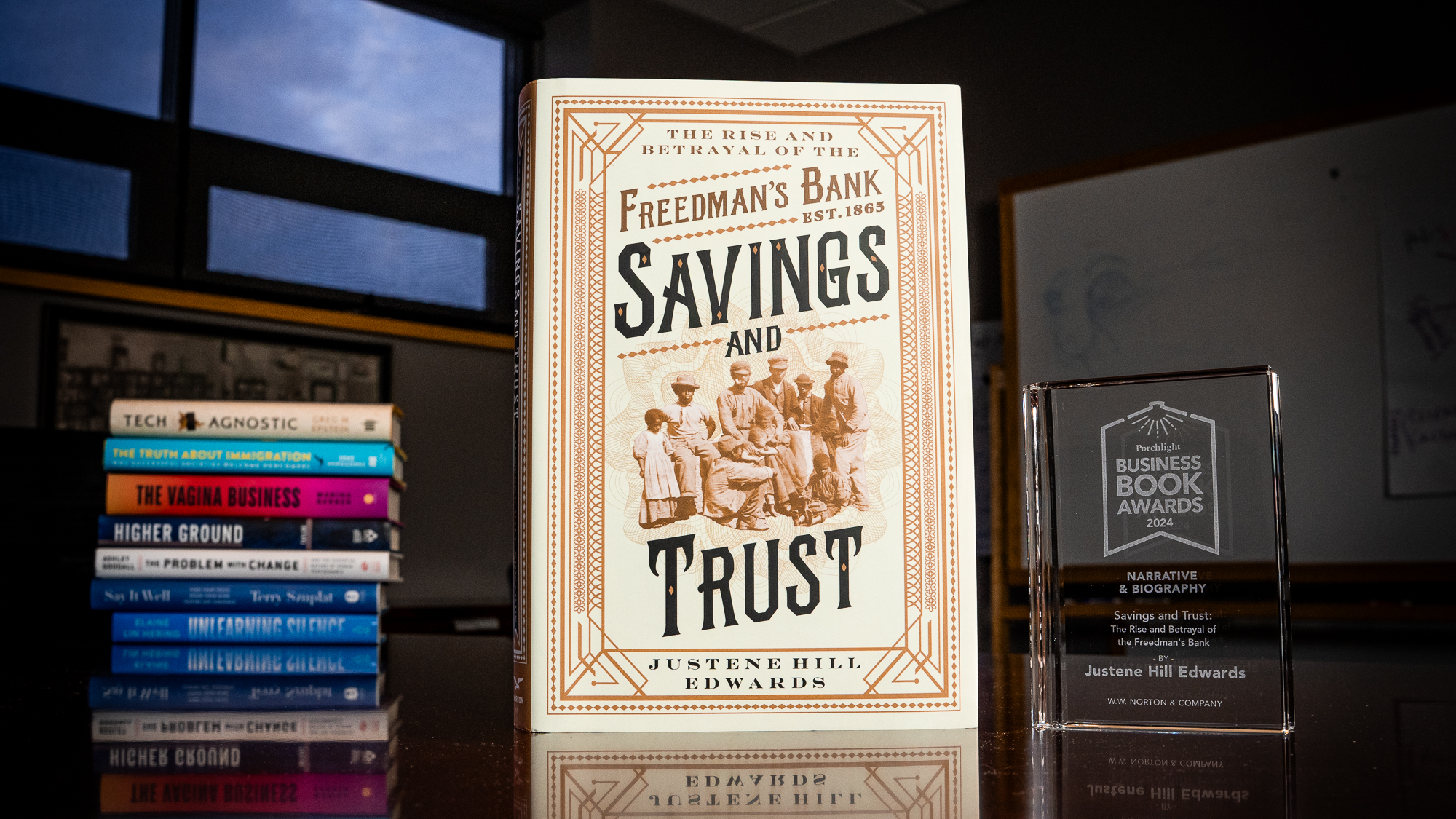

Savings and Trust | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Narrative & Biography Book of the Year

Writing about Savings and Trust in her post about the best narrative and biography books of 2024, Porchlight's Managing Editor Jasmine Gonzalez tells us how the story ends:

The Freedman’s Bank ultimately collapsed in 1874, with Black depositors’ money tied up in outstanding loans made to White borrowers, most of whom opted not to repay what they had received. They had effectively plundered the coffers. The wealth that Black Americans had built was gone. “For freed people,” Hill Edwards writes, the failure of the Freedman’s Bank “represented the failure of the federal government, elected officials, white capitalists, and even African Americans with economic and political influence to protect their economic interests.”

In the excerpt below, Justene Hill Edwards outlines the history of the Freedman’s Bank and the financial violence and theft perpetrated against the bank's depositors—discussing the different perspectives from which that history can be told.

