Inside the 2019 Longlist: Current Events & Public Affairs

We made room in our annual business book awards for authors covering current events and public affairs in 2016. We did so because an understanding of the state of those events and affairs is so crucial to business, and because business has such an outsized influence on them. Public policy is, of course, foundational to how businesses operate and how economic developments unfold. And to make that policy and understand its effects, we must have a baseline of facts we can all generally agree upon, a shared vision of where we want to go and what we want to build, and what we need to invest in to build it.

Just this morning, the recent trajectory of current events and public affairs led the House of Representatives to announce two articles of impeachment against the sitting President of the United States. That is an historic and monumental announcement, and one we should all keep a close eye on—hopefully going beyond the headlines and chyrons crossing our television screens. But with partisanship and economic inequality at levels unseen since the Gilded Age, fact-based and clear-eyed examinations of current events too often get drowned out in the mudslinging, disinformation, and conspiracy theory that goes unchecked in our always-on information age. As Lewis Lapham wrote in his introduction to the latest issue of Lapham’s Quarterly:

[T]he incessant bombardment of new and newer news blows away the chance of knowing what most or any of it means, and darkens the approach to the value of our minds. The sound and fury of an instantly shattering Now carries away all thought of what happened yesterday, last week, two hundred or two thousand years ago.

In sorting fact from fiction, it is imperative we remember the events and individuals that shaped the broader contours of our present moment. So, regardless of how he leaves office, I find it instructive to remember that the President came to office based largely on what he said we ought to build: a wall. Using the specter of immigration to stoke fear and division for political gain is not a new development in the United States—read Erika Lee’s recent book, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States for a thorough history—but it isn’t a solution to the real challenges we face as a nation, and increasingly as a species.

What can help is investigating facts, establishing a shared reality, and believing that the truth still matters. That is a conversation worth having, and one that each of the following books helps foster.

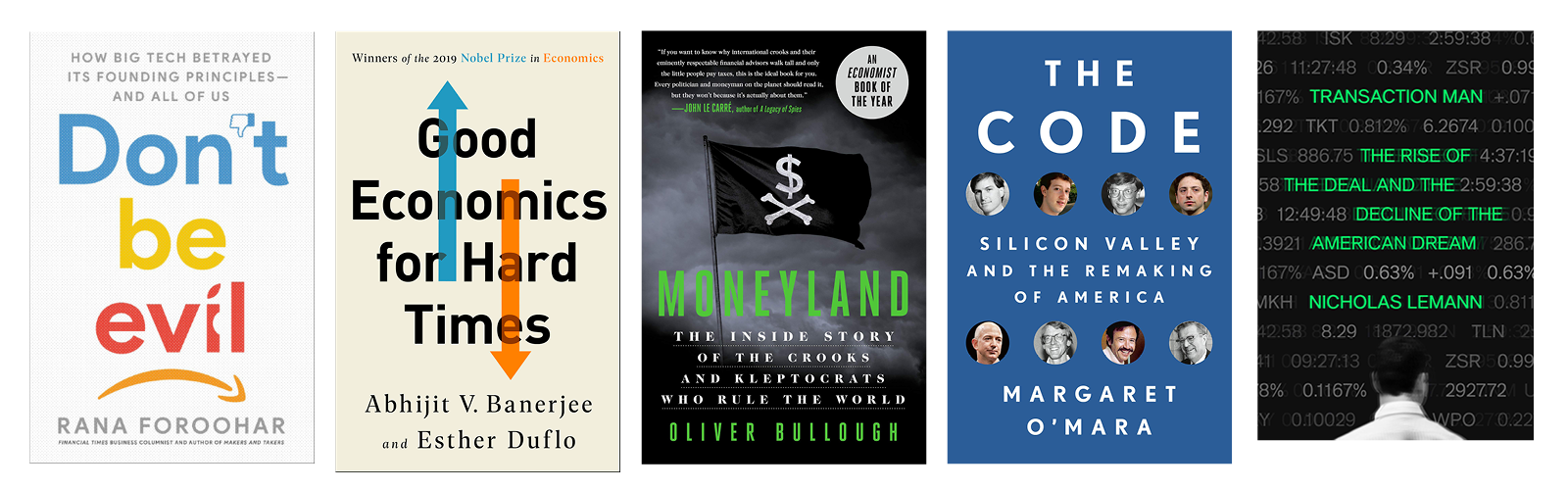

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America by Margaret O'Mara, Penguin Press

University of Washington Professor Margaret O’Mara masterfully unfolds the history of Silicon Valley in the pages of The Code, showing how its rise intersected with both big government investment and free-market innovation, how intertwined the “new economy” is with the old, and how geopolitical forces and a small group of interconnected individuals helped shape it all.

