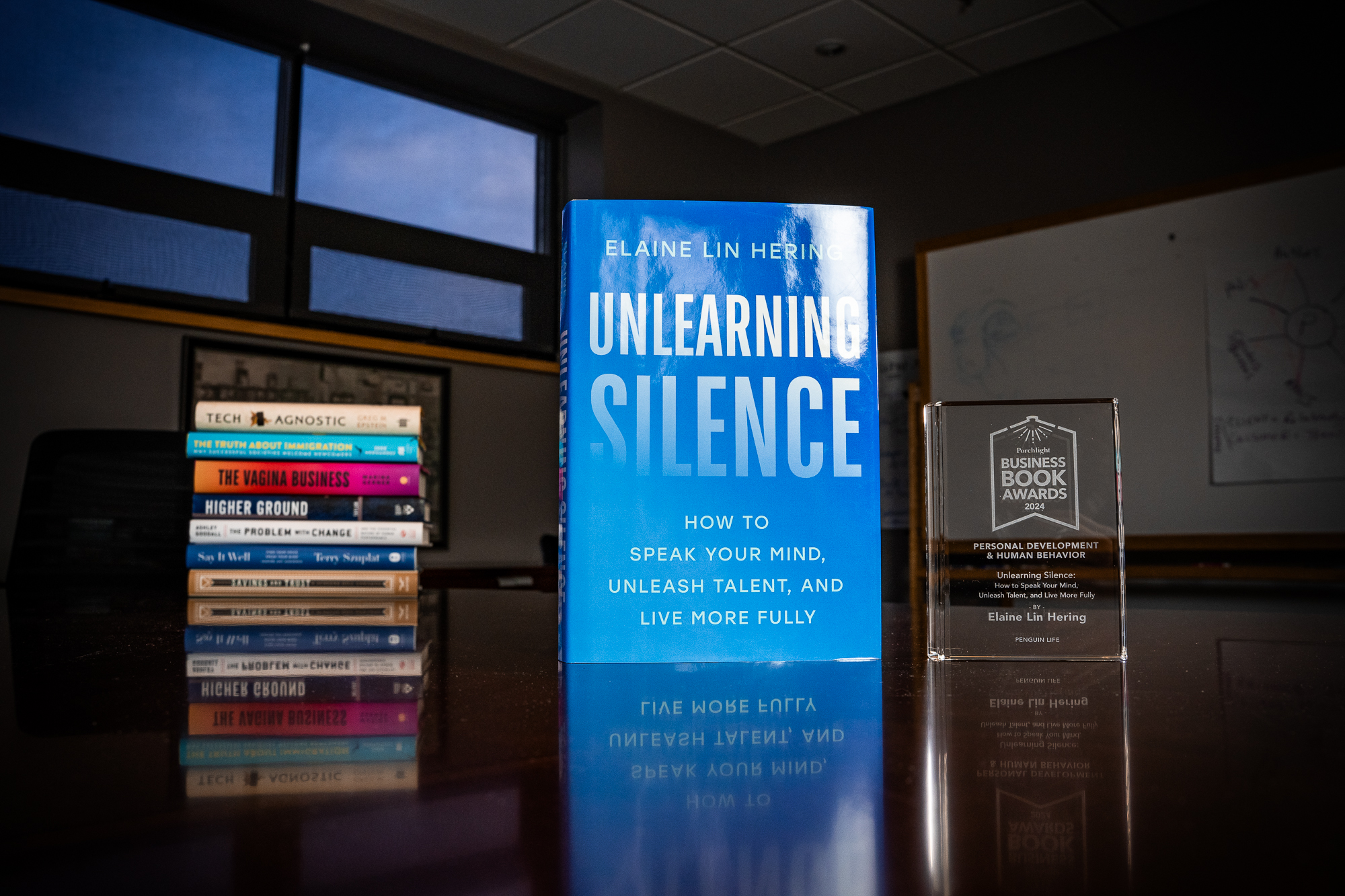

Unlearning Silence | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Personal Development & Human Behavior Book of the Year

Writing about Unlearning Silence in a post about 2024's best personal development and human behavior books, Porchlight's Creative Director Gabbi Cisneros noted:

Lin Hering eloquently explains how the consequences of staying silent can be much more detrimental than just getting passed up for a promotion. Silence and silencing others keeps systems of inequality in place, allowing people already with power to maintain or gain more power, and keeping everyone else at bay.

