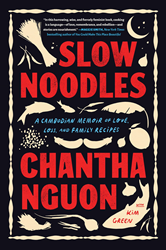

Slow Noodles: A Cambodian Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Recipes

March 28, 2024

Slow Noodles is a powerful memoir that illustrates how food can preserve a Cambodian refugee's connection to her past and inspire hope for a better future.

Slow Noodles: A Cambodian Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Recipes by Chantha Nguon, Algonquin Books

Slow Noodles: A Cambodian Memoir of Love, Loss, and Family Recipes by Chantha Nguon, Algonquin Books

Food is far more than sustenance. Food can be deeply personal, bringing together people and communities, both in good times and in bad. It can serve as a cultural symbol; national dishes represent entire countries and cultures, made tangible by cooking, serving, and eating. Food is a conversation starter, a way to check in on friends: Have you eaten today? And with our senses of taste and smell being so closely linked to memory, food can be a fast track to access emotions wrapped up in dishes we experience throughout our life. At the most basic level, food keeps us going, but as societies, we’ve developed intricate cuisines and customs, allowing it to mean so much more.

Food is the thread of Chantha Nguon’s memoir, Slow Noodles, written with Kim Green. In it, Nguon details her life as a Cambodian refugee. Initially, she flees with some of her family from Cambodia to Vietnam to escape persecution and violence under the dictator Pol Pot. She later travels to Thailand and lives in refugee camps for decades, before finally settling again in her homeland. Nguon loses much of her family, eventually finding herself completely alone by her mid-twenties. Along the way, she survives by the skin of her teeth, serving drinks in cafes, cooking for brothels, selling street food, and working as a suture nurse, eventually creating a stable life in Cambodia for herself and her family.

Every time Nguon writes about a new place, she starts with the food: what people ate when they had everything and nothing, what people cooked in street market stalls, how people managed to survive with fatally underfilling rations in refugee camps. She fondly remembers her childhood in her mother’s kitchen and pays homage to her recipes after years of struggle. Armed with her memory and a strong nose, she recreates more than twenty recipes from both childhood and adulthood, with Cambodian, Vietnamese, and Thai influences.

These recipes are written step-by-step, with extensive notes on ingredients, techniques, and supplies at the end of the book, and additional photos and videos related to these recipes online. My copy of Slow Noodles is not shelved with the memoirs in my bookcase, but rather with my cookbooks in my kitchen, next to my oils and spices. Many of these recipes can be recreated in your kitchen, while others may require hours or days of prep; Mak and Clara’s Stir-Fried Egg Noodles, noted as a good recipe for beginners, is one of the first I intend to make. Then there are recipes that, if you are lucky, you will never have to make, like the Rice Bowl of Forgetting: the plain rice Nguon ate after her mother passed in Saigon, Vietnam, cooked using wooden clogs as fuel and flavored only with cheap fish sauce.

In the case of Slow Noodles, food is also a metaphor. Nguon writes about her mother’s way of thinking: when cooking, spending the time to roll out noodles individually is essential, and taking shortcuts can ruin the entire dish. This “slow noodles” philosophy goes beyond the kitchen: Nguon considers Cambodia’s future as a country devastated by genocide and war, a people traumatized and deeply mistrusting of one another. How does one begin to rebuild after mass violence and incredible loss? Slowly, with deep love and commitment.

Nguon lives this philosophy to this day. In 2001, living in Stung Treng, Cambodia, she cofounded the Stung Treng Women’s Development Center (SWDC), which aims to give the women living in and around rural Stung Treng opportunities for education and economic advancement, both for themselves and their children. At a local level, she builds trust and community with women and families to reconstruct Cambodia from Year Zero (1975, the year Pol Pot ordered the destruction of Cambodian culture to reset society).

In Cambodia, restrictive norms surrounding the roles of men and women had permeated for years largely unquestioned; women were expected to be demure and serve their husbands, and while eldest sons inherited family wealth and land, eldest daughters inherited the labor of taking care of their parents and siblings. These ideas proved entirely unhelpful for the women who survived Pol Pot and left them vulnerable to abusive husbands and exploitation at every turn.

Nguon criticizes antiquated roles for men and women, noting that she frequently broke these social rules to survive and couldn’t afford to rely on a man to provide for her. She raised her daughter Clara to resist these norms as well, taking care to give her the education typically reserved for sons to ensure she could stand on her own two feet. Nguon preserves aspects of Cambodian culture in her recipes while still confronting aspects of society that keep women from leading stable lives.

In Slow Noodles, Nguon uses food as a guide to create a deeply moving testament to human strength, love, and resistance. This book serves an important purpose: to prevent the past from being buried. Because we use the past to understand the present, it is vitally important that this history not be covered up. Rather, this story must be told, even if the subject at hand is overwhelming and difficult to comprehend. By reading Nguon’s memoir and even recreating one of the dishes within, you can take on an active role in ensuring that this history will not be forgotten.