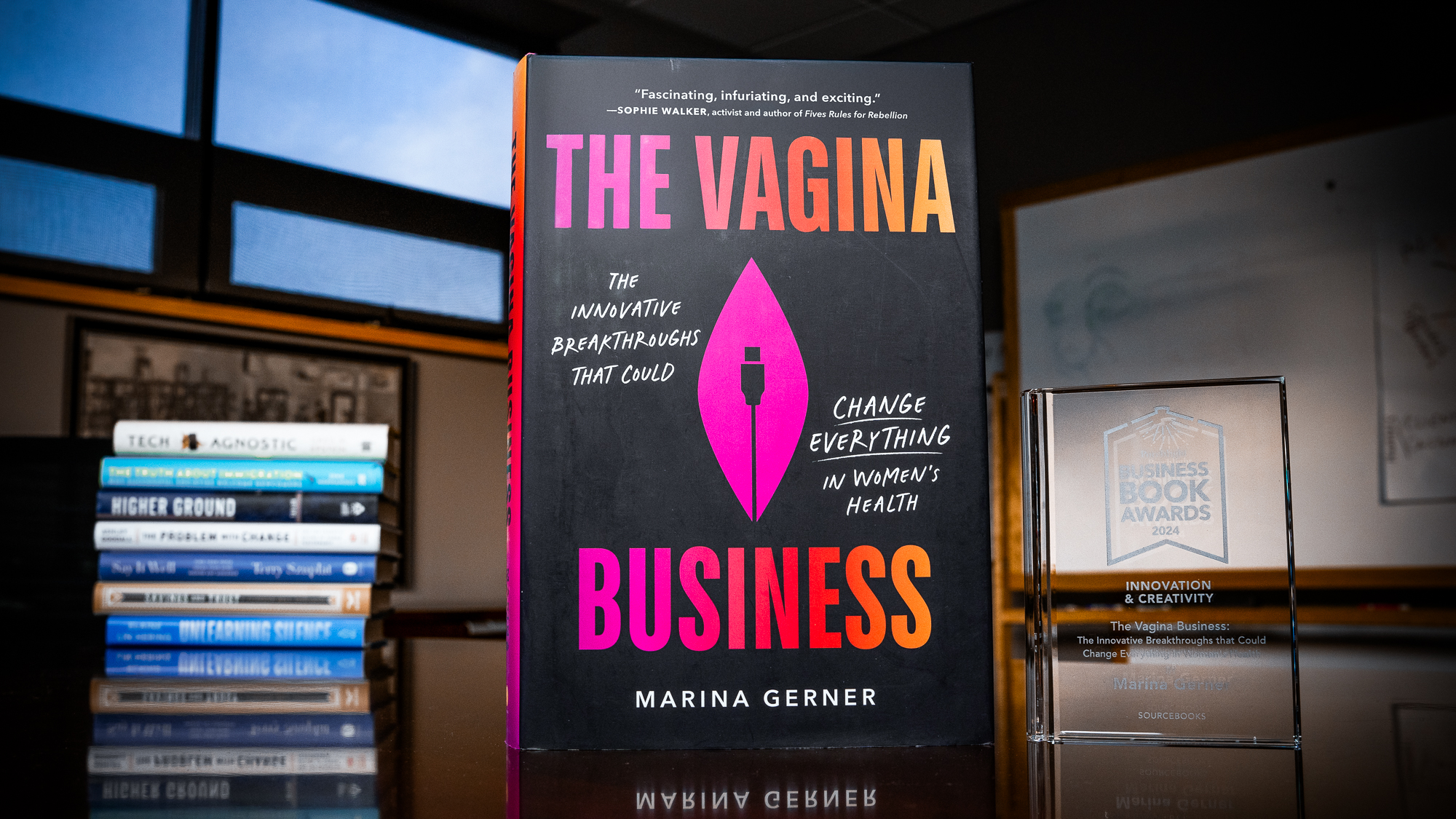

The Vagina Business | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Creativity & Innovation Book of the Year

In her post about the best creativity and innovation book of 2024, Porchlight's Creative Director Gabbi Cisneros wrote:

While we’ve read a lot about how gender inequality manifests in workplaces as pay gaps and sexual harassment, The Vagina Business illuminates how the entire healthcare system–its research, products, and personnel–are practicing and upholding inequality as well. By including the stories of entrepreneurs paving the way in women-centric, healthcare-related innovations, the book shows that there is a lot of incentive for women’s health research, and it empowers readers to change the way that women’s bodies are (or are not) discussed and valued.