Through that story, we gain a greater understanding of how the investment made by the government in advanced electronics and information technology during the Cold War competition between “American capitalist democracy and Soviet communism” created the conditions for the unprecedented growth of “a pleasant and sleepy corner of Northern California” into an economic juggernaut that has given us:

Three billion smartphones. Two billion social media users. Two trillion-dollar companies. San Francisco’s tallest skyscraper, Seattle’s biggest employer, the four most expensive corporate campuses on the planet. The richest people in the history of humanity.

At a time that we’re debating tuition-free higher education, it is instructive to remember that Stanford, the university at the center of Silicon Valley, began as a tuition-free educational institution founded by a railroad tycoon. At a time when the tech industry fights regulation, it is enlightening to learn that the environmental regulations signed into law by Richard Nixon actually created a hundred million dollar industry in the Valley for computer systems that analyzed environmental data. Such historical perspective is abundant in The Code, but the greatest achievement is how it helps us understand the present moment. In detailing how government policy and investment combined with entrepreneurial innovation can shape not only a region, but create an entire industry that reshapes the world and alters human civilization, the book is a great reminder that we can accomplish big things—and do things differently. The next book on our list helps us understand why we should, in fact, do things differently.

Don’t Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles—and All of Us by Rana Foroohar, Currency

Silicon Valley has always painted its intentions in a utopian hue: to connect humanity, democratize access to information, to disrupt an old order of entrenched power and usher in a new, more equitable and innovative age. But, as global business columnist and associate editor at the Financial Times Rana Foroohar lays out in her new book, “the supposedly decentralized Internet economy has spawned a handful of ruthless oligopolies that have begun to use their power to undermine start-up growth, job creation, and labor markets.”

In a final twist of the knife, the disruption to labor markets and local economies that these firms (and too much business literature) have so lauded over the last decade has created an even greater need for government investment to help lift up those left behind, investment that is dependent on tax revenue, tax revenue that Big Tech firms now actively avoid providing—the kind of investment, again, that the industry’s very roots were watered in—by moving their intangible assets to countries in which they won’t be taxed.

It is a development that mirrors the deregulation of financial institutions that led to the Great Recession—documented so well in Foroohar’s previous book, Makers and Takers—also sold as an opportunity for innovation and a new economy that ended in a similarly increased concentration of wealth and risk, political clout and privilege, and a lack of any real accountability. Big Tech is also introducing a similar systemic finaincial risk by making risky investments in corporate debt, chasing ever greater returns, essentially acting like a bank while be free of the regulations and transparency that guide such institutions.

And, of course, there are issues of personal privacy, internet addiction, monopoly power, the undermining of innovation and competitive free markets, and the survival of our very democracy swirling around it all. But Foroohar doesn’t just point out the many transgressions coming out of Silicon Valley and the challenges they pose to us as a society, she also offers solutions, from a “national commission on the future of data and digital technology” to a digital New Deal to ensure employment and “remake the real economy for the digital age.”

Moneyland: The Inside Story of the Crooks and Kleptocrats Who Rule the World by Oliver Bullough, St. Martin’s Press

The financial chicanery described in Oliver Bulluogh’s book is of a piece, but far more nefarious than that described Foroohar's Don't Be Evil.

Moneyland is another angle to view the deterioration of the postwar economic order and the rules established at Bretton Woods to govern it, which while far from perfect, at least had the benefit of some semblance of stability. Rather than repair it, that order was upended at first, in Bullough’s telling, by a “EuroBond” market established in 1960s England that made it easier for wealthy individuals to “offshore” their money. Once that pattern was established, it propagated itself.

Today, the island of Nevis has more registered corporate entities based on it than human beings. St. Kitts pioneered the selling of passports that wealthy individuals use to skirt their own nation’s laws. Some nations are now offering diplomatic posts, along with the diplomatic passport and immunity it confers to the super rich, to get their share of this “investment.” It has created an essentially lawless situation in which national security is undermined by dark money with connections to dictators, oligarchs, and even terrorism that is filtered into the financial institutions of the West—where it is seen as safe (in large part, from prying investigative eyes) and is easily accessible.

