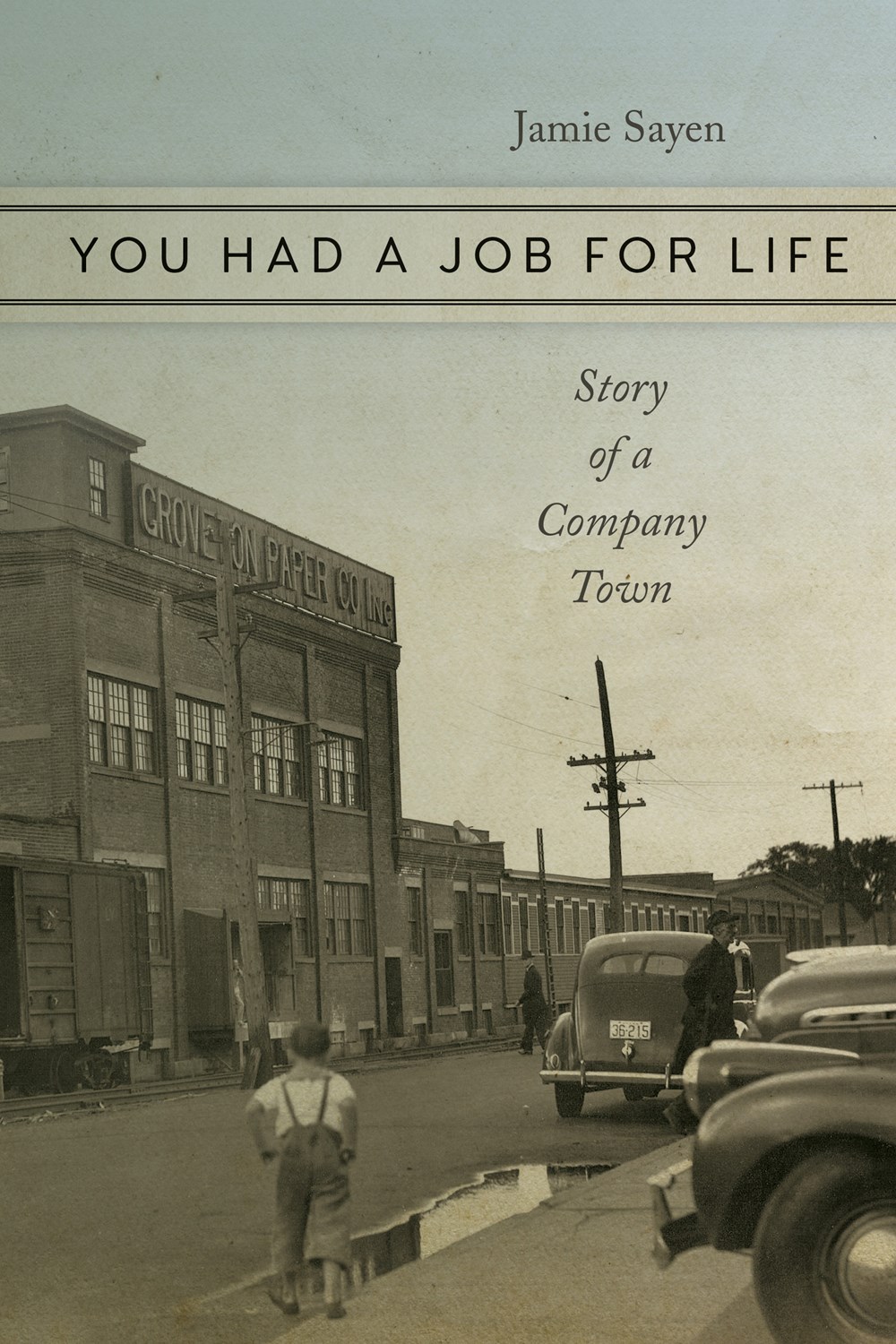

You Had a Job for Life: Story of a Company Town

December 22, 2017

Jamie Sayen tells the story of Groveton, New Hampshire, and the mill that was once the life of the community, in the residents' own words.

You Had a Job for Life: Story of a Company Town by Jamie Sayen, University Press of New England, 304 pages, Paperback, December 2017, ISBN 9781512601398

The story of Groveton, like the story of Janesville, is the story of America. Groveton grew up, as so many American towns have, around a single employer during a period of industrial expansion. In Groveton’s case, it was a paper mill that dates back to 1891, and the industrial boom that occurred in America following the Civil War.

Jamie Sayen was drawn to this history, and began gathering stories for the Groveton Mill Oral History Project in 2009 as an assignment in a graduate ethnography course. It ended up being a life-altering experience:

I soon realized I was the willing captive of a far greater project. By the summer of 2013 I had accumulated over one hundred hours of taped interviews with fifty-six individuals who had worked at the mill or grown up in Groveton.

