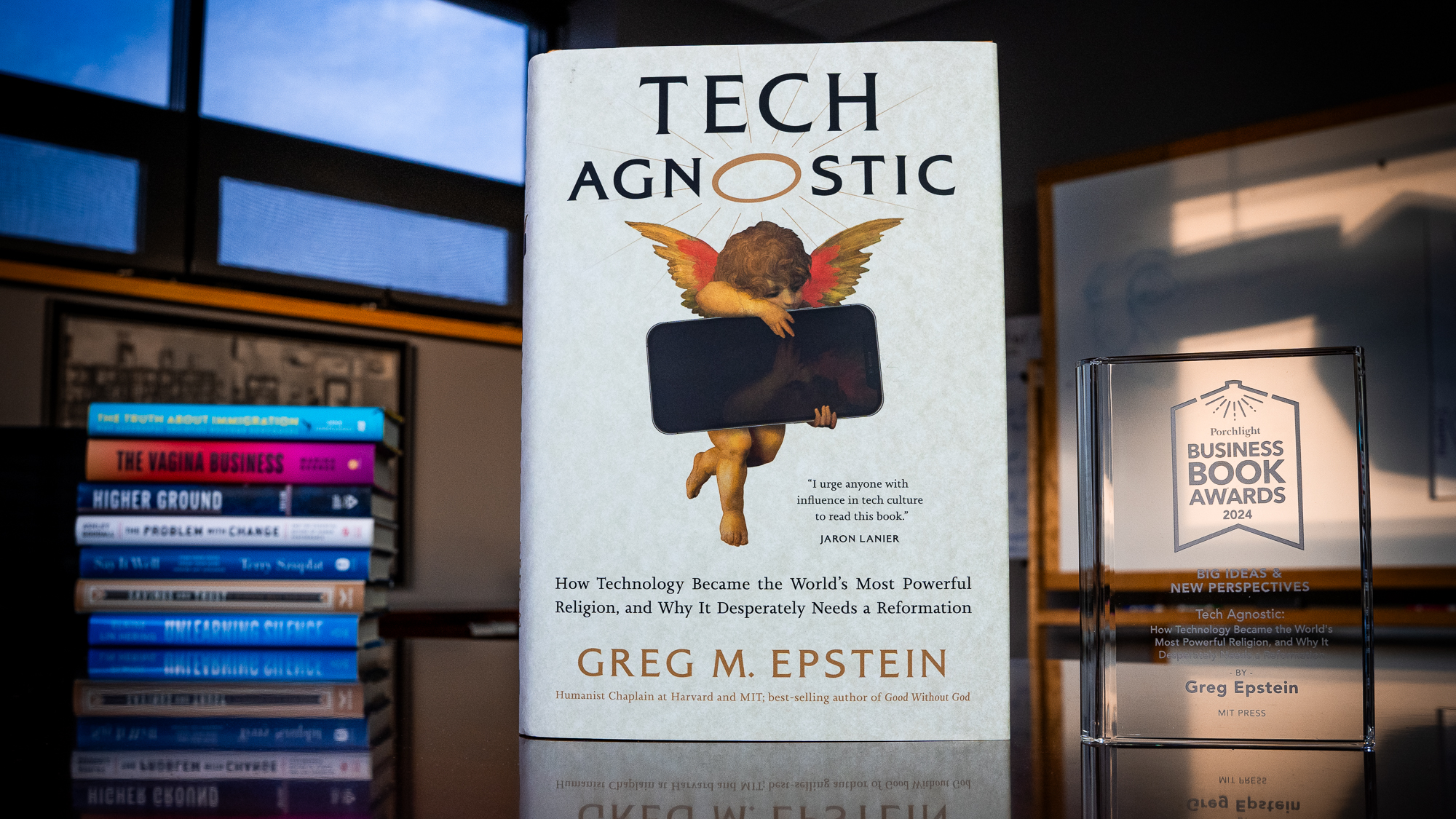

Tech Agnostic | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Big Ideas & New Perspectives Book of the Year

In her review of Tech Agnostic for the post about the best big ideas and new perspectives books on 2024, our Managing Editor Jasmine Gonzalez wrote:

Why might we think about our relationship with tech through the lens of religion? “Like traditional religions once did,” writes humanist chaplain Greg Epstein, “technology is shaping our thoughts, feelings, hopes, fears, relationships, and future.” Just as people have believed in the omnipresence of otherworldly deities, tech is everywhere: in our homes, workplaces, all the spaces in between, and the modes of transportation that get us there. Whether we realize it or not, we have built rituals around our tech, checking our phones as soon as we wake up and in the final moments before we fall asleep.

In the book's Introduction, Epstein writes of how “a tech culture that began as a garage project for nerdy dropouts has become the driving force of our entire civilization." That is indisputable, but can it really be considered a religion?