We need journalists like Oliver Bullough to uncover such corruption and kleptocracy, to help provide the facts that underpin fact-based investigations and dialogue about such transgressions. So it is alarming that Bullough has had an article he worked on and sourced for over two years (about an oligarch who had been able to avoid the 2014 sanctions that resulted from Russian’s annexation of Crimea) that has never been read by the public, and a documentary film (about repairing Ukraine after the systematic looting that took place there by Viktor Yanukovych) that has never been shown—both killed due to the threat of legal action in under the UK's strict libel laws. All of which makes it more important to promote this investigative powerhouse of a book.

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream by Nicholas Lemann, Farrar, Straus and Giroux

As evidenced in the book’s subtitle, Nicholas Lemann’s book bemoans the decline of the American Dream. But to many, on both the left and the right, that dream was a nightmare. In the liberal critique, the industrial corporation that once dominated American work and life was seen as a breeding ground for conformity and the birth to the “Organization Man.” The conservative criticism was that the industrial corporation had become too concerned with social forces rather than market forces, and that their only focus should be on maximizing profit, not on the wellbeing of individuals or society. As the social revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s played out—largely in response to the liberal critique of the system—it was that second criticism, largely emanating from the University of Chicago, that would change the fundamental structure of our economy.

Lemann’s task in the book is to “lay out the history of our move from an institution-oriented to a transaction-oriented society.” He does so through the stories of two men: Adolf Berle, who witnessed and warned against the rise of the modern industrial corporation while working on Wall Street in the 1920s, became an economic advisor to FDR and one of the architects of the New Deal, and who eventually championed the role of industrial corporations in creating widely-shared prosperity; and Michael C. Jensen, a graduate of the University of Chicago’s economics department who was a prominent early booster of the idea of market efficiency that helped provide the intellectual basis for the shift in the balance of power from state regulation and control of the economy to unfettered financial markets. (A third shift, toward a network-oriented society, is examined through the person of Reid Hoffman at the end of the book.)

Transaction Man is a history of the big ideas that have shaped the last century of the American economy, brought home with a story about their effect on the individual communities that make up America. It is about the decline of a New Deal that worked for many, but not all, and resurrecting a largely abandoned political philosophy that helped create social progress within the communities that comprise an ever shifting society and body politic: pluralism.

Good Economics for Hard Times by Abhijit V. Banerjee & Esther Duflo, PublicAffairs

Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo are a rare breed: academic economists that can write for a popular audience. They begin their new book focusing on immigration and trade, two topics that have geopolitical implications and spawn intense political debate and acrimony across the globe, but that most economists have reached a general consensus on: that “immigration is good,” and “free trade is better.” (There is, of course, a lot more nuance and depth to their case—about 100 pages of it.)

They go on to tackle even more existential economic issues: “the future of growth, the causes of inequality, the challenges of climate change.” One of the larger concerns in regards to the future of growth ties in with Rana Foroohar’s examination of Big Tech’s disruption of job markets, which Banerhee and Duflo help us understand as the continuation of an ongoing development:

Tech moguls are getting desperate to find ideas to solve the problems their technologies might cause. But we don’t need to contemplate the future in order to get a sense of what happens when economic growth leaves behind a majority of a country’s citizens. This has already happened—in the United States since 1980.

Their book is, like the others on this list, a way to cut through the noise of the daily news, to step outside it and examine the broader ground we stand on and understand the terrain both behind and in front of us. It is only through gaining such a bearing that we can make sound judgment and policy—policy, for instance, in regards to how to structure tax cuts:

Once again, this underscores the urgent need to set ideology aside and advocate for the things most economists agree on, based on recent research. In a policy world that has mostly abandoned reason, if we do not intervene we risk becoming irrelevant, so let’s be clear. Tax cuts for the wealthy do not produce economic growth.

On issues ranging from immigration and trade to the rise of automation, inequality, and nationalism worldwide, the simple fact is that “too many politicians do not try to hide their contempt for the poor and disadvantaged,” and they use that contempt as a way to divide us rather than engage in a debate on the facts before us. It is a debate, the authors suggest, that we must all engage in, that must transcend allegiance to identity politics and put human dignity back at the center of our economic priorities and policy debate, because even these economists believe that “Economics is too important to be left to economists.” Too important, one could argue, to be left to any one president.