The 2023 Porchlight Business Book Awards | Management & Workplace Culture

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Or maybe it was lunch. Either way, there is no evidence the famous quote was ever uttered by Peter Drucker. Credited apocryphally to the father of modern management, the imagined quote belies the need for both. The fact is, the two are inextricably linked. Inasmuch as pursuing a new strategy is about making choices that change the focus and trajectory of an organization, strategy is inherently about culture—specifically culture change.

Our Managing Director Sally Haldorson has already covered the best Leadership & Strategy books of 2023, but I mention the connection between strategy and culture because it is imperative that we do, in fact, change. A strange thing has happened in our current incarnation of capitalism. The metrics that have become proxies for assessing our quality of life have come to damage that very quality of life. Our laser focus on economic growth has hindered growth in other areas, and even prohibited it. The climate crisis, the unconscionable amount of economic inequality permitted and allowed to persist in our society, and many other ills are linked to how we manage things, to how we manage business, what should be considered important to a business, and who it should benefit. The focus on constant financial growth above all else has created a grind culture that isn’t good for our mental health or—ultimately—our bottom lines. Under that pressure, our momentum eventually grinds to a halt.

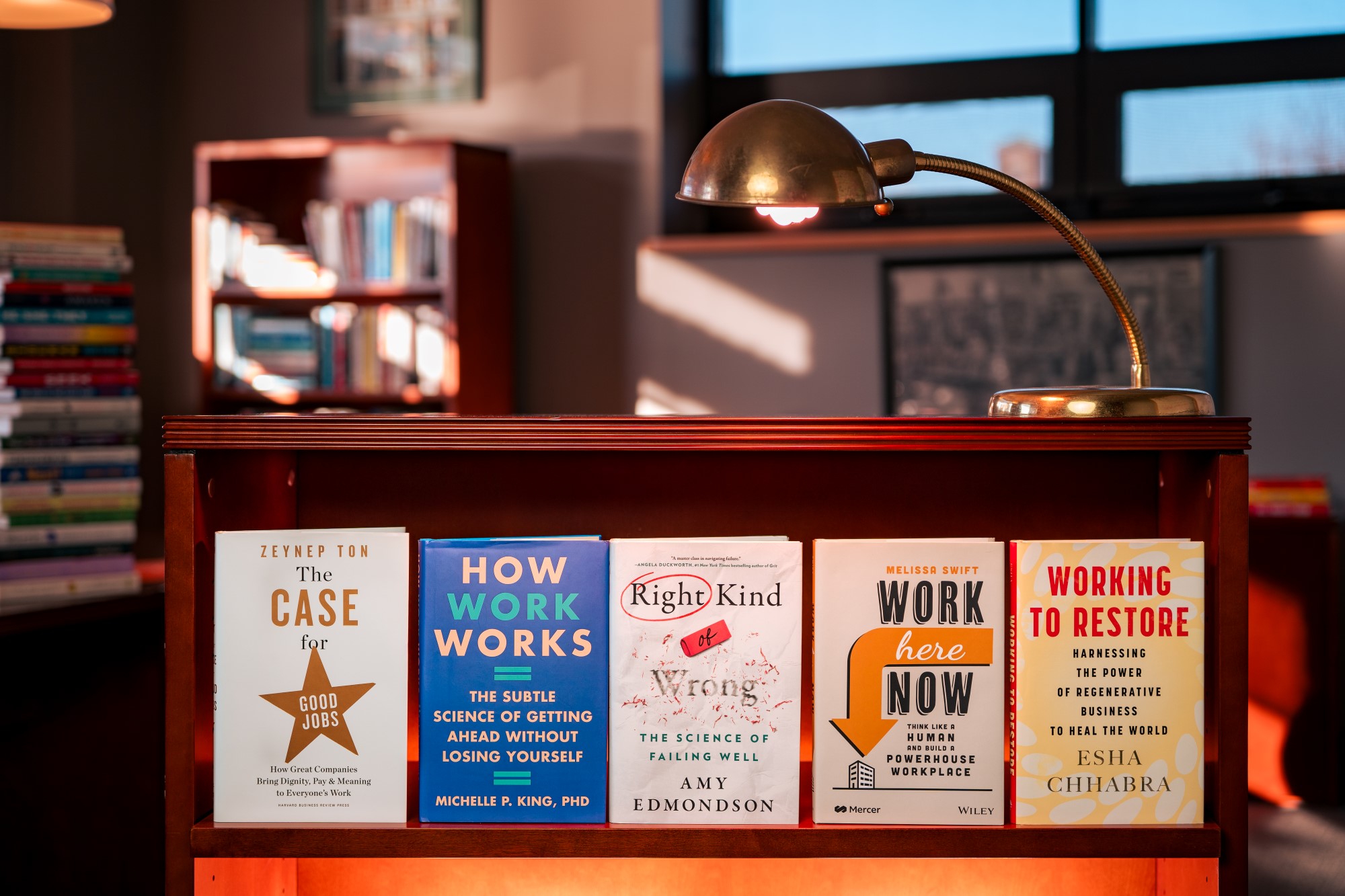

We need to counter the idea that “what is good for business” is a purely financial consideration and start considering the people and planet that form the foundation of our, and all, economies. We must remember that solving problems and serving people is the surest way to building and managing a good and profitable business. Success should not be defined by who is able to extract and capture the most resources and wealth, but how well we build a way of doing business and building organizations that will continue to increase the quality of life—rather than undermine it—for the generations to come. To do that, we need to create good jobs, strong cultures, humane processes, and healthy workplaces to carry out the work that needs to be done. These five books all offer examples and instruction for how to do that work.

The Case for Good Jobs: How Great Companies Bring Dignity, Pay, and Meaning to Everyone's Work by Zeynep Ton, Harvard Business Review Press

Even before the pandemic, there was a burnout epidemic across American business. Worker engagement numbers were, and remain, abysmal. People felt overworked and underpaid. The (admittedly overhyped) phenomena of the great resignation and quiet quitting followed. But, as Zeynep Ton shows in The Case for Good Jobs, “there is an excellent alternative to that kind of anxiety and exhaustion,” one that even low-cost competitors can take up.