“The transcripts of these interviews,” he tells us, “fill more than two thousand pages.” Those original transcripts, along with the audio of the interviews, now reside in multiple libraries in New Hampshire. To share those stories with the wider world, Sayen has written You Had a Job for Life: Story of a Company Town. The story is set to the rhythms of the life of the mill, which as resident Hadley Platt and so many others put it, was “the life of this town.” The whistles that emanated from it dictated the pace at which life moved, signaled when it was time to get lunch or go home for the night at 9 o’clock curfew—before the sulfur smell from the acid towers at the mill descended upon town. This is, you may have guessed by now, a story entirely in the past-tense, as the mill’s hundred-year-old “Number 3” paper machine was shut down on December 20, 2007, almost a decade ago to the day and just days before Christmas. One former employee who grew up around the mill in Groveton, and who went in to witness the last run of that historic press, said of that moment:

A sad day. You figure all those people—just throwed out, done; that’s it. They all gotta go find jobs. I feel so damn bad for all those…

But the life and livelihood the mill provided was never easy. Paper manufacturing is a smelly, chemical-befouled process. Most workers lived in company houses, and on company script. And it made the entire town, as another resident put it, “the armpit of the north country,” “stinky, smelly, and dirty.” It was damned hard, dangerous, and dirty work, and it was known for much of its early history for being poorly run. Things improved after the mill was purchased by James Campbell Wemyss Sr. in 1940, and the factory doubled in size in the decades of postwar prosperity after WWII. It was eventually passed down to his son Jim Jr., or “Young Jim,” who was seriously wounded in the final months of that war in France (Eighteen Groveton soldiers paid the ultimate price in the war), and would remain at the helm of the company for decades after returning from it.

Because it stems from the oral history of the residents, You Had a Job for Life is a deeply social history. You’ll learn everything you ever wanted to know about paper manufacturing, and you’ll learn it from the mouths of the people who owned the mill and worked it every day. The history of the community is told in the voices of the people who have lived, and still live there. But the stories, of work on the rivers pulling logs into the mill, or in the heat and noise of the mill itself, of lost limbs and lives, and of kids growing up around it all, are also the stuff American industrial history and mythology are made of. So it all reads like a New England version of The Jungle, or the early industrial poems of Carl Sandburg, with Tom Sawyer and a bit of Horatio Alger Jr. thrown in. It includes labor disputes and the women’s struggle for equal pay, the financial machinations that passed ownership through multiple hands over its century in operation, and the bare hands of workers building it all from the ground up. It is all so vivid you can almost smell the sulfur on their skins.

Lyse Perkins was forced to take a job at the mill after an accident there left her husband unable to work. She would go on to fight for women’s rights and equal pay. We first meet Pete Cardin as “a skinny little kid” on the crew pulling pulpwood out of the river onto the conveyor belt into the mill before being shipped out to Vietnam. Cardin returned to the mill after three years in the Army, eventually becoming production manager of the entire operation. He is the man who eventually “orchestrated what he termed a ‘clean shutdown’” of the Groveton Paper Board that would prove to be the ultimate death of the mill. Ironically, some of the equipment would be sent across the world to the country of Vietnam, where he once served. He was not the only one:

Many of the mill workers served in the nation’s military in times of war and peace. At the mill, they endured stressful, dangerous working conditions, morning, afternoon, and night. When the mill was struggling to survive, they did everything asked of them to keep the mill running.

The mill’s last superintendent, Groveton native Dave Atkinson, attests to that hard work and sacrifice, and the near miracle the workers accomplished in cutting costs and controlling the things that were within their control. But world events and economic forces intervened. The overthrow of the Shah of Iran and the rising fuel costs that resulted crippled a larger company Groveton had merged with in the late ’60s, and a hostile takeover by Sir James Goldsmith was not far behind that. Wausau Paper Mills Company, based here in Wisconsin, came to its rescue just before it was about to be shut down, and the mill saw some of its best years with an inflow of investment from the company, but it was Wausau that would ultimately sign its death warrant by placing a covenant upon future owners from making paper there when it left.

It is, unfortunately, not an unfamiliar story.

The litany of uncontrollables that doomed the Groveton mill is familiar to rural and urban communities throughout the United Stated that have lost an auto plant, or a steel, textile, or paper mill: absentee owners with scant commitment to the local community; declining investment in modernizing the aging machinery and infrastructure; soaring energy prices coupled with stagnant or declining commodity prices; and competition from mills and factories located in other regions of the United States or in foreign countries where wages are lower and environmental protections are lax to nonexistent.

And because of the nature of corporate accounting and the calendar year, it is unfortunately a story that too often takes place just before Christmas. As mentioned above, the Groveton mill shut down for good on December 20, 2007. The GM plant at the heart of the story in Janesville closed for good two days before Christmas in 2008. There is a reason that the hellscape the 45th president depicted America as in his inaugural address at the beginning of this year rings true to so many. But the Christmas gift he’s delivering America this year is a tax bill that, according to the Tax Policy Center, gives 83 percent of its tax cuts to the top one percent, those that make the managerial and political decisions that propel the forces at work on small towns like Groveton.

You Had a Job for Life is the story of a small town struggling to survive, even in the best of times when everyone seemed to have a job for life. It is the story of a mill born out of a Civil War, that boomed in the aftermath of a World War, and that vanished in the midst of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the financial crisis of 2007. But, while world events, energy prices, and American history are all larger forces at play, this is ultimately the story of those that lived through it all in Groveton, New Hampshire, from the family of industrialists that owned the mill for close to 50 years, to all those who helped build it from the ground up and were left behind as it was literally torn down.

Jamie Sayen, in a postscript to You Had a Job for Life, offers what I find is a more sustainable and positive vision of the future, one that takes into account both the economic and ecological needs of people in communities like Groveton. Because, though the jacket copy states that the book is "a heartbreaking story of the decimation of industrial America," I found it to also be the heartbreaking story of industrial America. We are reminded that, even in the days the mill provided jobs for life, it was also fundamentally detrimental to the health of the people who lived their life there—and to the planet. And, it seems to me that, as we are enter a new year, we should make a resolution to build businesses that better serve both.