In the excerpt below, Marina Gerner discusses how, even though women make the majority of healthcare decisions in the U.S., they have been largely ignored and unseen by its healthcare system—and the innovations occurring that can hopefully change that fact.

Women make 80 percent of healthcare decisions in the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, but are hardly involved in the design of the healthcare system. It was only in 1993 that women and people of color were officially included in U.S. clinical trials, and much of our current medical knowledge has been shaped by earlier research. Women were long excluded from research because of our cycles; even animal testing tends to exclude female mice, because of their hormones.

The consequences have been catastrophic. Women are 50 percent more likely than men to be given a wrong diagnosis after a heart attack. Across 770 types of diseases, women are diagnosed an average four years later than men. And a delayed diagnosis means women are more likely to suffer pain and complications.

Female-specific diseases are met with a raised eyebrow, as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is routinely misdiagnosed. It can take close to a decade to get a diagnosis for endometriosis. Even Oprah was repeatedly misdiagnosed when she had heart palpitations as part of menopause.

The dosage of most drugs is calculated based on studies overwhelmingly conducted on male participants, even though in women, drugs tend to linger longer, as our liver and kidneys process them differently.

Only 4 percent of all healthcare research and development is focused on women’s health issues, according to PitchBook data. In the UK, less than 2.5 percent of publicly funded research is dedicated to reproductive health and childbirth. Women’s health is both underfunded and underresearched.

This disparity has existed for millennia. In ancient Greece, people believed women’s health problems were caused by our uterus wandering around our body; say if it got stuck in the chest, we’d have chest pain. In the nineteenth century, doctors blamed “hysteria,” which comes from the Greek word hystera for “uterus,” as a cause for female health issues.” Today, women continue to be brushed off for “complaining.”

Female pain has been normalized, from childbirth to menopause, as society shrugs and says “Welcome to being a woman” instead of coming up with better solutions. The terms we use are revealing. There’s nothing quite like “morning sickness” to trivialize what can be a debilitating experience in pregnancy, confined not only to the morning. Another contender for outdated terms is “geriatric pregnancy,” which sounds bleak and is also oxymoronic, as you can’t be ancient and fecund. We don’t say, “Here’s your geriatric pack of Viagra.”

Female bodies have long been shrouded in mystery, and those who work in related fields continue to face stigma. In a speech Virginia Woolf gave in 1931, she said it would still be decades before women could tell the truth about our bodies. To this day, our culture and the attitudes—of both men and women—stand in the way of innovation and of how we as women relate to our own bodies. As data is slowly catching up with reality, could a burgeoning group of innovators help to plug the gap?

Vagina innovation

Let’s not forget that the business world is a reflection of our culture. Think about the way we use language. Calling somebody “a dick” is commonplace, but try shouting “vagina” in a pub. A figurative fear of vaginas can be traced back to folktales of the toothed vagina, the vagina dentata, throughout history. This fear was central to Freud’s idea that men suffer from castration anxiety. Today, many femtech entrepreneurs I’ve spoken to encounter what they describe as “a fear of vaginas.”

We can find “vagina ghosts” haunting ancient Japanese woodblock prints. But there’s no direct Japanese word for “sexual wellness,” notes Amina Sugimoto, the founder of Fermata, online marketplace for femtech products in Japan and Asia. While dick doodles grace public bathroom walls around the world, most people can’t draw a clitoris.

To begin with, words like “vagina” are tricky for many people. Just by reading the word “vagina,” you may feel awkward, excited—or both. Many of the entrepreneurs echo the words of Tracy MacNeal, CEO of Materna, a company that has developed a dilator that pre-stretches the vaginal canal to make vaginal birth easier and faster: “When I first saw the product, I thought, ‘Don’t be ridiculous. Do I want to be the CEO of Vagina?’ But then my sister said, ‘You just feel this way because society has not valued vaginas.’ So, I realized I have to start with myself.”