WHAT IS TECH, TODAY?

Most people would say tech is an industry, but that’s an absurd statement, because every industry in the world is now a tech industry. “We’re in a period where tech has expanded to take over nearly every aspect of our lives, economically, socially, and politically,” said Mar Hicks, an award-winning historian of technology, specializing in the history of computing, when I asked them just how big technology is today. “And that’s due both to the ever- expanding definition of what we consider tech to be, as well as to the real and intended consequences of overfunding an industry and a field of study— computer science— that has long promised people the ability to escape reality and even more importantly to control their environments.” Indeed, the size and scope of tech has grown so difficult to quantify that when I asked a similar question of Jason Furman, a Harvard economics professor who served President Barack Obama as chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), he acknowledged that even traditional measures such as gross domestic product (GDP) and stock valuations don’t do justice to the exalted status of technology in our world. As Furman pointed out, one could calculate the fraction of GDP (or “value added”) in technology companies, but that “doesn’t count the ways that General Motors, J. P. Morgan, and the corner store all use technology to produce what they produce.” Tech stocks would represent an even higher percentage of the $50 trillion of stocks overall, Furman wrote to me in fall 2023, but even such a measure “doesn’t count GM, JPM, and the corner store.” The distinguished economist ultimately suggested I might simply stick, without quantification, with Mar Hicks’s definition above— that tech has taken over nearly every aspect of life— because, as Furman said, it “seems true.” “Tech, and the tech industry,” Hicks continued in their email to me, “is largely about power and control. In the best-case scenario technologies can be force multipliers for good— think sanitary sewers, or heart stents, or easier-to- operate wheelchair designs. In the worst- case scenario, they multiply force in incredibly violent, destructive ways— think sarin gas, firearms, or the atomic bomb.”

✵

We wake up, and before our smart mattresses or smart watches can stop monitoring our every sleeping heartbeat and breath, our smartphones light up as we check them for the first time that morning. Male Orthodox Jews are required to thank God they are not a woman (among other prayers) upon exiting their bed. Many of us, immediately upon rising, stare at our smartphones, performing our own strange rituals. These may or may not include cursing God for our Twitter (“X”) feed.

Phone still in hand, where it will remain for much of the day, we stumble to the bathroom, where we might, if we’re lucky enough to afford one, brush our teeth with a smart toothbrush or clean ourselves with a smart toilet. In the kitchen, we barely notice our smart refrigerator or smart dishwasher, but our network sees them. Our smart doorbell, watching vigilantly for intruders, lets us know whether we have achieved “fulfillment” . . . in the form of our Amazon package having been successfully delivered. The smart thermostat adjusts itself for our comfort. If your kid is like mine, they haven’t eaten breakfast and are running late for school because they’re mesmerized by whatever slop the YouTube algorithm is feeding them. Maybe we share a witty TikTok or notice an Instagrammable moment on our way to work or school. Or perhaps we’ll never make it to a physical workplace at all, because we’re working from home or even from a beautiful beach we barely notice, thanks to a constant pinging of Slack messages. Or maybe generative AI has made redundant our role as a coder, paralegal, financial analyst, graphic designer, or even teacher.

However we choose to spend our day, one thing is clear: Not only will we be surrounded by intelligent products, each created to perfectly optimize every detail of our environment. Ultimately we are the product that must be optimized, less for our own benefit than for the glory of technology itself. As such, our daily existence will be tracked constantly by a thousand cookies we have accepted so that they might follow our movements, our moods, and our purchasing power.

At night maybe we’ll stream the news from a podcast or scroll through headlines on our feed, feeling depressed and anxious about the fate of a world continually under attack by rogue forces using the Internet to manipulate, disinform, and stoke hatred for clicks. Maybe that will trigger us to binge on the artisanal ice cream or vodka that we bought because the brand microtargeted us for an ad while we were shopping on Instacart. Eventually, eyes and brains aching from an overdose of ultraviolet light, we’ll log off. Until we do it all again tomorrow.

Today technology is the water in which we swim, whether or not we notice we are fish. Tech provides contemporary Western lives, so polarized and divided in countless ways, with a universal organizing principle, a common story by which we tell ourselves who we are. It offers myriad rites, capturing our attention and transforming our consciousness, connecting us with a community of people who spend their days, weeks, years, and indeed their entire lives engaging in the same repetitive behaviors with the same fervent intensity. Naturally, we all hope our devotion to this communion of fellow travelers bears fruit: surely tech will lead to a better future! Even a kind of paradise! But the truth is that many of us fear, more than we’d like to admit, that this may all be heading to a deeply dark place.

In other words: technology has become religion.

Excerpted from Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World’s Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation by Greg M. Epstein. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2025.