There are various ways to tell the history of the Freedman’s Bank. One is from the perspective of people such as Enon and Epher Wright, African Americans who toiled and saved to buy themselves out of slavery. In many ways, the Wright brothers epitomized the dream of the almost four million enslaved men, women, and children who embarked on the harrowing trek to claim their freedom at the end of the Civil War. By patronizing their local Freedman’s Bank branch, the Wright brothers and tens of thousands of African Americans like them invested in their own economic futures.

Another perspective comes from the bank’s white administrators. Some of the abolitionists, bankers, and philanthropists, such as Mobile cashier C. A. Woodward, used the bank to demonstrate their support of freed people and their support of the newest banking infrastructure, which emerged during the Civil War. The new regulatory architecture, with a standardized currency, capital requirements for national banks, and a regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, was supposed to stabilize the national economy. White philanthropists in Northern cities such as Philadelphia and New York believed in savings banking as a vehicle to help the poor and working classes become self-sufficient. For these philanthropists, the Freedman’s Bank was a grand economic experiment in savings banking for former slaves just emerging out of the tribulations of bondage.

Yet another perspective comes from a figure who was the most visible Black man in America during the nineteenth century: Frederick Douglass. Douglass’s involvement with the bank temporarily marred his reputation as a Black man dedicated to African American political and economic advancement, especially for the formerly enslaved. His entanglement with the bank at the time of its demise was one of his greatest regrets. He would spend the rest of his life restoring his good name.

Savings and Trust explores these intertwined stories, telling the history of the Freedman’s Bank from the perspective of the freed people who invested in the bank as depositors, as well as through the experiences of the bank’s administrators. Fundamentally, the history of the Freedman’s Bank is the story of a web that connected the almost four million African Americans who strode proudly into the era of freedom in 1865 to white men at the highest levels of American finance and politics. Whether they opened accounts or not, African Americans used the bank to test whether the federal government would make good on the promise to protect freed people and to extend them citizenship and voting rights. The bank became a proxy for the federal government’s commitment to the ideals of the Civil War. At a fragile moment in the history of the American republic—the reconstitution of a nation obliterated by the violence of civil war—the Freedman’s Bank represented the economic potential of the nation’s formerly enslaved people. It was animated by the benevolent work of white bankers and philanthropists, supported by congressional Republicans and the federal government more broadly. The bank was supposed to symbolize the twin engines of capitalism and democracy made manifest.

Instead, Black people’s generational distrust of financial institutions can be traced to the founding and failure of the Freedman’s Bank. African American depositors could not escape the rapaciousness that defined Gilded Age capitalism. White bankers pillaged the bank, mishandling and stealing Black depositors’ savings in the process. African Americans’ economic livelihoods were at stake, and the bank’s demise bankrupted Black communities across the nation. In the end, they were the victims of white capitalists’ greed. Their experiences with the bank, and the federal government’s unwillingness to hold the perpetrators accountable, represented an underexplored aspect of the white racial violence that characterized Black people’s lives in Reconstruction and during the Gilded Age.

Historians familiar with the Civil War and Reconstruction eras are aware of the Freedman’s Bank and its history. But the story of the bank has often been an addendum, or sometimes a literal footnote, in larger accounts of a nation emerging out of the vagaries of war. Savings and Trust places the Freedman’s Bank at the center of a larger narrative about Reconstruction and the economic aspirations of millions of African Americans. It also illuminates the extent to which America’s banking industry has preyed on the nation’s most vulnerable populations. During Reconstruction, it was the millions of African Americans recently emancipated from slavery who were the victims of the financial industry’s predation.

Established on March 3, 1865, and signed into existence by President Lincoln in the month before his assassination, the Freedman’s Bank grew steadily in its first five years, with depositors from New York to New Orleans opening accounts and depositing their hard-earned savings into the bank’s coffers. Between 1865 and 1870, African Americans deposited a total of $12.6 million ($303 million today) into accounts at branches in states as far north as New York, as far south as Florida, and as far west as Texas. By 1870, depositors had earned over $1.6 million ($38.5 million today) from the bank in interest payments on their deposits.

Black depositors received clear messages from administrators about the advantages of saving money. These trustees and branch cashiers were Republicans who not only actively supported the Union’s war efforts but also supported a free labor ideology that infiltrated the bank’s advertisements within Black communities with bank branches. “Save the Small Sums—Cut Off Your Vices—Don’t Smoke—Don’t Drink—Don’t Buy Lottery Tickets—Put the Money You Save into the Freedman’s Savings Bank,” were splashed in Black newspapers and disseminated in Black communities across the nation, primarily in the former Confederate South. Designed to persuade depositors that morality and saving went hand in hand, the bank’s predominantly white administrators worked to convince Black people to patronize local branches and deposit as much money as possible into bank accounts. The messages—and the propaganda—communicated to freed people that banking would help them climb the ladder to full freedom.