Despite my liberal upbringing, I’m not immune to societal norms either and catch myself participating in them. Why do I whisper the word “period”? When asked for a period pad at work in the past, I have passed it on surreptitiously in an envelope, as if I’m dealing drugs. Gloria Steinem imagined that if men had periods, “menstruation would become an enviable, boast-worthy, masculine event,” but we still have some way to go. Businesses thrive when people recommend products to each other, when we tell our friends about this new meditation app or that massage hammer we enjoy. Of course, somebody’s period is a private matter, but how can a business thrive in an area most people talk about in whispers, if at all?

Our prejudice runs deep. In an experiment, researchers at a university in Colorado recruited a group of participants aged seventeen to thirty-six, who were told they were participating in a study on “group productivity.” They were told that they would be solving a problem together with another person. What they didn’t know was that this other person, a woman, was part of the experiment. At one point during the task, she reached into her handbag to get some lip balm and instead fumbled out one of two things onto the table: either a wrapped tampon or a hair clip. After the task, researchers asked participants to evaluate their partner. The women who dropped the tampon as opposed to the hairclip were rated to be less competent and less likable by participants.

Privacy is one thing; shame is another. Lift one strand of shame, and you’ll be pulling up a whole web of it. In a survey, Ingrid Johnston-Robledo, a researcher on body shame, has found that women who agree with the statement “I am embarrassed when I have to purchase menstrual products” were also more likely to say, “I think pictures of women breastfeeding are obscene.” Sadly, they were also less likely to have the ability to advocate for their own sexual pleasure. In other words, shame about the female body inhibits sexual agency. Entrepreneurs in the sextech space face a complicated web of shame that entraps potential customers, and this, in turn, influences how they conceive of and promote their products.

At the same time, there is a huge opportunity for companies to reach people who are looking for quality information and innovative products. Two-thirds of women between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four are too embarrassed to use the word “vagina” at a doctor’s office, according to a survey by the Ovarian Cancer Action, a British charity. It’s likely that these same women would feel more comfortable if they could seek answers through an app or a community of like-minded people.

The other issue is that there is no legacy of knowledge. Information about pelvic floors, for instance, is not typically passed down the generations together with the family heirlooms. Instead of talking openly about pelvic floor issues like incontinence, people use euphemisms. “After I gave birth, my mum would say ‘Lie down,’ and she wouldn’t tell me why,” says Gloria Kolb, the founder of Elidah, which provides a noninvasive therapeutic device for stress urinary incontinence. “It wasn’t until after I started my company that I found out she had two pelvic floor surgeries herself. I asked: ‘How could you not have told me any of this?’ She was just like, ‘Eh, you don’t talk about it.’”

“Nobody tells you, right? Nobody tells you about these phases in life until you’re there and you don’t even know what you don’t know,” said Mridula Pore, CEO and cofounder of the healthcare app Peppy, at a Women of Wearables event.

“People are realizing the same things over and over in each generation, but they’re not putting it somewhere in black and white,” says Rob Perkins, cofounder of OMGYes. This means companies in the space have an opportunity to provide access to trusted information, at a time when people turn to Google with mixed results.

If we continue to avoid talking about female bodies, by shrouding them in mystery, we rob women of pleasure and inflict them with pain. Juliana Garaizar of angel fund Portfolia was presenting Materna’s birthing device to a group of investors in Houston. Shortly before the meeting, a colleague warned her, “There is no way we can put this slide on.” But Garaizar insisted. “If there is one slide we should be showing—it is this one!”

As expected, the slide caused a ripple of giggles to run through the crowd. What they were shown was a photo of a vagina torn after childbirth compared to a healthy vagina. For too long, women’s pain has been ignored, from endometriosis to childbirth and breastfeeding. We can no longer let giggles get in the way of female health. It’s time for Eve’s curse to become a blessing.

Excerpted from The Vagina Business: The Innovative Breakthroughs That Could Change Everything in Women's Health by Marina Gerner, published by Sourcebooks. Copyright © 2024 by Marina Gerner. All rights reserved.