Companies like Spanish supermarket chain Mercadona, Costco, and Trader Joe’s have proven that providing a living wage and opportunities for growth to their workforce literally pays dividends—even as they compete on cost. They experience less turnover and attrition and provide greater service to their customers than their competitors, exemplifying what Ton calls the “good jobs system.” And it is important to consider it as a system.

In Chapter 5, Ton turns to W. Edwards Deming, considered the founder of the Total Quality Management approach eventually adopted by Mercadona in the early nineties, to encourage us to “look at the system in which the workers operate—not the workers themselves—to understand the root cause of problems.” One of the root causes of the problems in our society, as we learned during the pandemic, is that our most essential workers are often underpaid and overworked. The answer, for both the workers themselves and more broadly for a functioning society, is not for them to move out of these essential jobs, but to make them better jobs. As Ton writes:

“Upskilling” workers to better jobs sounds good on paper but won’t solve the problem, in part because most job growth is expected to come in low-wage sectors. Caregiving jobs are the fastest-growing occupation and are notoriously bad jobs. But, in fact, it isn’t necessary that caregivers, waitresses, and so on upskill to become nurses and computer programmers. The jobs they have right now—in retail, restaurants, call centers, and senior living facilities—are important and can be good jobs with living wages, decent benefits, and opportunities for growth and success.

We don’t need to fix the people doing this important work; we need to fix the system that undervalues them and the essential work they do. By the end of the book, Ton suggests:

It might have occurred to you that this book advocating some pretty big changes in corporate behavior is really about old-school principles of good management.

I wrote in my introduction to this piece that we need to change, but thanks to everyone from Drucker to Demings to Ton, and the other four authors in this category, we know there is precedence for, and are principles for, much of the change we need to see. Surprisingly, and perhaps reassuringly, a lot of this work is about a restoration of “old-school principles” and returning to what we know works and work.

Which brings us to…

READ AN EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK HERE.

How Work Works: The Subtle Science of Getting Ahead Without Losing Yourself by Michelle P. King, PhD, Harper Business

Michelle P. King’s book would be beneficial in any era, but it is especially important in our own. The responsibility for managing a company and developing the culture within it is becoming the responsibility of everyone, regardless of where they reside physically or on the organizational chart. As remote and hybrid work become more prevalent, and organizations move to flatten hierarchy to “ensure faster decision-making and enable on-the-job learning and collaborative problem-solving,” we all need to be able to manage the greater ambiguity, new ways of working, and the informal side of work. How Work Works helps us do that. It is a book about being able to “read the air” in an organization, about how work gets done rather than what work gets done.

