Unreasonable Hospitality | The Lost Chapter

March 01, 2024

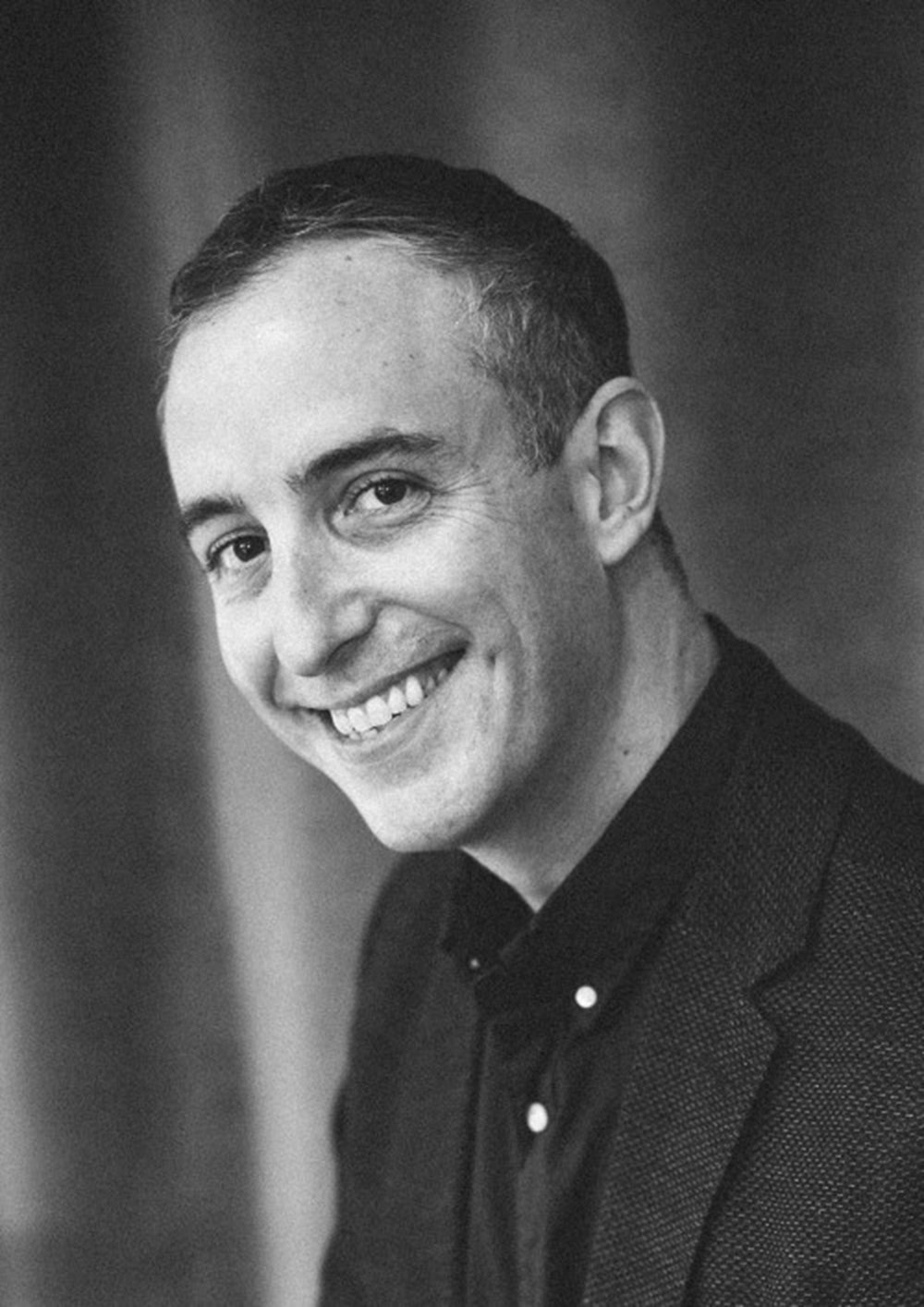

In Unreasonable Hospitality, Will Guidara chronicles the lessons in service and leadership he has learned over the course of his career in restaurants. There was one lesson, however—in a "lost chapter"—that didn't end up making it in the final cut of the book.

If you’ve ever written a book, you know that right before it goes off to press, you take one final pass at every single page—one last edit to make sure that it’s exactly the book you want it to be… that it’s fully ready for the world. I got lucky and had the chance to do Unreasonable Hospitality’s final edit alongside Simon Sinek, who I now believe is one of the world’s greatest editors. He actually might be too good—since quite a few parts of the book ended up on the cutting room floor at the end of our day together.

If you’ve ever written a book, you know that right before it goes off to press, you take one final pass at every single page—one last edit to make sure that it’s exactly the book you want it to be… that it’s fully ready for the world. I got lucky and had the chance to do Unreasonable Hospitality’s final edit alongside Simon Sinek, who I now believe is one of the world’s greatest editors. He actually might be too good—since quite a few parts of the book ended up on the cutting room floor at the end of our day together.

While I loved some of the lessons and ideas in these parts, the cuts needed to happen—they were just slowing the book down too much. It was important to me to write a quick read; something that gripped you the whole way through—that you could easily reference once you were finished. But this chapter was one I liked too much to simply let it disappear and never see the light of day—hence its release to you now.

So, I’m proud to share this lost chapter called “Whatever it Takes”—about brand collaboration, learning lessons from unlikely places, and doing whatever it takes to bring the most fully realized version of an idea to life.

