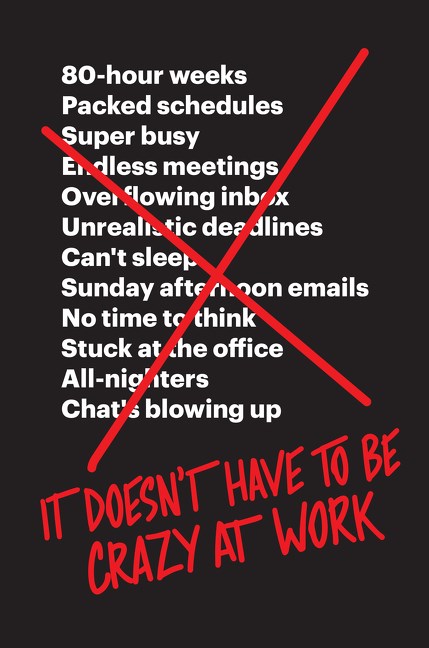

It Doesn't Have to Be Crazy at Work

October 05, 2018

Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson know that it doesn't have to be crazy at work, because they've created a company of calm in the midst of the industry that brought the culture of crazy upon us all.

It Doesn't Have to Be Crazy at Work by Jason Fried & David Heinemeier Hansson, HarperBusiness, 240 pages, Hardcover, October 2018, ISBN 9780062874788

Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson don’t mince words. “If it’s constantly crazy at work,” they write early in their new book, It Doesn't Have to Be Crazy at Work (a title so clear they don’t even have to bother with a subtitle), “we have two words for you: Fuck that.”

Oh, wait: “And two more: Enough already.”

Maybe not the most eloquently stated position, but one which clears away any misconception and immediately grabs your attention. And they have over 200 pages left for a more thorough examination of the “that” which they are… well, that which they believe has been done enough already—too much, even. The craziness at work, that is.

Once they have your attention, they keep it with quick chapters, most two or three pages long, and each packed with a punch that seems both profound and practical—profound for how clear and different they tend to be from most accepted business wisdom, and practical because almost everything they describe is immediately applicable.

Fried and Heinemeier Hansson introduce a brilliant premise at the beginning of the book—viewing their company as a product, insisting: “We work on our company as hard as we work on our products.” The evidence to back that up is abundant in the book, even if much of that work is, in fact, spent on limiting how much they allow work to take over their lives and the lives of all those at Basecamp. Ask almost anyone you know how things are at work, and the answer you’ll invariably get is some variation of “crazy.” Fried and Heinemeier Hansson have made great effort to make sure that’s not the answer at Basecamp, to eschew the crazy for calm. Doing so has led them to break from many traditional, taken-for-granted best practices in business, and to embrace some heretical ones. For instance, they don’t set sales goals at Basecamp. Being endlessly experimental in running their business, they did try it once, figuring “Why not?”

And the answer to “Why not?” became a very clear “Because (1) it’s disingenuous for us to pretend to care about a number we just made up, and (2) because we aren’t willing to make the cultural compromises it’s take to get there.”

Because let’s face it: Goals are fake. Nearly all of them are artificial targets set for the sake of setting targets. These made-up numbers then function as a source of unnecessary stress until they’re either achieved or abandoned. And when that happens, you’re supposed to pick new ones and start stressing again.

Their goal now is to have no goals, and reading that feels like a truth serum. Here’s a question: would your sales numbers actually change one iota if you didn’t set goals? Are your goals informing and improving the work done at your company, or simply increasing the amount of stress and the chance that someone within the company will potentially compromise real values to meet those fake numbers? Think about what setting artificial numbers for new opening accounts did to Wells Fargo—to their reputation, yes, but more insidiously to their culture. Besides, the simple reality is that, as the authors contend: “You don’t need something fake to do something real.”

Here’s another piece of advice antithetical to the Silicon Valley ethos that has seeped into the broader business culture: “Don’t change the world.” And don’t pretend you are because you’re developing an app, or insist others around you work around the clock to meet such a delusional ambition. As the only two C-suite level individuals at the company, they freely offer that:

Basecamp isn’t changing the world. It’s making it easier for companies and teams to communicate and collaborate. That is absolutely worthwhile and it makes for a wonderful business, but we’re not exactly rewriting world history. And that’s okay.