It is not a book for managers to learn how to manage employees (though it will help with that), but a book for all of us about how we manage our careers. In that sense, it could have ended up in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category, but because a better understanding of the interpersonal and informal elements of work makes us better coworkers and improves organizations, it is very much a workplace culture book. In teaching us to navigate culture, it helps us improve the culture. It also helps us improve our lives:

Your ability to find meaning at work increases your ability to find meaning in the rest of your life.

You don’t need to be defined by your work or give into the grind to leave a place better than you found it. If you can learn to read the air, you can help work be less of a grind for yourself and others and define the work you do instead of the other way around. Throughout, King also widens the scope to explode “the myth that capitalism is a zero-sum game,” that “[t]o win it, we need to make money at all costs.” She reminds us that:

What’s bad for people and the planet is ultimately bad for profits.

Most importantly, King reminds us that “we are our workplaces,” and that within the organization we are “connected by our shared contributions.” You are, of course, more than just your workplace, but:

Managing your career is how you manage your work experience and, ultimately, what you leave behind.

The more people who find this book, the better. I believe it will benefit everyone who reads it and every organization it finds its way into.

READ AN EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK HERE.

Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well by Amy Edmondson, Atria Books

Our Managing Director Sally Haldorson wrote about the incomparable Billie Jean King in her examination of this year’s best leadership books. In The Right Kind of Wrong, Amy Edmondson calls on King for the opening quote of Chapter 8. “For me,” King said, “losing a tennis match isn’t failure. It’s research.” What a great quote. It sums up nicely the foundational idea of the entire book, that failing is only a true failure when you neglect to learn anything from it.

Edmondson has become most widely known up until this point for her work on psychological safety. The term may sound a bit squishy and soft to the uninitiated, but is rooted in in the rigor of Edmonson’s engineering background and the wealth of her academic research and expertise. Like Move Fast and Fix Things in the Leadership & Strategy category, Right Kind of Wrong starts with an understanding that we are all fallible human beings working in imperfect systems. What The Right Kind of Wrong adds is that failing well is a science we can master, and a system we can implement. At its best, failure is a process of both personal and collective discovery that leads to success:

Discovery stories don’t end with failure; failures are stepping stones on the way to success. … These kinds of informative, but still undesired, failures are the right kind of wrong.

So, while failure may not be welcome, or desirable, it can be instructive if we work in an environment without an excessive fear of failure, where self-protectionism isn’t a widespread practice, where experimentation and iteration are encouraged, and failures are shared and examined instead of seen as personal mistakes that are prosecuted by bosses.

Edmondson reflects on the horrific crashes of two Boeing MAX 737s in 2018 to illustrate how an organizational culture that refuses to engage with internal criticism, that doesn’t offer employees the kind of psychological safety they need to speak up and point out a risk, can lead to a complex failure.

What each of us must take to heart is that uncertainty and interdependence in almost every aspect of our lives today means that complex failure is on the rise. ... Seeing the world around you for its complex-failure propensity sets you up well to navigate the uncertain future ahead.

Edmondson also blends in stories from people’s personal lives, ranging from how a noted futurist’s examination of a disastrous date set up by an online dating site ultimately led to finding her future spouse, to how her own kids’ growth mindset led them to become better skiers when they began asking her for more instruction on what they were doing wrong rather than accepting her telling them that they were doing great. Stories like that serve as reminders that we must overcome our personal aversion to failure and put ourselves in novel situations we might not be immediately comfortable in, to try things we might not (yet) be good at.

We can’t shield ourselves from disappointments and failures. But we can learn healthy, productive responses to setbacks and accomplishments alike.

Not only can we, but so can organizations.

READ AN EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK HERE.

