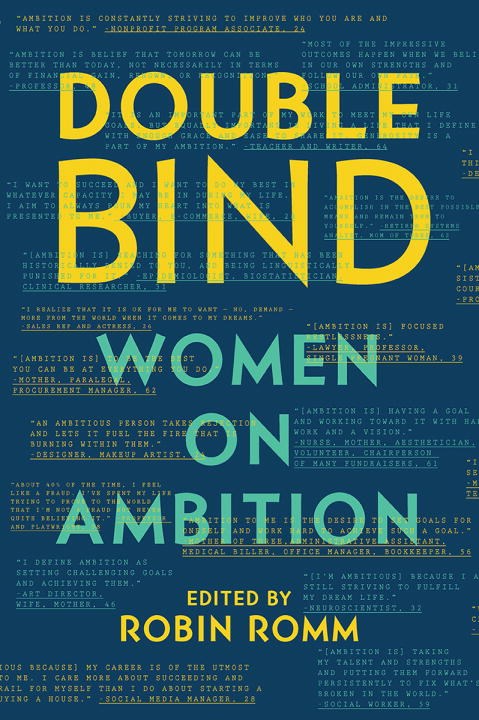

Double Bind: Women on Ambition

May 16, 2017

Robin Romm has edited a book of essays from successful women that takes on "the last feminist taboo"—ambition.

From the paperwork I received after paying a $60 information release fee to Lutheran Social Service of Minnesota, I learned that if my biological mother had not given me up for adoption, I would have grown up on the west side of the state in a family of 6 among women who sewed.

I don’t mean to say I truly know anything about those women. I can imagine my birth mother filling out a section of a form that read, HOBBIES and INTERESTS, and sewing came to mind. Still, when I read, and reread, the lengthy synopsis of my biological family’s life, the descriptions of my birth mother, her siblings, her parents, I look for myself. “Skilled at sewing,” is reported several times. Of course I wonder if I am like them. If they are like me. If my love of writing and reading is somehow rooted in the same inclinations for quiet labor as sewing.

While I’ve never been particularly bothered about being adopted, I had certainly concocted fantasies. I’d been told early on that my birth mother was a high school student and that I was premature; this led me to all kinds of exotic wonderings about drugs, about scandal. But from the report, it appears my alleged father was in the military, and my birth mother had ambitions to become a nurse. When I read that, I understood. She had made a choice to pursue her work, and in that decision, I saw myself.

I searched for myself as well in the essays included in Double Bind: Women on Ambition by Robin Romm. Funny, sharp, sometimes conflicted by the subject matter, but always engaged with it, the women who wrote essays for Double Bind tell their stories with bravado. I gulped my way through it like a kid who suddenly remembers he’s thirsty. I didn’t know I needed this book of essays—”a striking book about struggle and failure and achievement and identity and everything in between” writes editor Robin Romm—until I started reading, and then I couldn’t stop.

Pam Houston has no trouble with her ambition. In her essay, “Ebenezer Laughs Back: Confessions of a Workaholic,” she proudly slaps on a badge for her workaholism like a 2016 Democrat with an “I Voted” sticker. Work is her salvation; and I too understand the succor found in work. Work is something that can always be done, while life is something that is constantly threatening to be undone. She is the author of five books, and, she proudly tells you, of her life.

I have come to understand that ambition’s real payoff is less about being loved for the work you do and more about getting to do the work you love.

Camas Davis pulled the plug on a career as a magazine editor, searching, rather blindly by her account, for a career that enabled her to “do” instead of tell readers what other people do. To say she became a butcher is to underplay the significance of her new endeavor. She became a famous butcher due to a confluence of events: one being the popularity of farm-to-table dining that compelled a popular knife company to use innovative chefs to shill their product. Camas became the “Poet Butcher” in those ads and brought national attention to her ambitions, but “Girl with Knife” explains why she was suspicious of all the notoriety.

I couldn’t shake the feeling that the spectacle of my gender, of my particular choice to study butchery, was the reason I was getting the attention, not my actual skill (or even my imagined skill).