They are keenly aware of their impact on their own workers’ lives, however, and that is a responsibility they focus seriously on. It all begins with protecting their ability to focus on the work they were hired to do, and to do that work in a standard, sensible work week that generations of workers fought for us to have. Reading what they’ve done to ensure that will be uncomfortable at times, because it likely looks nothing like your workplace. Writing of their avoidance of weekly status meetings, and their effect on not only individuals’ time, but on companies’ overall productivity, they write: “Eight people in a room for an hour doesn’t cost one hour, it costs eight hours.” They’ve also eliminated shared work calendars, calling them “one of the most destructive inventions of modern times.” No one at Basecamp can see anyone else’s calendar, or intrude upon them, which makes scheduling meetings harder—by design. “If you can’t be bothered to schedule a meeting without software to do the work,” they write, “just don’t bother at all.” They also operate on a principle of asynchronous rather than real-time communication, and an expectation of eventual rather than immediate response (to coworkers, at least; the expectations for replying to customers is different, and stated clearly—though it has also been experimented with). Writing of the “presence prison” at most workplaces—the need to broadcast what you’re doing and to be available to others at all times—they sound an alarm about the consequences of “chained to the dot—green for available, red for away,” which insinuates “away from work.”

[W]hen everyone knows you’re “available,” it’s an invitation to be interrupted. You might as well have a neon sign flashing BOTHER ME! hanging above your head. Try being “available” for three hours and then trying to be “away” for three hours. Bet you get more work done when you’re marked “away.”

“As a general rule,” in fact, “nobody at Basecamp really knows where anyone else is at any given moment.” Sounds like chaos. Works like a charm. And these aren’t assumptions. These are all things they’ve tried and tested. They’ve found that chat is a great tool, “if used sparingly,” as in an emergency when you need to gather disparate voices quickly, and for “watercooler-like social banter” and “generally building a camaraderie among people during the workday.” But, as a general rule:

Following group chat at work is like being in an all-day meeting with random participants and no agenda.

So, what do they do instead? They have borrowed the idea of office hours from academia, meaning that all subject matter experts at Basecamp publish office hours of when they’ll be able to answer others’ questions about their own area of work and expertise. It might seem inefficient, because you may have to wait a few days for an answer on what seems to be a pressing concern, but we all know that most things can wait, and Fried and Heinemeier Hansson insist most things should—and, in their company, things do. This increases the focus and productivity of experts who are frequently interrupted otherwise. You could say that it literally saves their day.

They don’t eschew the open office concept popular today for the cubicles of yesteryear, but they have instituted “Library Rules” to maintain a calm and quiet atmosphere more conducive to focus and work than today’s open office distraction factories. They have a handful of smaller rooms in the center of the office that act as spaces people can meet to work together at full volume or make a private call. And if you’re skeptical this could work for your company, they offer this suggestion:

Make the first Thursday of every month Library Rules day at the office. We bet your employees will beg for more.

They also don’t offer the office “perks” common at so many other technology companies, like game rooms, free lunch, laundry service, and ample libations, believing they’re designed to blur the line of work and play and keep people at work longer. Not only do they not require anyone physically come to their Chicago headquarters to work (as their website states: “Everyone at Basecamp is free to live and work in the places they thrive, and most of us do just that,” spreading their 54 workers to 32 cities across the world) the benefits they do offer are all focused on getting employees to leave the office and live a more balanced, healthy, and fulfilling life with family and friends outside it. They ended their unlimited vacation policy when they discovered it was actually leading to employees taking less vacation. But, in addition to offering three weeks paid vacation, they also pay for the vacation itself. Their list of perk benefits is as follows:

- Fully paid vacation every year for anyone who’s been with the company for over a year, up to $5,000 per person or family.

- Three day weekends all summer—May through September.

- 30-day-paid sabbaticals every three years.

- $1,000 per year continuing education stipend.

- $2,000 per year charity match.