Work Here Now: Think Like a Human and Build a Powerhouse Workplace by Melissa Swift, Wiley

An old-school, actionable business book chockfull of bullet points and “What to Do” advice, Melissa Swift’s Work Here Now also brings a decidedly fresh voice and perspective to the genre. Yes, Swift includes ninety bullet pointed strategies for improving work—a truly comprehensive series of real-world updates we can implement in the workplace. But, the book is also legitimately funny, which counterbalances her frank appraisal of today’s workplaces. Swift doesn’t shy away from the problems we face at work, beginning the book with the most fundamental one: “Work sucks.”

Uncovering how work sucks and how we can make it suck less is the task she sets out for herself and us in the book. First, Swift finds there are three main reasons that work sucks.

- Work Is Dangerous

- Work Is Dull

- Work Is Frustrating and Confusing

Rather than assuming all her readers are knowledge workers, Swift takes an industry agnostic approach to understanding why the reality of modern work is failing so many. “The answer is,” Swift finds, “again, threefold.”

- Work has intensified—workers are challenged to do more with less.

- Work is misunderstood and often misattributed—no one understands what really needs to be done, and thus the wrong people get credit.

- Work is performative—symbolic action has overtaken meaningful action.

So, if you feel like your work has gotten harder in recent years, that your boss doesn’t understand you or what you do, and you feel pressure to do things that get you noticed over doing actual work—or see that many around you are doing so—rest assured you are not alone. There is no one easy fix for this, which is perhaps why Swift offers ninety potential solutions, which range from “Strategy 2: Don’t take intensified work for granted—and don’t be afraid to de-intensify" to “Strategy 79: Don’t let your own career journey shape your assumptions about your team members (or potential hires).”

There is a lot to ingest here, but rest assured that it is an easy, interesting, and entertaining read, and you can open to almost any page in the book and find an idea you can start putting into practice today if you are willing to commit to it.

READ AN EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK HERE.

Working to Restore: Harnessing the Power of Regenerative Business to Heal the World by Esha Chhabra, Beacon Press

Esha Chhabra’s book may be the most unusual choice in this category, because it is not a book about management or workplace culture, per se. But it is, I hope, a harbinger of how we must rethink what constitutes both topics. Because it is no longer enough to focus on simply managing ourselves, other people in our organizations, and our bottom line. We must broaden management to include maintaining healthy relationships and resources outside the walls of our organizations, in our supply chains, our communities, and the environment.

When viewed more broadly, the earth is our workplace, and we have a responsibility to foster a culture of care for it within our organizations. In contrast to so many big businesses that are willfully blind to the abuses of people and planet that exist in their global supply chains, Chhabra highlights entrepreneurs and organizations that are getting up close and personal with the people who produce the base materials that end up in their products. They are people like Vikrant Giri, the founder of a company that makes custom tote bags who takes the time to travel to and know intimately the lives and needs of the farmers—some close to home in California but as far away as India—who he sources his organic cotton from. Like the other books in the category, Chhabra offers similar examples across many industries, featuring “entrepreneurs and companies are rethinking how food, fashion, travel, health, finance, and more can be made more regenerative.”

These are stories of entrepreneurs who are trying to restore civility, integrity, and transparency to business.

Again, these seem like bedrock management principles we’ve simply gotten away from more than a radical new perspective, which is the reason we put the book in this category over Big Ideas & New Perspectives. Indeed, Chhabra explains how these ideas aren't really new—”the term ‘sustainable development entered the lexicon,” she notes, in 1987—but they are hopefully ideas whose time has finally come. Some are even turning away from the word “sustainable.” Writing about Sébastien Kopp, cofounder of the shoe brad Veja, Chabbra writes:

He abhors the word “sustainable.” “We don’t do ‘sustainable,’ ‘ethical,’ ‘slow,’ or any other words used to describe alternative fashion. We just focus on being transparent and fair,” Kopp said.

Galahad Clark, of Vivobarefoot, went even further by stating, “Sustainable shoemaking is barefoot shoemaking.” But that doesn’t mean we can’t manufacture and wear shoes, or experience many of the other comforts industrialization has offered humankind. We simply have to shift how we manufacture and make things, get more intimate and knowledgeable about how our supply chains affects people and planet, and operate with as much respect for the dignity of both as we possible can. It will be imperfect, but we can make progress. We can manage it. Many, Esha Chhabra shows us, already are.

READ AN EXCERPT FROM THE BOOK HERE.