In the excerpt below, Elaine Lin Hering discusses the pervasive influence and role silence plays in our everyday lives and work.

Most organizations and social groups are homogenous. The majority of large companies in the Western world are still predominantly White. Many global companies still have White male leadership. White patriarchy—Social organization in which White men hold primary power and privilege—remains rampant. Yes, I did just say White patriarchy—and I’m well aware that it may make me too radical or political in your mind. But homogeneity leads to norms and cultures that don’t support all identities. Even when there are a few non-White, nonmale players at the table, their actions (or silence) most likely support the norms of the majority—by design.

This challenge of who determines what’s appropriate and acceptable isn’t limited to the workplace. Change how you look, what you eat, what you find funny—then maybe the social club or friend group will accept you. We segregate ourselves based on how much money we make, what political and religious views we hold, and who we feel comfortable around. (Economists and sociologists would have me say “sort” ourselves rather than “segregate,”6 but if the impact is actually segregation, let’s call it what it is rather than silence reality.) The communities we live in and the villages we form have the power to support or silence the very parts of ourselves that make us, well, us.

I would know. Since immigrating to the States, I’ve been on a decades-long journey to fit in. My parents had the privilege of choosing which neighborhood to live in. They chose White suburbia rather than an ethnic enclave and gave me a westernized name because it would give me the best shot at fitting in. In time, being the only non-White kid in school led to being the only non-White partner at a consulting firm.

I used to tell myself that my superpower was being a chameleon, able to blend in with people different from me. It meant I had the skills to work with road maintenance workers in rural Australia and microfinance organizers in Tanzania. It meant I could play the roles needed to connect and have sufficient credibility with corporate executives four decades my senior. It meant I could figure out how to take the feedback that I needed to “be more manlike” when working with the managers of a global insurance company. After all, I knew how to make myself more palatable for other people’s consumption. But along the way, I realized I was losing something in that approach. Me. My own thoughts. My own feelings. My own ideas. My own sense of being.

I’ve spent more than a decade facilitating workshops, giving keynotes, and coaching leaders on skills for negotiating, having difficult conversations, increasing influence, and giving and receiving feedback. All skills essential for leading and working in an increasingly automated and disconnected world. While the theories and practices from my colleagues at the Harvard Negotiation Project are sound, I’ve wondered, Why is it that some people still don’t actually negotiate or have the difficult conversation? Why, despite begging from leadership and HR, the manager still won’t give the feedback and the employee is instead reorg’d or passed on to yet another manager? Why is it that we complain to our friends about the other people in our religious organizations, soccer leagues, and families but don’t talk directly with them? Why is it that we need to edit out parts of ourselves to be accepted?

The answer is the pervasive influence of silence.

Silence we’ve each learned, benefited from, and been rewarded for. We’ve learned when staying silent benefits us. When silence is considered proper or professional. When it gets us the better outcome—or helps us avoid short-term pain. We’re comfortable with silence because it’s familiar. It’s a coping mechanism and a strategy for maintaining order. Silence leads to a known set of results—primarily, our personal short-term safety and well-being. Biting our tongues keeps the peace at the Thanksgiving table—after all, we won’t see them again until next year if we’re lucky, right?

These unconscious patterns around silence drive our day‑to‑day behavior. But without understanding the role silence plays in our lives and how it serves us, we can’t make the conscious decision to choose another way.

Excerpt attached and credit line here: From UNLEARNING SILENCE by Elaine Lin Hering, published by Penguin Life, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Elaine Lin Hering.