- A local monthly CSA (community-supported agriculture) share.

- One monthly massage at an actual spa, not the office.

- $100 monthly fitness allowance.

That's right, in one of the most overworked industries, they work only 32 hours a week in the summer, and everything works out just fine—better, even. And that fitness allowance can be used for gym memberships, yoga classes, running shoes—anything their employees are doing on an ongoing basis to lead healthier, physically fitter lives.

They also focus on growing and nurturing their own talent, rather than poaching from others or searching in more typical talent pools. When considering candidates, they actually hire all the finalists for the job for a week, pay them $1500, and have them do a sample project. No brain teasers, riddles, or on-the-spot questions, and they “don’t really care where you went to school, or how many years you’ve been working in the industry, or even that much about where you just worked.” If they did, they’d most likely hire a lot of people from similar backgrounds, of a similar age, race, and gender as has become a problem across tech. They focus on if candidates can do the work, and on hiring new perspectives.

We look for candidates who are interesting and different from the people we already have. We don’t need 50 twentysomething clones in hoodies with all the same cultural references. We do better work, broader work, and more considered work when the team reflects the diversity of our customer base. “Not exactly what we already have” is a quality in itself.

Imagine if the rest of the software industry, and larger tech world, followed suit. Where they adhere more to industry norms is in salary, but they have done away with negotiating salaries, removing an annual process that is stressful for most employees, and requires a skill set that has nothing to do with the actual jobs they hired people to perform. They provide everyone in the same role and same level the same pay, target that pay to the top ten percent of the market rate for that position, and base those rates on San Francisco numbers, the highest paying city in the world for their industry, even though they don’t have a single employee there. They’ve also eliminated bonuses, finding that they were being treated as expected income by employees, while keeping salaries benchmarked against others companies’ salary plus bonus packages. They do have a profit growth-sharing scheme that distributes 25 percent of growth in any given year to employees on an equal share basis, regardless of position or individual performance.

Almost everything they do is contrary to typical of the industry they’re in, and how it has influenced business practices more broadly, started with how they've funded it from the very beginning:

We’re in one of the most competitive industries in the world. In addition to tech giants, the software industry is dominated by startups backed by hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital. We’ve taken zero. Where does our money come from? Customers.

They’ve never had to consider burn rates. They turned a profit in their first year in business, in 1999, and have done so every year since.

When companies talk about burn rates, two things are burning: money and people. One you’re burning up, one you’re burning out.

They’ve also avoided the per-seat pricing model most software companies rely on from the beginning. Basecamp is going to cost you $99 a month, whether you have five people using it or 5,000. That sounds crazy, like it’s potentially leaving a lot of money on the table. But they value their freedom more—able to make decisions and software for “a broad base of customers, not at the behest of any single one or a privileged few,” free from the pressure to chase big contracts and the larger risk that reliance on them entails, and dedicated to a focus on small businesses like their own. Rather than focus on differentiating their products, they have narrowed what they offer to just one. And they made that decision to cut back what they offer not when times were lean, but when business “had never been better.” They simply made a conscious decision to focus on what they knew to be their best product, and the way they wanted to work. Did they turn down an opportunity for greater and quicker growth doing so? Almost certainly. But…

Whatever the pressures, there’s no law of nature dictating that businesses must grow quickly and endlessly. There’s only a bunch of business-axiom baloney like “If you’re not growing, you’re dying.” Says who?

Well for one, usually a company's investors, impatient for outsized returns on their investment, but we’ve already told you that Basecamp has avoided that trap. And that decision has helped them avoid another trap:

As we continued to hear fellow entrepreneurs reminiscing about the good old days, the more we kept thinking, “Why didn’t they just grow slower and stay closer to the size they enjoyed the most?” … We decided that if the good old days were so good, we’d do our best to simply settle there. Maintain a sustainable, manageable, size. We’d still grow, but slowly and in control. We’d stay in the good days, no need to call them old anymore.

“Set out to do good work,” they write, “Set out to be fair in your dealings with customers, employees, and reality.” In a world of gone crazy, that sounds reasonable.