By 1874, depositors had collectively placed over $57 million ($1.51 billion today) into over one hundred thousand bank accounts in thirty-four branches. By anyone’s estimation, freed people made the Freedman’s Bank one of the most successful financial institutions of the nineteenth century. For a short time, African Americans used the bank to build a stable economic foundation for themselves and their families after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished legal slavery in 1865. During this time, the Freedman’s Bank epitomized the economic power of African Americans unleashed from the bonds of enslavement.

In their public-facing messaging, the founders and trustees of the Freedman’s Bank wanted to democratize finance, to make banking accessible to working-class and poor people. Bank officials believed that they needed to teach freed people about banking and finance to help them understand the responsibility and burden of freedom. This message formed the core of the bank’s mission. The trustees and administrators circulated public messages to freed people about the federal government not helping them economically in their climb out of slavery. They urged Black people not to rely economically on the federal government and instead to cultivate a sense of self-sufficiency. By working for the bank and guiding its mission, administrators were agreeing to help freed people navigate the economic minefield that defined Reconstruction.

Bank administrators, however, did not fulfill the terms of their promise to depositors. Instead of offering simple banking services to freed people, the trustees decided to take a gamble. First, it was an illegal loan to a trustee in April 1867. Then, in May 1870, the bank’s predominantly white trustees, led by famed (and infamous) banker Henry D. Cooke, lobbied Congress, which allowed them to alter the bank’s fundamental mission.

By mid-1870, the bank ceased operating as a savings bank or, as the bank’s name suggested, a savings and trust company. The trustees, with congressional approval, began to operate the Freedman’s Bank as a commercial bank. Instead of merely accepting freed people’s deposits, the trustees began making loans, using the millions of dollars of Black Americans’ money to invest in speculative ventures. Most of the loans went to white businessmen, members of Congress, and investors in and around the bank’s central office in Washington, DC. Some of the trustees even stole depositors’ money to fund their own business ventures. Initially, when the bank operated as a savings bank, the trustees’ and administrators’ intentions may have benefited the depositors. But as African Americans’ money flowed into their accounts, the bank administrators’ intentions changed. Corruption seeped in. This corruption jeopardized the bank’s fundamental mission, to serve African Americans.

The bank could sustain only so much instability. So when a financial panic in the fall of 1873 toppled some of the nation’s most prominent financial institutions, this event proved to be too much risk for the Freedman’s Bank to withstand. The trustees, therefore, made one final decision to salvage the bank’s reputation among Black depositors. In March 1874, the trustees convinced Frederick Douglass to help steer the bank toward prosperity. But not even Douglass could rescue the institution, or the depositors’ money. After nine years of operation, the bank’s exponential growth came to an abrupt stop. On July 2, 1874, the bank officially closed its doors. The remaining depositors, all 61,144 of them, lost access to a collective $2,939,925.22 ($77.9 million today). Though depositors recovered $1,731,845.01 ($45.9 million today), 59 percent of the total deposits at the bank’s closing, by 1909 depositors still had $1,208,071 ($40.1 million today) outstanding that they had not received. The damage was done. Freed people received clear messages about their value in the financial services marketplace. Though slavery was no longer legal, white capitalists could exploit them and their hard work, and they would have little recourse.

Savings and Trust charts the rise, expansion, and untimely collapse of the Freedman’s Bank. It also illuminates the multifaceted violence of Reconstruction. Though white racial terrorism against African Americans, especially in regions of the former slave South, is well documented, physical violence was not the only form of terrorism that white Americans waged on freed people. The bank’s plunder by white bankers, financiers, and capitalists was brutal. While not the interpersonal atrocities that white vigilantes pursued against freed people, the strategic pillage of the Freedman’s Bank by white capitalists represented another type of violence against African Americans. It encompassed the ruthlessness of capitalism left unchecked. It was the financial violence of theft.

Through interrogating the bank’s inner workings, including the machinations of the bank’s trustees and administrators, Savings and Trust shows how a small well-connected group of men—some wealthy and some naïve—built the bank up and tore it down, with over sixty thousand freed people in July 1874 losing their economic safety net in the process. African Americans such as Enon and Epher Wright put their faith—even their trust—in the Freedman’s Bank, and in the institution’s trustees, administrators, and cashiers. And after the Panic of 1873 and the bank’s closing, the white men of finance and economic means came out of the financial collapse on firm ground. They reestablished their reputations. They found new ways to build their empires.

Excerpted from Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank by Justene Hill Edwards. Copyright © 2024 by Justene Hill Edwards. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.