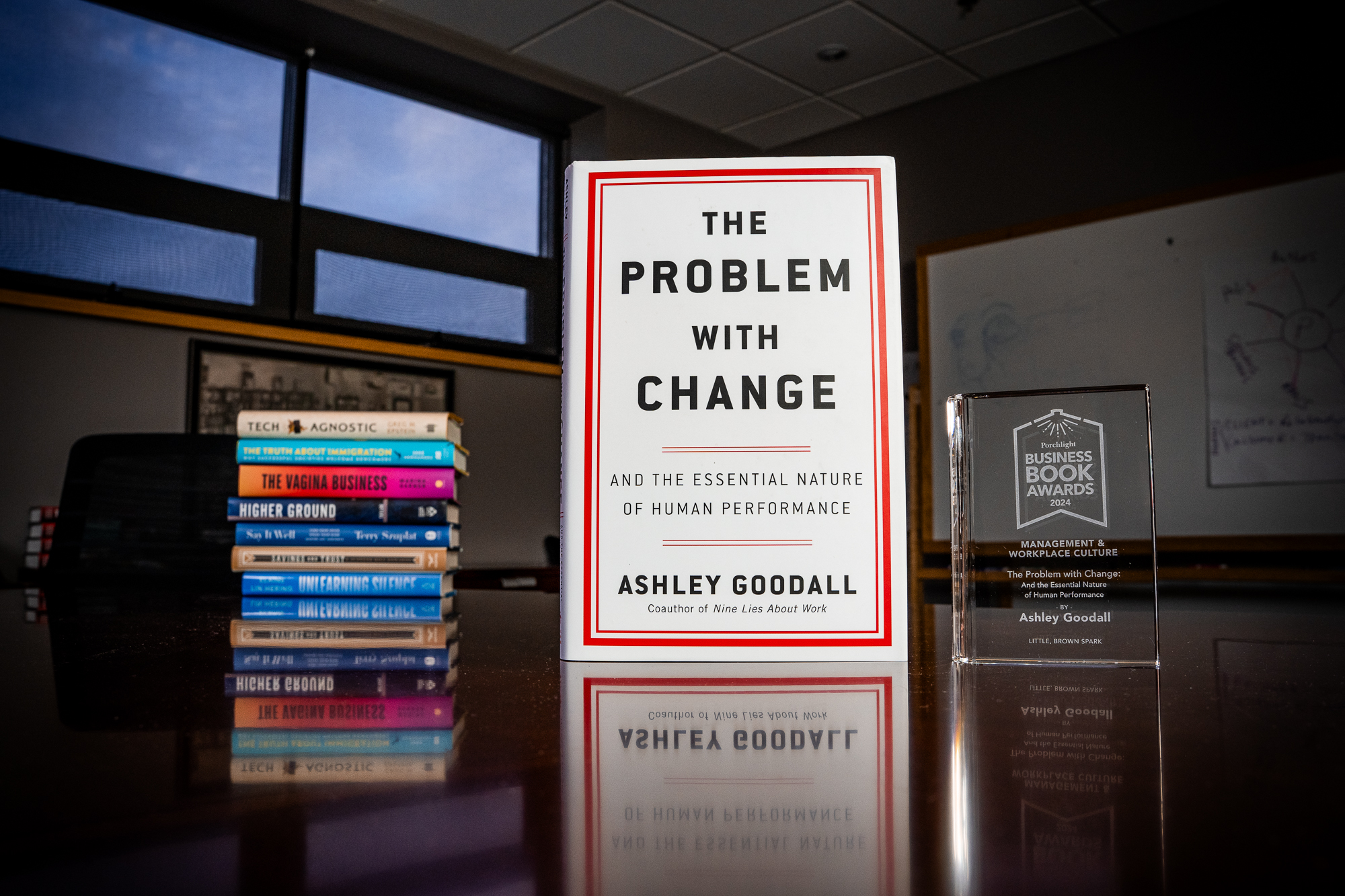

The Problem with Change | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Management & Workplace Culture Book of the Year

Reviewing The Problem with Change in a post about the best management and workplace culture books of 2024, Porchlight's Marketing and Editorial Director Dylan Schleicher wrote:

It is almost a prerequisite for any leadership candidate to have a change plan. Rather than focusing on improvement or stability, supporting workers and connecting them to a larger goal or each other, it seems that the job of leaders today is just to change things. We have become obsessed with disruption—not just the threat of it from outside our organization, but the necessity to disrupt our own operations before others can.

In the excerpt below, Ashley Goodall explains how he became "skeptical of change" and its effects on workers, and questions why it has become such a unquestioned goal of most organizations.

