as early examples of intersecting sociopolitical frustration.8 In 2014, protesters in Hong Kong and the United States commonly used the same hands-up gesture to signify opposition to repressive police tactics.9 In 2019, as Catalan militants in Barcelona were waving the flag of Hong Kong, and Lebanese protesters were hoisting anti-Brexit placards, Chile’s government released a statement blaming protests on international influences and media—including Korean pop music.10

Protests abated during Covid-19 lockdowns, but frustration kept mounting. Rapid urbanization in many developing countries badly strained government services, even as it begat communities of underemployed youths with little to do but organize around grievances. Environmental and climate stresses became key stimulants for protest in many nations, with schoolchildren at the forefront. At the same time, demonstrations took to erupting over governmental environmental initiatives that threaten to raise fuel costs and reduce jobs in mining and fossil fuels. Evidence suggests that only a minority of the world’s population trusts governments, many of which tend to respond to crises by vacillating or indulging authoritarian impulses.11

When critical stakeholders push companies to take on more overt social and political roles, it’s tempting to meet this emerging demand. Many CEOs now pitch themselves as activists and their organizations as agents of social change. A 2021 global survey by GlobeScan and Oxford University found that 75 percent of companies now have “some appetite” or a “strong appetite” for corporate activism.12

CEO activism emerged decisively in the United States during the early stages of Donald Trump’s presidency and, by 2018, was being described as the “new normal” by the New York Times.13 The proximate cause was the Trump administration’s zest for drawing business leaders into chaotic policy conflicts that might inflame the domestic culture wars. But Trump’s divisive leadership was merely a catalyst—the most visible sign that old assumptions are no longer reliable or even relevant.

Big business had carefully avoided polarized messaging for decades. The status quo was to avoid controversy and maintain alliances across the political spectrum. As that neutral middle ground shrank, CEOs and their teams discovered that well-timed ideological appeals could galvanize customers and workers. When the Trump administration withdrew from the Paris Agreement on climate change, scores of businesses responded: “We Are Still In.”14 Nike’s sponsorship of quarterback Colin Kaepernick and his football protests drove its stock price to an all-time high, while Chick-fil-A profitably doubled down on its conservative agenda.15 When Kenneth Frazier of Merck became the first CEO to resign from Trump’s manufacturing council after violent right-wing protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, he was widely applauded.16 My students no longer regard political neutrality as a realistic option for companies; many are surprised to hear it was once customary.

Those ideological appeals had unfortunate second-order consequences for both internal culture and societal divisions. CEOs at Coinbase and Basecamp moved to ban internal debate over politics in order to return to their companies’ core missions; their employees quit in droves amid a wave of critical press reports.17 Then came more organized backlash. In the United States, Republican politicians denounced “woke” branding efforts by which corporations sought to appeal to younger workers and consumers. Meanwhile, Democrats continued urging companies to speak up on controversial questions, and investors to divest from oil and gas.18 When Disney’s CEO infuriated both employees and politicians by vacillating about LGBTQ rights in Florida, corporate leaders started to worry about getting “Disneyed.” He was soon replaced, though the controversy was just getting started.19

Old assumptions and accepted wisdom no longer offer reliable solutions. Indeed, the corporate tendency to favor siloed, piecemeal responses frequently worsens matters. Are climate change and racial justice political issues? Or are they deeply personal? That depends on whom you ask.

It’s very hard to draw back from taking stands once you’re begun. Proclamations that core values are as important and fundamental as profit shifted the Overton window (the range of ideas and policies the public will accept at a given moment) and opened the corporate arena to negotiation, debate, and pressures from all quarters. Taking a stand on any issue now invites suspicion of hypocrisy and scrutiny as to whether your company’s actions—and political spending—match your rhetoric.20 Doing the right thing is far more demanding than it looks.

So now that everyone is yelling at you, how do you decide whom to listen to?

Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review Press. Excerpted from Higher Ground: How Business Can Do the Right Thing in a Turbulent World by Alison Taylor. Copyright 2024 by Alison Taylor. All rights reserved.

Endnotes:

1. EncyclopediaBritannica.com, accessed June 7, 2023, https://www.britannica.com /topic/Scylla-and-Charybdis.

2. Robb Mandelbaum, “The Viral List That Turned a Yale Professor into an Enemy of the Russian State,” Bloomberg, December 6, 2022; Elisabeth Braw, “Russia’s Clueless New Oligarchs,” Foreign Policy (blog), September 29, 2022.

3. Elisabeth Braw, “It’s Just Not Easy Saying Goodbye to China and Russia,” Politico, March 15, 2023.

4. Primrose Riordan, “Political Pressure Weighs on HSBC over Hong Kong Activists,” Financial Times, January 5, 2021.

5. Chloe Cornish and John Reed, “Myanmar Rights Groups Complain to OECD over Telenor Sale,” Financial Times, July 27, 2021.

6. Nicole Goodkind, “Forget Disney and Florida, Companies Won’t Be Able to Stay Silent on Abortion,” CNN, May 4, 2022.

7. James Mackintosh, “What I Learned about ‘Woke Capital’ and Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago,” Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2023. This comment was used in a class lecture attended by Mackintosh, confirmed directly with Professor Zingales.

8. “Ten Years after Spain’s Indignados Protests,” Economist, accessed June 5, 2023.

9. Lily Kuo and Quartz, “Why Hong Kong’s Protesters Have Their Hands Up,” Atlantic, September 29, 2014.

10. Melissa Lemieux, “Chilean Government Blames K- Pop for Recent Protests,” Newsweek, December 24, 2019.

11. Esteban Ortiz- Ospina and Max Roser, “Trust,” Our World in Data, July 22, 2016.

12. Robin Miller, “ESG Performance Tops List of Corporate Affairs Risk Priorities Globally for Organisations,” GlobeScan, July 15, 2021.

13. David Gelles, “C.E.O. Activism Has Become the New Normal,” New York Times, July 25, 2018.

14. “We Are Still In,” accessed June 5, 2023.

15. Jia Wertz, “Taking Risks Can Benefit Your Brand—Nike’s Kaepernick Campaign Is a Perfect Example,” Forbes, September 30, 2018; Rachel Sugar, “Chick- Fil- A’s Controversial Politics Haven’t Stopped It from Becoming One of the Biggest Fast-Food Chains in America,” Vox, December 20, 2018.

16. Aaron K. Chatterji and Michael W. Toffel, “The New CEO Activists,” Harvard Business Review, January 1, 2018.

17. See Sarah Kessler, “A Third of Basecamp’s Workers Resign after a Ban on Talking Politics,” New York Times, April 30, 2021; Kim Lyons, “Basecamp Implodes as Employees Flee Company, Including Senior Staff,” Verge, April 30, 2021; and Abigail Johnson Hess, “Companies Like Basecamp and Coinbase Have Tried to Ban Political Discussions at Work—Experts Say It’s Not That Simple,” CNBC, May 5, 2021.

18. Robert Eccles and Eli Lehrer, “It’s Time to Call a Truce in the Red State/Blue State Culture War,” Harvard Corporate Governance (blog), May 29, 2023.

19. Daniel Arkin, “Why Disney Brought Back Bob Iger and Booted His Handpicked Replacement,” NBC News, November 21, 2022.

20. “Home—Center for Political Accountability,” accessed June 5, 2023.