◊◊◊◊◊

UNREASONABLE HOSPITALITY

THE LOST CHAPTER

WHATEVER IT TAKES

In 2011, after Eleven Madison Park: The Cookbook was published, our team hit the road and traveled across America to do a series of events celebrating its release.

Our first stop was in Chicago, where we threw an epic party with Alinea owners Grant Achatz and Nick Kokonas at their restaurant Next, and at Aviary, the bar they own right next door.

We had a blast. Grant is a genius and an artist and, like me, he’d grown up in restaurants. Nick is a brilliant businessperson. He was the first person in the country to realize that because restaurants are an experience, like attending a concert or a night at the theater, tickets can be sold to them in the same way. He would go on to develop a ticketing system called Tock, which changed the game for restaurants by collecting money in advance and dramatically reducing no-shows.

So we had lots to talk about when we went out for a nightcap after the event, and it’s possible that we drank a few too many cocktails, because when I suggested swapping restaurants for a week, everyone thought that was a great idea.

A week later, when I was back in New York, I found the reminder email I’d sent to myself and wondered: Is this a cowboy hat?

You know when a person goes on vacation and buys a cowboy hat? Then they get back home, where nobody is wearing a cowboy hat, and realize their new hat looks completely ridiculous. A cowboy hat idea is one that seems inspired when you have it, but fails to stand up to the cold, harsh light of day. (Both cowboy hat purchases and cowboy hat ideas often have their genesis in a bar, I’ve noticed.)

Sometimes, though, you turn out to be the rare person who can wear the hell out of a cowboy hat. And sometimes, after the Alka-Seltzer, you discover that the wacky idea you had was actually a good one.

The difference between good organizations and great ones is not the caliber of the ideas, but whether people are empowered to act on them. It’s easy to talk yourself and the people you work with out of pursuing a wild notion: “It’s going to be too hard to execute that,” or, “How on earth are we going to pay for it?”

Those are terrible lost opportunities. So any time I get an idea, whether in the middle of service or during a night out, I send myself an email. If I forget it, as I am likely to do when I’m busy, it dies immediately. Then I force myself to follow up, as I did with Grant and Nick. Maybe swapping restaurants was a cowboy hat idea, or maybe it was an inspired one, but the only way we were going to find out was by getting into the nitty-gritty and discussing it.

Luckily, they didn’t think it was too crazy. Or maybe they were just crazy enough to agree to it, because in the fall of 2012, Grant and Nick loaded a forty-five-foot U-Haul with appliances and custom plates and artwork, and drove it eight hundred miles to Eleven Madison Park.

A month later, we packed a U-Haul with our own custom plates and artwork, gueridons and glass cloches—even a bar, since Alinea doesn’t have one. If we were going to take Eleven Madison Park to Chicago, then it needed to feel like Eleven Madison Park.

We called the exchange the 21st Century Limited, after the train that used to travel between New York and Chicago.

Brand Collaborations Can Enhance Your Culture

When companies contemplate collaborating with other companies, it’s usually with brand in mind. Think LEGO x Adidas, Milk Bar x Glossier, Nike x Sharpie. Collaboration is a great way to enhance (and perhaps change) how the public thinks about you.

That’s important. But these collaborations are also a fantastic way to enhance your own culture.

We were already believers in sending our people to learn from other restaurants. Whenever possible, we sent senior managers to eat at or to work a short stage at the great restaurants we had good relationships with—Le Bernardin, The French Laundry, Daniel.

But the 21st Century Limited showed us how powerful it was to collaborate as a collective.

Our catchphrase at EMP was “Make it nice.” The Alinea crew’s catchphrase was “Whatever it takes.” And I got an up close and personal look at Grant’s creative process—which happened to be the origin of that catchphrase—when we sat down and started to talk about ideas for the collaboration.

He had an idea to cover a service piece with autumn leaves, for a course he was going to call A Walk in the Forest.

“That’s going to be really cool,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said. “But how do we make it better?”

We talked about covering the whole table with leaves and I got excited again: “That’s amazing! It’ll be beautiful.”

“Yeah, it will.” Then, a moment later: “But how can we make it better?”

It went on like that, every idea more outrageous and difficult to execute than the one before, until Grant was almost satisfied: “We should cover the whole floor with leaves, so walking to your table is like taking a hike through a forest in upstate New York in the first week of November, kicking through crunchy piles of fall foliage. . . .”

To which I said: “That is fantastic—but where are we going to get enough leaves to cover the floor of Eleven Madison Park?”

He shrugged. “Whatever it takes.”

Ultimately, we shipped in hay bales and hundreds of pounds of oak and maple leaves from Michigan to cover the floor, and warmed cinnamon sticks on top of votive candles near the door. Cooks took private lessons with the painter Thomas Masters so they could create one-of-a-kind works of art—acrylic on canvas, to match the palette of a particular course—that would be lying in wait for the guest under the tablecloth, which we removed halfway through the meal.

That, apparently, was what it took.

The collaboration was amazing for our guests—and for the team. In a lot of cases, employee turnover happens because people are curious and want to learn how other businesses work. An immersive collaboration can scratch that itch by allowing your team to immerse themselves in a competitive organization without having to leave yours.

By the time both exchanges had ended, Grant’s team was saying, “Make it nice.” And for years afterward, I would hear my own team telling one another, “Let’s do it. Whatever it takes.”

"The Lost Chapter” originally appeared in Will Guidara’s Pre-Meal Newsletter. You can find it at unreasonablehospitality.com and on LinkedIn.