The essays in Double Bind, which aim toward examining how internally complex ambition is for women in particular, aren’t all so celebratory. Robin Romm, the editor of this collection, tells a story in “Reply All” which features a more external foe. An accomplished writer and teacher, Romm decided to become a parent, but getting pregnant was a far less easy and far more consuming—time, money, focus—endeavor than she’d have ever estimated. Her essay opens with the happy announcement that she is going to have a baby, but then spools out the difficult decisions she had to make with regard to a career opportunity and the sexism she faced when trying to mediate a solution that served both her as a mother and the college that wanted to hire her. The man who initially championed her hiring pulled his recommendation in response to her request for a modified schedule (her effort to stay true to her ambition while protecting the opportunity to be a present mother), revealing his concern about her capabilities not by speaking to her personally but by accidentally including her via “reply all.”

It was so nice of him to help me see my limits, wasn’t it? It’s great when men do that.

It’s no surprise this book of essays features the writing of many successful authors and essayists; these are the women who are comfortable digging into the ambiguities of a concept and then writing about what their excavations reveal. The addition of a butcher, a dogsledder, and a lawyer builds out the collection, but the overall feel of the book—despite the many slightly derisive references to “leaning in” found throughout—is more academic than self-development. As Romm states in her introduction, you won’t find advice here, but you will find stories. And the most effective of them get to the heart of just how foreign owning their ambition can be for women, especially those who have not come from a family history of owning the path of one’s own life. Such as Ayana Mathis.

Ayana Mathis wrote a book. It was her first book. That book became an Oprah’s book club bestseller overnight. But that kind of success was something Mathis was completely unprepared for because no one in her family had ever experienced even a modicum of such success. Her essay, “On Impractical Urges,” first tells how this fortune befell her, and seeks to unveil how fortune has failed her. “I come from strugglers. For us, the measure of a life is survival by means of elegant improvisation and wiliness; grace and dignity in the face of difficulty.” Her success enabled her to become the first in her family to own property, but in that house, she still struggles to find the version of herself who wrote that book and who can write another one:

The new self and I marched through the alien landscape of our new life. I was unmoored, I was ashamed of my good fortune. I felt I was a fraud and poseur, as though by some bizarre trick of the universe I had gotten something I shouldn’t have had.

After reading Elisa Albert’s essay, “The Snarling Girl: Notes on Ambition,” I wondered what would happen if you invited both Albert and Ayana Mathis to dinner and let them sort this ambition thing out together. Albert, also a writer, comes from a very different background than Mathis—“rich bitch west LA and Hebrew school and Zionist summer camp”—and I suspect that dinner would be an awkward one because rather than earnest struggle, her spiky voice is one of been-there, done-that cynicism. She works toward discrediting the very word “ambition” instead of making peace with it: “I’m unavailable for striving today. I’m suuuuuper busy.” What can be read as entertaining but privileged machismo (what is the female equivalent?!?) is really a useful self-correction for all of us who get confused at the intersection of work and achievement.

Recognition has nothing to do with the work, get it? The work is the endeavor. The work is the process. Recognition comes, if/when it does, for work that is already done, work that is over. Recognition can really f**k you up.

Robin Romm describes Double Bind as “a validation that women’s ambition is tricky to navigate but entirely worthwhile, and that no young woman should feel, as I did, confused and silenced by all that is unspoken about it.” The essays I mention above, and more by notable voices like Roxane Gay, Claire Vaye Watkins, and Molly Ringwald, each offer a look at what drives us, and what ultimately comes home to roost once success has been achieved. Truly a double bind.

I have no way of knowing whether my birth mother was so driven to have a career that she gave me up for adoption. Maybe it’s just another fantasy that fits better with my current chosen narrative. But if she did, I’m proud of her, and I think she’d be proud of me for the work I do and the choices I’ve made, even if those choices cause me both joy and regret. After all, that’s the thing with choices. But, if we lead with our ambition, at least we know we are in the lead.