Life inside many companies today feels like an endless procession of upheavals, each unleashing another torrent of change and rearrangement and reconstruction, each once again reshuffling all the pieces into some supposedly more desirable configuration. This is life in the blender. And while it’s not always the case that all the blender buttons get pressed at once—not every merger is followed by a reorganization, for example, and not every strategy change leads to an operating model change—it’s a rare organization that goes for very long without at least a quick blitz here and a little pureeing there.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve seen this firsthand. As a fledgling management consultant, I sat in a cube at our client’s offices while a merger announcement upended the lives of the people around me. As a junior HR professional, I saw a year’s work for dozens of people tossed out when an incoming leader wanted to do things her own way. As I moved through the ranks, I accumulated more examples, both big and small: the frustrations at a new piece of technology, when the old one seemed to work just fine, or at the new approvals process that seemed to slow everything down; the relocation of a department from one building to another, because efficiency, and then back again, because no one was quite sure why; and all the Reinventions and Transformations and Reboots and Resets and rosy promises and rolling eyes. And then, as a senior HR executive at Deloitte and then Cisco, I saw more closely than ever before the chasm that change can create: the leaders, impatient and frustrated at the inability of those in the trenches to get with the program; the people on the ground, exhausted by the latest initiative or innovation, and frustrated at how hard it was simply to get on with their daily work.

I emerged from these experiences skeptical of change. Not always, but certainly when it struck me that change was happening for the sake of change, or that change was making things worse rather than better, or that change was making things murkier rather than clearer. Of course I had learned early on in my career to say with great regularity how excited I was about change and how incredibly comfortable with ambiguity—as many of us had learned to say—but as the years went by, I found myself feeling that the truth was more complicated. In my two decades working in large organizations, I’d seen change that had unquestionably led to better results and better work and better experiences; at the same time, I’d seen plenty of change that was a disaster for all concerned, and that extracted a heavy toll from individuals, and teams, and ultimately from organizations themselves. Yet no one seemed to question the notion that change was always and necessarily a Good Thing.

So I set out to dig a little deeper. This book contains what I have discovered.

[…]

I spoke to dozens of people about the topic of change. Interestingly, I had not asked them to tell me what was bad about it, but rather just to share their stories. Nevertheless, with only a couple of exceptions … the experiences people shared were overwhelmingly and arrestingly negative.

There were some patterns in the various stories. Many, but not all, started with a merger, or an acquisition, or a divestiture—the sorts of God- game moves beloved of the activist investors and investment bankers and management consultants. Almost all involved some sort of reorganization or leadership change. Many touched on layoffs and their impact, although layoffs were seldom the main event — in most cases, they followed a reorg, or a change of leader, or some type of M&A activity. Several people talked about the way in which the environment at work only amplified the large amount of turmoil in the world in recent years. Said one, “People are so on edge, because everything is so unpredictable in the external world. And then they come to work, and they’re like, ‘Oh, wait, more unpredictability. Really?’”

All the stories I heard were of change extending over months and usually years; although we might think of change as a discrete event, it has become instead an ever-present feature of the working world, such that if we are not embarking on a new change initiative, it’s only because we’re still digesting the last one.

And in exactly none of the stories did a leader reconsider his or her course of action once it had been embarked upon. Large-scale change follows a strikingly consistent pattern: Once triggered, it takes on a life of its own. There is no way, apparently, to get halfway through and think better of it; instead, organizations and their leaders become captive to their own change efforts. Sometimes this is even by deliberate choice: Many of the leaders in these stories seem to think that having the courage of your convictions is the same as ignoring the mounting evidence that things have gone awry.

This—the uncertainty, the turmoil, the exhaustion, the disempowerment, the disengagement, and the slim and tenuous hope that it will all be okay in the end—is organizational change in action, and it’s very hard to come away from conversations about it without questioning the proposition that the way we do change today is by its very nature a good thing, and that change itself is an unalloyed good. This point holds

not just for the people on the receiving end, but also for the companies that instigate these sorts of changes. If you talk to the people on the front lines, the stories you hear are not of suddenly increased innovation or productivity or efficiency, but rather of desperate efforts to steady the ship and keep it afloat. It’s also hard to overstate the extent to which this is work today, so thoroughly have our ideas about the unimpeachable virtues of change colonized our workplaces and the thinking of those who shape them.

At the same time, however, a few of my conversations hinted at a more complex reality. At the end of a recitation of one upheaval after another and their combined effect on morale and sanity, an interviewee would pause, and I would ask if they felt, then, that change was, as we are so often told, a good and necessary thing. And they would brighten and smile and say yes, of course, because change is essential and without it the world would be an infinitely more somber place. “I believe in potential, I believe in possibility,” said one person, “and change is required for potential to happen. So I’m willing to see the possibility within the change.” But if I then asked my interviewee to explain that sentiment in light of the experiences they had shared—in light, that is, of how change actually, rather than idealistically, unfolds—they found this hard to do.

This points to a conundrum at the heart of change. Leaders, for the most part, aren’t launching disruption because they enjoy inflicting pain on people. Those in the trenches struggle to reconcile their experiences of change with their intuition that it is sometimes a good thing—or at least, that it should be—and most of us, I think, would agree that change is needed in some circumstances. Why, then, is such a supposedly good thing so often so miserable in practice? And, for that matter, how did we all come to agree that it is such an unquestionably good thing in the first place?

Excerpted from The Problem with Change: And the Essential Nature of Human Performance by Ashley Goodall, published by Little, Brown Spark, an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group. Copyright © 2024 by Ashley Goodall. All rights reserved.